[ad_1]

“Acountryisclosingitsborder… (This is not today.)”

“Pandemic/persecution/(The country has no conscience)… (This is not today).”

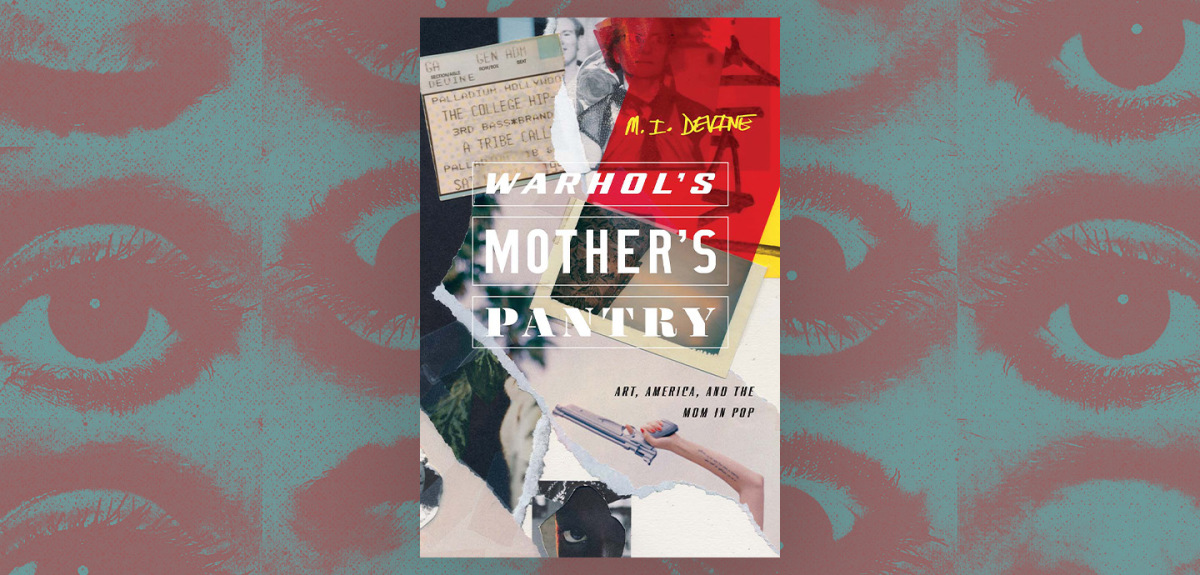

In the first pages of M.I. Devine’s debut collection of experimental essays, Warhol’s Mother’s Pantry: Art, America, and the Mom in Pop, he calls back to the political turmoil of the early 1920s, when a pandemic raged and the U.S. began to close its borders. Amid this chaos, Julia Warhola, mom of pop art progenitor Andy, immigrated to Pittsburgh, PA, where she would raise her family. Julia, herself an artist who would embroider, decorate eggs, and make bouquets of flowers out of tin cans, frames Devine’s inquiry into American pop culture, in which he is less interested in defining pop than in examining and blurring distinctions: between poetry and pop, pop and so-called real life, life and film, film and pop.

Devine’s lyrical mix of memoir and criticism builds on Michael Robbins’ assertion that poetry is “equipment for living,” conceptualizing pop as an infrastructure that holds, shapes, and comforts us “— an index of our exile, what sustains us, what we call home.” Devine focuses on forms — pop’s techniques of reproduction, repetition, and structure, such as refrains, proverbs, selfies, and elegies — to sketch the bones of this pop infrastructure, suggesting that we may not be as alienated from each other as we seem. In an age of streaming services, he wonders, are we all “merely watching atomized and alone, welcoming a new dark age each in our cell” or instead occupying some “shared domestic space where eighty million people watch the same thing”? This, he writes, is the tension at the heart of pop, “that forms and rituals and routines would never do (but what if that’s all we’ve got?).”

Taking repetition and reiteration as one of pop’s central projects, Devine, like Warhol, who obsessively screen printed reproductions of familiar images, revisits familiar texts, noticing how they index change by not changing at all and yet make new meaning with each return. “Pop remembers, recalls, throws back, archives, makes mixes, remixes, and course corrects,” he writes. Devine, Warhol, and pop ask us to think about the power of repetition and wonder, “Why do we prize originality when all we want in the end is to endure?”

With playful, plosive prose rich with cultural allusion, Devine locates the roots of a pop sensibility in the works of literary giants such as W.B. Yeats, T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, Walt Whitman, and John Milton. While Devine reaches beyond the canon to assemble his varied sources, supplementing the authors above with work by Kendrick Lamar, Eimear McBride, Li-Young Lee, Danez Smith, and Hanif Abdurraqib, unfortunately, his engagement with the (white, male) literary giants is much more thorough than with the contemporary artists from which he draws.

Warhol’s Mother’s Pantry may be a challenging read if you don’t share Devine’s love and mastery of poetry or his sweeping knowledge of Western art and the literary canon. Still, Devine is remarkably successful at arraying a pop cosmology that positions his sources so they can talk to each other, upending chronology and genre such that T.S. Eliot samples Hozier, the Kardashians are trying to keep up with Phillip Larkin’s “selfish” sonnets, and John Donne and Kendrick Lamar speak of God in unison. It can’t be easy to put poetic forms like the sonnet, which today’s pop culture aficionados might deem outmoded, in dialogue with your Instagram feed, but Devine does it. “You scroll,” on your phone and “Larkin scrolls,” with his sonnet, which “in Larkin’s hand, becomes an app for measuring” the passing of time, for documenting a life.

Although the book is deceptively dense — abstract, associative, and erudite — Devine is no elitist. His love of pop embraces its inherent mass appeal and delights in its invitation to DIY. In these essays, through Warhol, Devine “reminds us to merely like, celebrate, use, and reuse the things that we like, the things that serve us. Try it. You have some.”

NON-FICTION

Warhol’s Mother’s Pantry

By M.I. Devine

Ohio State University Press

Published November 09, 2020

[ad_2]

Source link