[ad_1]

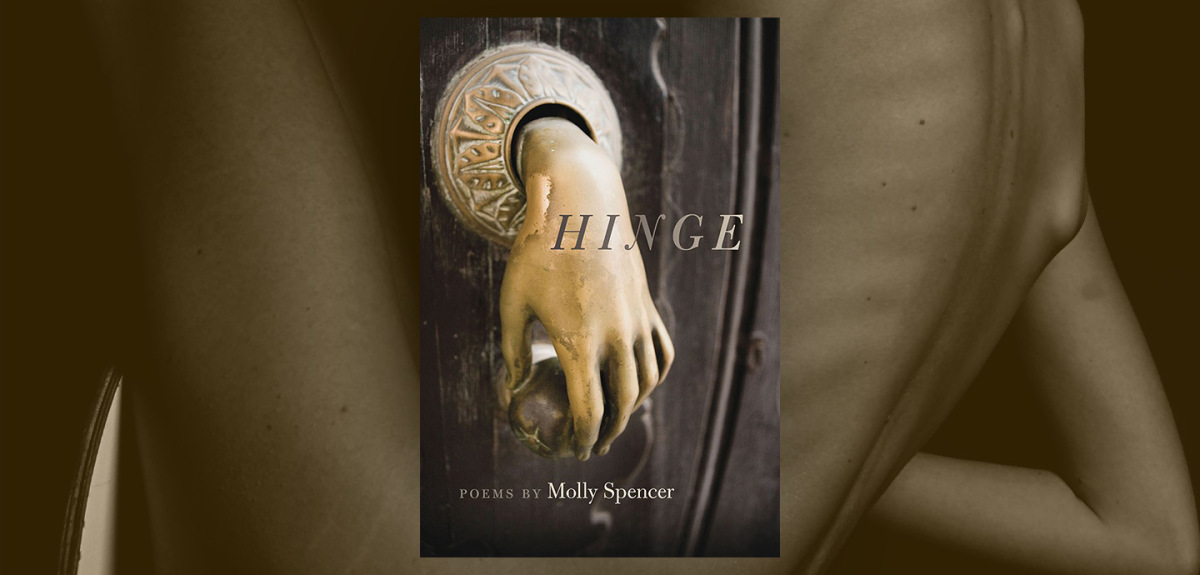

The many hauntings of a mother’s body coalesce in Hinge, a new poetry collection by Molly Spencer. With stories ranging from the ancient myths of Persephone and Demeter to the modern folklore of Peter Pan, Hinge examines a girl’s dreams alongside a mother’s fears.

In Spencer’s poetry, pain is chronic in the body, persistent in the house, and threatening from the stiff harshness of winter in the world beyond. Pain lives in memories of the past as well as in an intense fear of loss in the future. Yet the world of Hinge is not all darkness — it’s also full of light, largely in the form of the speaker’s children. The family represented in these poems is bright and joyful, and Spencer weaves fairy tales into the keeping of house and home. But like any good fairy tale, there is an awareness of something darker creeping in.

In the opening poems, we meet a mother who lives in a state of expectant grief. She looks at her children as figures such as Persephone and Icarus, children whose stories inevitably lead them into danger and death. She sees it in every moment of their lives: her son “runs outside again to play. One feather falls down from his wings,” as if she’s sure he’s already flying too close to the sun.

“Demeter, Searching” is one of the most prominent examples of mythology spun expertly into this specific maternal anxiety — Demeter, who “turn[s] the garden graveward” while looking for her disappeared daughter, finally finds Persephone returned from the Underworld, but Persephone is unable to really explain where she was. “Mom, Mom,” she says. “It’s not the kind of place you can point to.”

The speaker of these poems is motivated by an intense desire to protect her children, to keep them close. She fights with the failing house, the parts of it that float away: “there goes our table, there, the spare key, there go the stories I told them.” There is a desperation as “the children are growing / long and ravenous.” She wonders, “What can I build / that will hold?”

This weakness of the home is significantly tied to a chronic illness in the speaker, to repeated “waking / to a stunted world.” The long poem, “Patient Years,” reveals the depth of this illness, how it overtakes and fills every part of the speaker’s life. It transforms her expectations of her world into something stiff and fearful. Illness lasts for Spencer as a fairy tale curse.

Medical spaces in these poems are akin to the Underworld, and the speaker slips down into an experience that is solitary within the body. Yet, like the mythic Eurydice who is bitten by a snake and slips into the Underworld only for her husband, Orpheus, to come down after her, there is for the speaker “the turning / back to see if the one you love / most will follow you down.”

Winter swirls through these poems, a persistent and powerful setting, and the body evolves and changes as the earth does through the seasons. Spencer’s poetry blends body, earth, and fiction repeatedly, as when she notes that “to become a story / of erosion you must first live / in all the hollow cities / of the bones.”

Yet ultimately, Spencer leads us into spring. Quiet and triumphant, we finally find the speaker has “lived to wake / one day in a room / beyond winter.” A persistent cold that makes joints ache, muscles tighten, and emphasizes every aspect of the speaker’s chronic pain finally dissipates. Spencer notes with humor the ease with which spring seems to come through: “at some point, the cold runs out / of options. The crocus / shoves its dumb face / through wasting scraps of snow.” With relief, there is “the stuck hinge of your body loosening at last.”

The crowning strength of this collection comes from these moments at the end of our narrative, when spring has returned but the memory of winter is still present. For this reason, the speaker’s children, who are far more forgetful, outpace her in their joy, in their readiness to rush out into the world.

“Every morning I startle

at their flight,

their bright, unworried departures.

Door to the jagged world

open wide, and their bodies

clinking through it

like the day’s loose change.”

The fear of loss in the future persists — while perhaps younger creatures aren’t aware of the seasons as a cycle, the speaker remembers. In Persephone’s voice, it is as though the rest of the world above ground has forgotten she ever went away. But Persephone knows she will have to go back down to Hades when the weather turns. “I haven’t yet told you all I know of winter,” the speaker thinks of her children, but she doesn’t say it aloud.

The world of Hinge expresses a need for fairy tales not because they take away pain, but because they represent it. The collection speaks to a very honest fear that lives in so many: that winter is coming and loss hovers on the horizon. But perhaps, as the doctor reminds the speaker, “people learn to live with pain.” Rest and pain are both part of this world. Spencer has crafted a collection that thrives in contradiction, buoying opposing forces that fuse into an eerie, ethereal, ultimately hopeful truth.

POETRY

Hinge

By Molly Spencer

Southern Illinois University Press

Published October 20, 2020

[ad_2]

Source link