[ad_1]

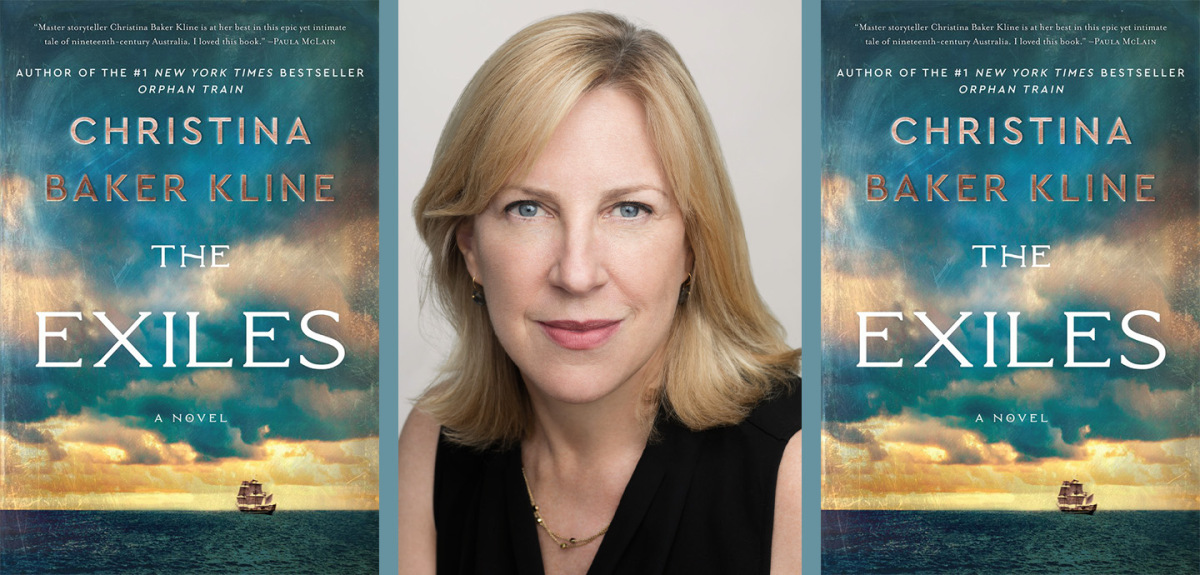

With starred reviews from Library Journal and Kirkus, a TV deal with Bruna Papandrea’s Made Up Stories already inked, and places on a half-dozen lists of the year’s most anticipated books, Christina Baker Kline’s new novel The Exiles is poised to make a splash. It is in some ways a quiet book, focusing on the innermost thoughts and feelings of its main characters—but it’s also epic in scope, addressing matters of life and death, choices and consequences, and the founding of a new nation. These disparate elements combine to make it her best work yet. I talked with Christina about inspiration decades in the making, the responsibility she felt toward those who lived the history she fictionalizes, and the upsides of swapping a virtual book tour for the traditional traveling version.

Greer Macallister

The Exiles is a very different kind of “settler story,” isn’t it? So often, history focuses on simplified stories of “brave” men who forge into what they consider a frontier to build a new country. But you’re casting a more critical eye on Australian history, looking not just at the role of women in this founding, but also the mistreatment of the Aboriginal people who were removed to make way for those settlers. What was the first spark that kindled your inspiration for this book?

Christina Baker Kline

When I was a grad student in my twenties, I read Robert Hughes’ epic history of Australia, The Fatal Shore. The stories that interested me most—those of the convict women essentially transported from Britain as breeders and the Aboriginal people whose way of life was destroyed when colonists landed on their shores—were relegated to only one chapter of that 688-page book, “Bunters, Mollies and Sable Brethren.” Several months later I was awarded a six-week Rotary Foundation fellowship to Australia, where I asked lots of questions about the country’s fraught and complicated past—questions that weren’t particularly welcome. The truth is, as you say, what we call “history” is almost always told from the perspective of the conquerors, a group that has typically excluded women, the poor, indigenous people, and any combination thereof. When I returned to the U.S. I wrote a nonfiction book with my mother, The Conversation Begins: Mothers and Daughters Talk about Living Feminism, and taught memoir writing in a women’s prison; both of these experiences shaped my interests as a novelist. One day, about four years ago, I read a short article in the New York Times about convict women and children transported to Australia. All of a sudden, the bits and pieces of my own experience, predilections, and obsessions fell into place and I knew I’d found the subject of my next novel.

Greer Macallister

How did the research process for The Exiles compare to that of your previous books? Was it harder to dive deep into Australian history than American history, and did the time period of the 1840s present any particular challenges?

Christina Baker Kline

Each novel I write is the hardest book I’ve ever written, which is exasperating. I trick myself into a new book project by assuring myself that this one will write itself, but so far that hasn’t happened. I keep setting myself steeper challenges. My early novels were mostly set in the present, but when I learned that I had a family (in-law) connection to the orphan trains, I held my breath and leapt into the very deep waters of research-heavy fiction. Orphan Train tells the story of destitute immigrant children in East Coast cities who were sent thousands of miles away to be farm labor in the early 20th century; A Piece of the World is about a real-life disabled woman who lived in rural Maine during that same time period and achieved immortality in a painting. In The Exiles, desperate women on the lowest rungs of Britain’s social ladder are exiled to “the land beyond the seas,” as the British courts called Australia, for what was essentially a life sentence; very few returned to their homeland.

