[ad_1]

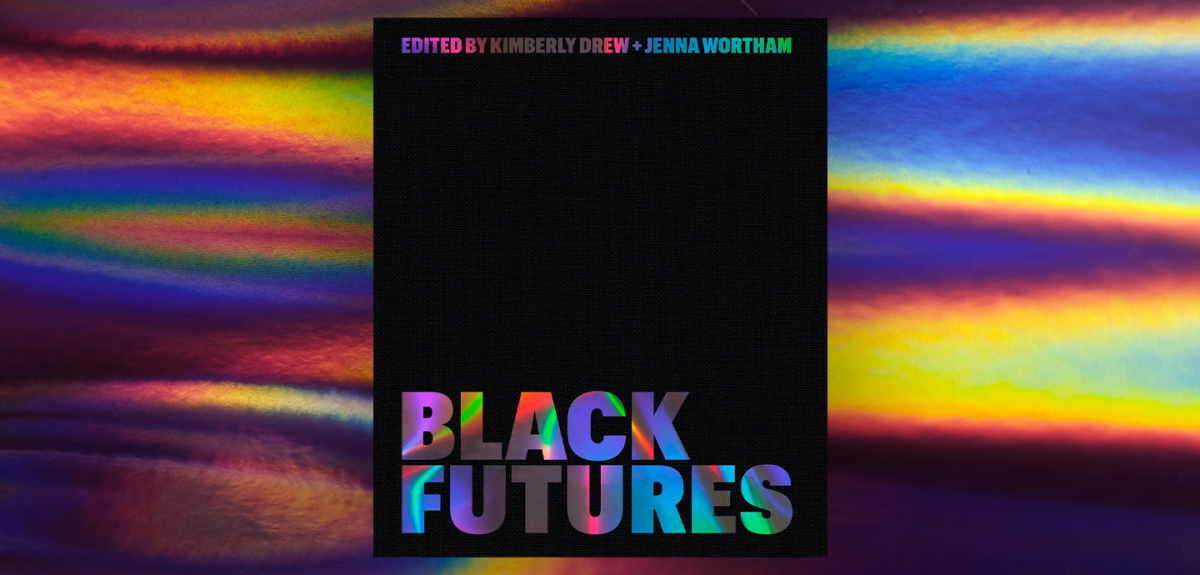

In the forward to Black Futures—this eclectic anthology of Black imagination and achievement—co-editors Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham share its central question: “What does it mean to be Black and alive right now?” Of course, that “right now” is necessarily a misnomer, because the world has changed, is changing, from the time this project was conceived in a chat between the editors—colorfully reproduced in the introduction—to its publication. From the moment one cracks open this 527-page book—and this is a compilation to be savored in hard copy—it’s evident that Black Futures is no coffee table doorstop, relegated to a corner of your living room for the guests you’ll have again in the future. As thorough as it is—divided into sections such as Power, Joy, Justice and Memory—the editors inform readers at the outset that it’s the “first iteration.” It’s clear that the Herculean task before Drew and Wortham was as much about finalizing what to include as it was about the Abrahamic sacrifice of what to omit, for now.

The ambitious content is a blend of subject matter, through visual images and literary conversations from a full expanse of sources, including social media, photography, art installations, articles, texts, essays, studies and collaborations. The only missing element—understandably—is live performance (though there are discussions of theatrical events such as Jackie Sibblies Drury’s Fairview), which underscores how this compilation is a jumping off point for discussion, rather than a static destination.

There are thematic sections that encompass both the political and personal: from “Justice” to “Power;” “Joy” to “Black is (Still Beautiful);” from “Memory” to “Legacy;” yet the subject matter wanders organically via such broad headings. There are many connections across these rooms, both through specific links suggested by the editors, as well as the individual delights of paging back and forth, performing a kind of Luddite hyperlinking. Reading Hanif Abdurraqib’s “On Times I Have Forced Myself to Dance,” there are suggestions in barely perceptible print on the lower left hand side of the page to several articles, such as Jasmine Johnson’s “#OptimisticChallenge: Decisive Black Joy” on page 152, which then directs you to Kia Labeija’s “On and Off Again” on page 336 as one of a number of options for further engagement.

