[ad_1]

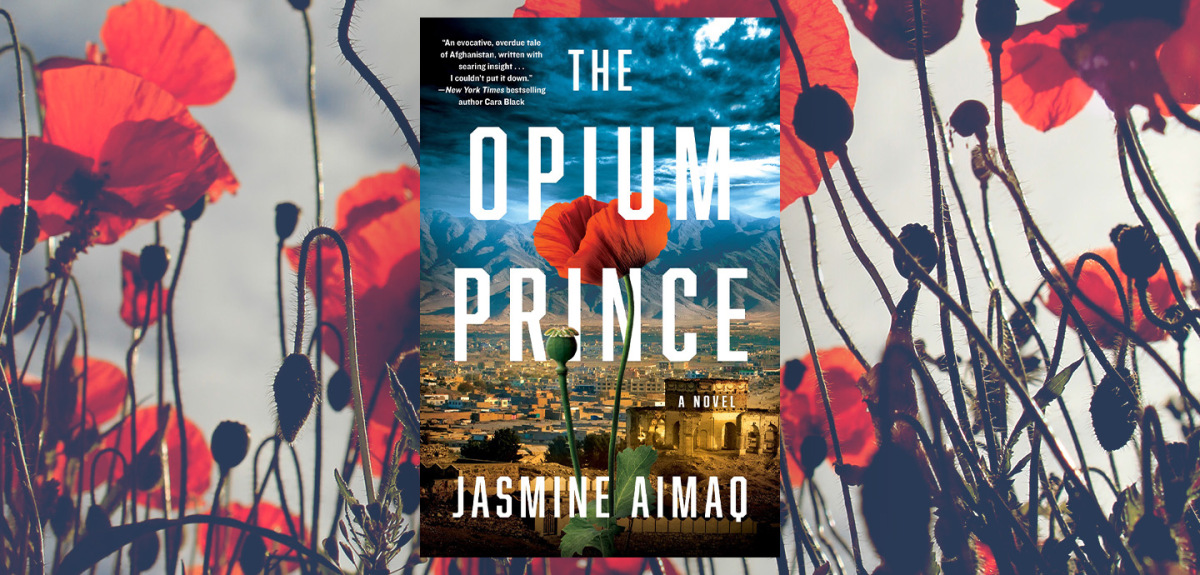

In her debut novel, The Opium Prince, Jasmine Aimaq centers a frequently overlooked aspect of tumult in Afghanistan: if opium were not in demand, possessing it wouldn’t translate into power. A hierarchy – a royalty of sorts – exists around the creation and distribution of opiates in the East, in no small part because of the West’s rampant addictions.

Many think of Afghanistan like this: “The terror. The radicals. The war.” Aimaq begins her list with “The addictions.” She also begins with the past – 1970s Afghanistan, where Daniel Sajadi works for an American foreign-aid agency dedicated to transitioning poppy-fields into other crops and moderating the influence of opium production profiteers.

Daniel’s supervisor recommended hiring him despite concerns that Daniel was “too green” and complaints that “having a last name the locals could pronounce wasn’t a qualification.” (There’s a sense that Aimaq knows Daniel’s position well; she’s half-Afghan and half-Swedish, has lived in both countries, and has substantial experience in the non-profit sector, in both foreign policy and sustainability.)

Daniel’s insecurity appears to revolve around a single, sudden tragedy in the novel’s opening pages; he briefly inhabits an ordinary-day-in-married-life scene, before a violent event provokes political and financial complications. The event has indecipherable connections to the past and simultaneously threatens Daniel’s future, all of which he conceals, struggling to cope independently. His wife grows impatient and demands reckoning: “You think we can just take August seventeenth off the calendar, like it never happened? Just leave it out, like the thirteenth floor of a building?”

By virtue of his last name, one could say Daniel inherited his position. Direct American intervention in Afghanistan might be new, but Daniel’s father also negotiated with opium producers and navigated the industry’s power structures. His father’s still-haunting influence, along with an advisor who worked closely with his father, represent tradition, while Daniel’s efforts (alongside other ambitious individuals) represent an innovative future. As the plot unfolds, Daniel is pulled between these forces.

Aimaq’s vision of Afghanistan includes varied settings: “shops that sold everything from lentils and onions to Timex watches and American jeans,” “patches of crushed, dirty snow” in fields, and “the garden capital” of Paghman in the western part of Kabul Province with its “manicured hedges” near the replica of the Arc de Triomphe. In the city of Kabul, characters visit the “oasis of green that harbored a mosque” at the Gardens of Babur, as well as the Shor Bazaar, “where musicians sat in crooked stairwells, the sounds of the tabla and rubab rising in the air.”

The novel brings domestic scenes to life, too, like the house filled with the “aroma of saffron, cardamom, and rosewater mixed with hair spray and the women’s clashing perfumes.” The contrast in scents here is one of several minor conflicts which bolster the narrative’s broader volatility. Like how the ocean is described as “neither blue nor green” and an aid worker picks his way through a wet field after forgetting his fieldwork shoes.

Relationships between individual characters are characterized by unease and, occasionally, broader struggles for power. Many people seek to increase their privilege and influence, including the Soviets, the Communists, the opium khans, the religious leaders and adherents, and, more recently, Americans on the ground. There are as many different forms of power, from “the power that came from not caring too much what happened afterward” to the power to “play without rules,” to the power to “speak for the information” because “information never speaks for itself.”

Singling out specific relationships and communities risks spoiling plot developments. Though rooted in the historical events that led to the Soviet-backed Saur Revolution in Afghanistan, The Opium Prince reads like a thriller. Readers are thoroughly engaged in Daniel’s disorientation; he’s unsure whether specific personnel truly represent the interests with which they outwardly align, unsure of individuals’ true power and privilege. His uncertainty mirrors readers’ confusion: “So it’s either Russian puppets or a future of backward superstition? Are you sure you know what you’re doing?”

The response is not a resolution: “We can’t predict the future—we can only turn our backs to the past.” Because the “world is full of people chasing after other people’s crumbs.” But how can we navigate this labyrinth in only a few hundred pages? Especially when salient information is uncovered only when characters confront conflicting versions of the truth? There is a mindful ambiguity to the telling of The Opium Prince, wherein “Snippets of the past rearranged themselves, changing colors.”

Aimaq’s professional and life experiences recommend her to the task of presenting a nuanced understanding of competing and undermining influences at work in Afghanistan. More fiction-writing experience would have allowed her to explore more than one alternate perspective, to secure readers with time-and-place headers to counterbalance the narrator’s insecurity, and to stylistically link the prologue and epilogue so both feel equally organic to the narrative. Nonetheless, this debut novel is compelling and Aimaq’s observations astute. The Opium Prince is ambitious, complex and multifaceted – what every novel about a nation should aspire to be.

FICTION

The Opium Prince

By Jasmine Aimaq

Soho Crime

Published December 1, 2020

[ad_2]

Source link