[ad_1]

Why did I choose to set my Victorian romance novel against the backdrop of the suffrage movement? I honestly didn’t see how I couldn’t include it. English Common Law decreed that until 1882, a woman’s legal rights were subsumed by her husband’s on her wedding day. The couple literally became “one person” under the law, and that person was always the man. He also automatically became the owner of his wife’s property. But I believe true love thrives best when everyone involved sees eye-to-eye. Suffragists thought so, too. In 1867, suffrage leader Lydia Becker spoke for many contemporaries when she declared:

“Husband and wife should be co-equal. In a happy marriage, there is no question of ‘obedience’.”

So, rather than looking at romance and equality in conflict with each other, suffragists felt equality was a precondition for a happy marriage. It also shows that equality between the sexes isn’t a new concept, which was another reason why it felt relevant to write about the movement. Our rights and attitudes today didn’t just recently drop from the sky; we owe them to countless women and their male allies struggling for justice over centuries. It’s just that for a long time, these people were the underdog. And their work isn’t done.

Perhaps that is why the question keeps popping up in the context of romance novels: aren’t independent women and straight romantic relationships uneasy bedfellows? I always say No, but. I consider myself fairly independent in mind and means, and I still loved falling in love with men. And frankly, I don’t want to choose between being me and being loved. But the devil is in the details. Can we stop the heart from wanting what it wants? No. But can a woman end up sacrificing much of her time and ambitions (such as fighting for the vote!) in a relationship just because she is a woman? Certainly. Jane Austen would have hardly churned out brilliant novels back-to-back with three small kids underfoot plus all the laundry that came with a family in 1805. “In the home is neither freedom nor equality,” American women’s rights activist Charlotte Perkins Gilman lamented in 1910. And by default, man-woman relationships are still gendered spaces. We don’t love in a vacuum; we are influenced by oftentimes subconscious ideas about how a desirable woman should act in relation to another. We’ve all heard about The Mental Load by now, and the stats that say women are still the ones predominantly caring for kids and household in addition to holding down a job. That’s at cross-purposes with having ambitions unless you thrive on three hours of sleep a night. As long as the system is biased against us, a relationship might ask ambitious women to make hard choices.

But when I researched A Rogue of One’s Own, I found that many of the prominent British suffragists & suffragettes had families. Suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst, for example, teamed up with her daughter Christabel to firebomb places. Millicent Fawcett, prominent leader of the suffragists, was both co-worker and carer for her blind husband, Henry Fawcett. And women’s rights activist Harriet Taylor fell so hard for John Stuart Mill, her first husband had to tolerate a very close relationship between the two. The common denominator was that these women all married men who had their backs. Pankhurst’s husband was a suffrage advocate and got his family a butler to take care of their five kids so Emmeline could keep campaigning. Henry Fawcett was one of the strongest proponents of women’s suffrage in parliament before he even met Millicent. And when John Stewart Mill finally got to marry Harriet in 1851, he was so appalled by the fact that he would have ownership over her, he wrote a public declaration:

“…(h)aving no means of legally divesting myself of these odious powers… (I) feel it my duty to put on record a formal protest against the existing law of marriage… and a solemn promise never in any case or under any circumstances to use them.”

Despite these well-known couples, Victorian society liked to deride suffragettes as ugly, frigid, and frustrated, and there are still plenty of cartoons and poems to prove it—the main reason a woman wanted equal rights to men was because she couldn’t get a man. Or so they said. Today, I come across the exact reverse opinion: if a woman wants to call herself strong and a feminist, she has no business losing her head over a man and acting stupid in love. She is, in other words, expected to be immune to a neurotransmitter cocktail that has been proven to be as powerful and addictive as crack cocaine. This strikes me as a tall order. And the result of both these logics is the same: a woman doesn’t get to have it all. At best, she must conform to a certain one-dimensional image, at worst, choose between love and getting her rights. Emmeline Pankhurst would have shaken her head at this—she repeatedly went to prison for her beliefs, and she was also immediately smitten with her husband when she first saw his attractive hands opening a taxi door.

So, in conclusion, I think the suffragists can actually teach us a few good lessons about romance:

1. True romance requires equality

2. Team up with an ally who will hire a butler

3. Fancying a man for his looks and having a political cause are not mutually exclusive

I tried to build my love stories around these lessons. My heroines don’t have to choose between being their complex selves and being loved. In Bringing Down the Duke, Annabelle gets to be beautiful, sensual, and smart, and while equal rights are not yet won when she marries, her husband will help her make it so. Lucie gets to be a brash workaholic, and she also gets worshipped on a kitchen table by the man she wants. And Hattie, the heroine of my forthcoming book—well, her story is still in the works, but since she’s the heroine of a romance novel, I promise she will have a very happy ever after.