Even without Drew and Wortham indicating in the introduction that this isn’t a linear narrative, one’s natural inclination is to have an active experience: open anywhere as a divinatory tool and see where it leads. There’s a suspension of time, topic and geography, like the best of parties, in which you come across those familiar to you, and through them, new, thought-provoking voices.

The editors have taken on a singular challenge by marrying the concrete experience of a book with the expansiveness of such subject diversity, along with a flexible temporality that uses the date of publication as a touchpoint that ripples backward and forward. The result is both open and finite, acknowledging the limitations of an arbitrary moment in time, yet the sum of its parts is nothing short of exhilarating. It’s an unexpected irony that this traditionally printed product inspires one to search the internet for more, and equally that these words and images somehow appear more durable on a fungible page than in the permanent cloud.

The book does not purport to speak for everyone, or every era, just as there is no monolithic Black voice or experience. The topics and contributors are global in subject and scope: ethnography and scholarly theory bump up against calls for action about Flint, Michigan, nearby are horrific statistics about the murders of Black trans people; well-known artwork and songs are interspersed with interviews and dialogues, and there are even recipes. Poets like Eve Ewing and Danez Smith inhabit the same air as Lawrence Burney’s essay on Baltimore’s Arabbers, which shares the stage with causes such as Appolition. The ending of Mecca Jamilah Sullivan’s essay about Ntozake Shange could be extrapolated to the subjects of the entire volume and the editors’ intentions overall: “In Black Feminist theory, we believe in the present tense. Our lions have not walked; they walk. Our she-roes have not lived. They live.”

As “Blackness is infinite”, this is a book in gerund form: even in immutable hard copy, it is a state of being, rather than a conclusion. Yet it’s critical to mark these stories, even though—maybe especially because—the ultimate compendium can never be complete. If one never starts because of the enormity of the task, then nothing will be remembered. If one waits for the full story, no story will be told.

Perhaps some readers might wish that different subjects were included. Other editors might offer an alternate restructuring, even if they used the same components. Indeed, one suspects that Drew and Wortham would likely alter their emphasis if they began the collaboration now.

Black Futures is political—as life is political—and joyous. One of the great accomplishments of this book is that though it addresses the systemic harm, literal and figurative, done to Black people, which incites sorrow and rage and underscores the immediate demand for justice and parity, the overall experience is that of a dwelling full of pride, elation and opportunity. The editors have artfully fashioned a mansion without limitations, and hint at rooms still to be seen, perhaps to be filled by subsequent voices and editions.

Normally, one expects reviewers to have thoroughly read and analyzed the book in question before setting pen to paper. But I’m not done with Black Futures, even though I’ve gone through every page in the book (I do think it may single-handedly revitalize the bookmark industry). Early into my first foray into this boundary-less continent, I wished I could launch a robust discussion group before I reviewed it. A book that so meaningfully creates diverse discourse necessitates a community conversation.

In her “Primer For Blacks,” Gwendolyn Brooks wrote:

“Blackness

is a title,

is a preoccupation,

is a commitment Blacks

are to comprehend—

and in which you are

to perceive your Glory.

[…]

The word Black

has geographic power,

pulls everybody in:

Blacks here—

Blacks there—

Blacks wherever they may be.”

To quote Alisha Wormsley’s memorable art installation:

“THERE ARE BLACK PEOPLE IN THE FUTURE”

And there is no future without Black people. Black Futures is an admirable, generative and thoroughly essential curation that offers space and spaces from which to crusade, celebrate, reflect, and create more archives and platforms for Black futures.

Anthology

Black Futures

Edited By Kimberly Drew & Jenna Wortham

One World

Published December 1, 2020

[ad_2]

Source link