While researching The Exiles I visited the People’s Palace and Winter Gardens in Glasgow, Newgate Prison in London, and the English village of Tunbridge Wells; I went to Australia twice and explored the Cascades Female Factory in Tasmania (now a museum), the Tasmanian Museum & Art Gallery, a manor house called Runnymede, the Hobart Convict Penitentiary, the Richmond Gaol Historic Site, the Maritime Museum of Tasmania, and many other convict sites, museums, and libraries in Sydney and Melbourne. I read dozens of books, articles, and essays about convict life and Tasmanian Aboriginal history. To get a sense of the vocabulary and attitudes of the time, I read novels, nonfiction books, newspapers, and journals written in the mid-19th century. (Many of these are listed on my website, if you want to learn more.) I became obsessed with arcane details, some of which I discovered after finishing a draft or two. For example, after I’d handed in the manuscript I read about the inexpensive tallow made of animal fat used for candles in prisons and the homes of the poor. It smelled terrible and dripped copiously. I went back and wove that detail in.

I felt a particular responsibility, while writing The Exiles, to be as accurate as possible. Like the convict women, I am British-born and raised (and have dual citizenship), but I have never lived in Australia and am not an indigenous person. I worked hard to get the details right and convey the nuance of my characters’ disparate experiences. Life was undoubtedly arduous for the convict women, but with luck and perseverance many of them ultimately earned their freedom. This was not the case for the Aboriginal people who were persecuted by the British. While writing the book I consulted and shared my manuscript with experts on these topics, including Alison Alexander, a retired professor who has written or edited 33 books on Australian history and is herself descended from convicts, and Dr. Gregory Lehman, Pro Vice-Chancellor of Aboriginal Leadership at the University of Tasmania and a descendant of the Trawulwuy people.

Greer Macallister

When you were on tour for A Piece of the World, I distinctly remember the amazing slideshow you presented on Christina Olson, the subject of Andrew Wyeth’s classic painting “Christina’s World.” For The Exiles, you’ve got an impressive virtual tour coming up, appearing in conversation with everyone from Amor Towles to Ann Patchett. Do you feel more constrained or less constrained by touring virtually instead of physically?

Christina Baker Kline

I will miss meeting people on the road and hearing their reactions to a novel I’ve spent years writing in solitude. Those interactions are the best part of being on tour. (Snarfing cold breakfast sandwiches in airports, not so much!) This new virtual format presents all kinds of challenges; it’s never been done before on this scale, there can be technical snafus, lighting and sound can be wonky. But anyone in the world can now attend my events and I don’t have to bounce around on trains, planes, and automobiles for weeks on end. I can wear flip flops and shorts in the comfort of my own home without worrying about time zones and jet lag and delayed or cancelled flights. Best of all, writers I admire from across the United States, from an island in Seattle to a horse farm in Virginia, can join me in conversation. I’m really looking forward to it.

I created a slideshow for The Exiles and plan to present it in person someday. It tells the story behind the book: how I came to the topic, where the research led me, and what surprises I encountered as I went along. (In addition to historical photographs, paintings, and maps, I included a few embarrassing photos from my days as a Rotary Fellow touring frozen food factories and timber preserves. Good times!)

Greer Macallister

Definitely sounds like a slideshow worth seeing! Your earlier work was contemporary, but your most recent books—Orphan Train, A Piece of the World, and The Exiles—have all drawn inspiration from real-life people and events in history. When I talked to Therese Anne Fowler, who made a similar move from contemporary to historical, about her future writing plans, she said, “I have wide-ranging interests, and while I might be said to return to a handful of favorite themes in my novels, I’m choosing to write stories that grab me irrespective of their time settings.” Do you also have plans to return to contemporary settings if the spirit moves you, or does historical fiction feel like the right place for you for the foreseeable future?

Christina Baker Kline

I, too, prefer not to be pigeonholed. I don’t even like to be called a “historical novelist” (which is largely a female ghetto, I believe—I’ve written about that here). After finishing each of my recent novels set in the past I was determined to write a contemporary novel, but I kept stumbling on nuggets of history too interesting to ignore.

While I was writing The Exiles, a cousin interested in genealogy reminded me of a family story that took place in rural North Carolina at the time of the Civil War. Alas, I knew instantly that this story was too good to pass up.

Greer Macallister

I can’t resist asking about the recently announced TV adaptation of The Exiles, on which you’ll be working with Bruna Papandrea’s Made Up Stories. It seems like a perfect match, given the Australian subject matter and the company’s focus on telling women’s stories with women in front of and behind the camera. Why does TV feel like the right fit for this story in particular? Is this your first time overseeing the adaptation of one of your books as Executive Producer?

Christina Baker Kline

Congratulations to you, too, Greer: it’s wonderful that Made Up Stories is producing your novel Woman 99! This female-run company seems like the perfect place for both of us. Though I’m not interested in adapting my books myself—screenwriting is such a different beast—I do have lots of opinions and look forward to being involved. With Orphan Train and A Piece of the World (both of which have been optioned for film and are in various stages of development, though you never know, with Hollywood, how things will pan out), I edited the scripts and offered suggestions, but this is the first time I’ll be overseeing the adaptation of one of my books. The Exiles is a pretty dramatic saga and I think it will make a compelling television series, but more importantly, it’ll reach a wider audience than my book, introducing people to a significant piece of history that many know little about. I can’t wait to get going.

FICTION

The Exiles

By Christina Baker Kline

Custom House

Published August 25, 2020

[ad_2]

Source link