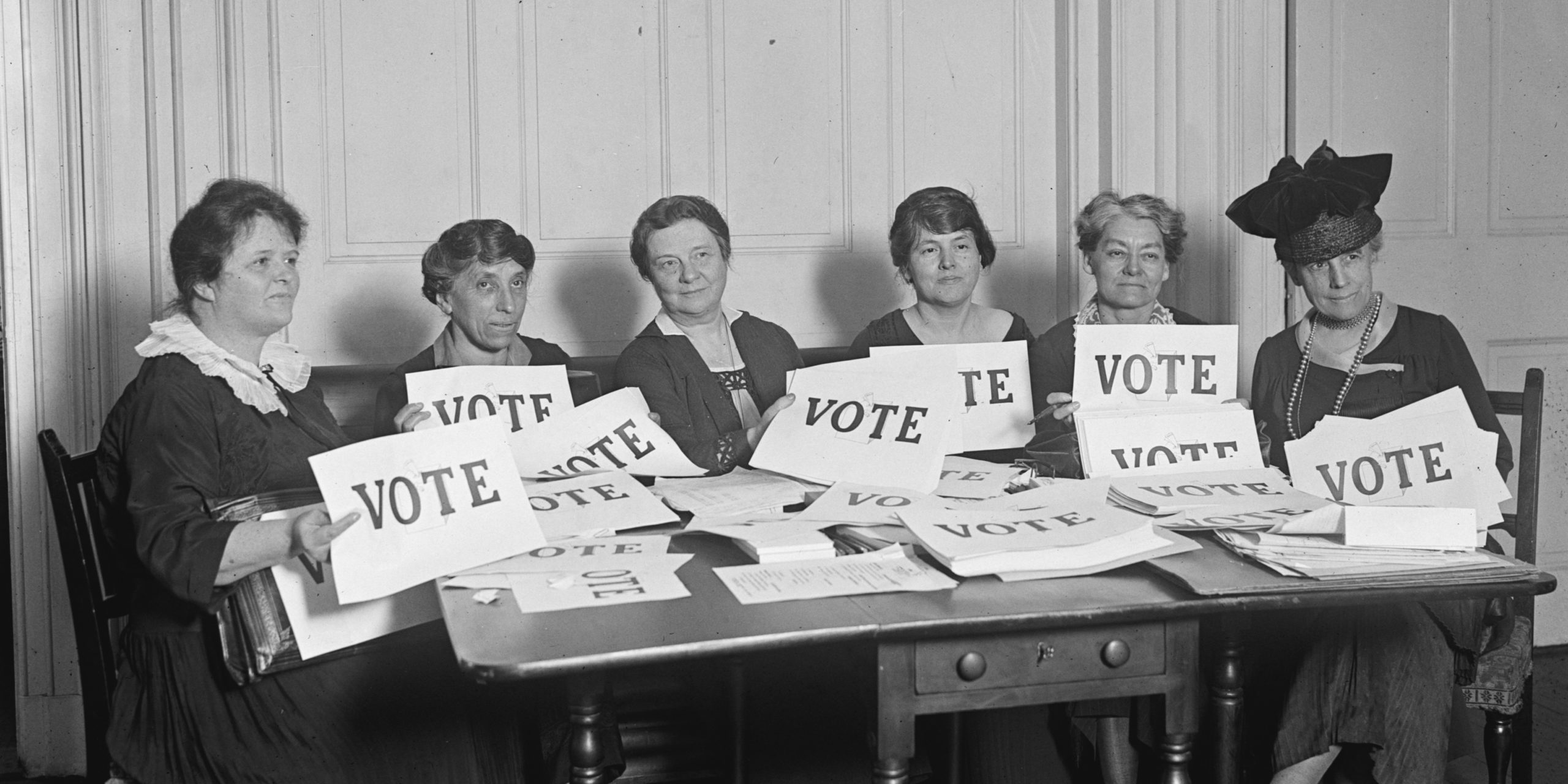

Featured image: View of members of the National League of Women Voters, seated around a table, holding signs that read ‘VOTE’, September 1924. (Photo by PhotoQuest/Getty Images)

[ad_2]

Source link