[ad_1]

One of the enduring pleasures of poetry is how like wine, or friendship, it improves as it—and you—age. Re-read the 2019s or the 2000s, or the 1966’s to savor the context of our past, through your present vantage point. Other than live theatre, there is no other medium such as poetry so well-situated for re-reading; to gather new meaning, and to reframe one’s own perspectives and individual growth. Having barely made a dent in reading every poetry collection released in this unimaginable year, this isn’t intended to be a “best of” list. Here is a palmful of the books that feel especially attuned to this year and experiences of loss. But don’t stop here: read their sisters and brothers, in English or as a translation.

When contemplating personal challenges, we often say, “well, it’s not life and death.” Yet as a nation, as a people—a fractious, divided people—2020 has been a year full of critical issues that are all about life and death. Of individuals, of institutions, of the environment, of our very humanity. Each of these collections deals with such issues, using language—at times deconstructed—to express personal truths with societal import.

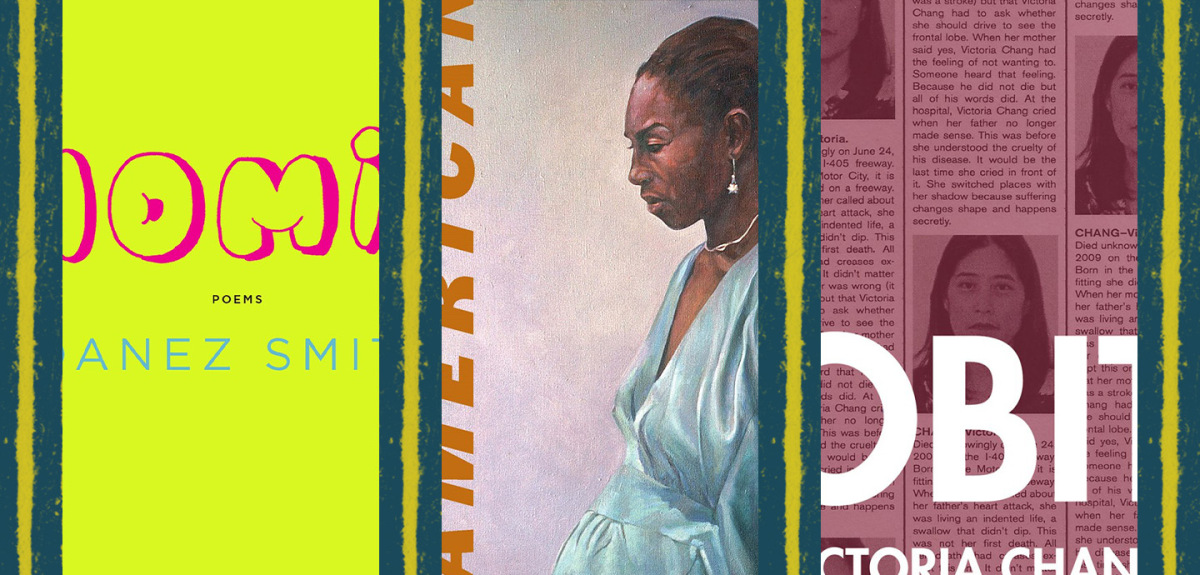

In Obit, Victoria Chang expresses her grief after the death of her mother in brief and powerful obituaries to all that she has lost. Her exploration of the accumulative bereavements are especially memorable for how she renders the inexpressible—the unutterable sounds of mourning—into language that marks the reader. In “My Father’s Frontal Lobe,” she ties together his loss of language after a stroke with her own miscarriage, creating a space that encompasses all that cannot be regenerated through language, through the possibility of words to communicate pain and make connection.

“My Father’s Frontal Lobe—died

unpeacefully of a stroke on June 24,

2009 at Scripps Memorial Hospital in

San Diego, California. Born January 20,

1940, the frontal lobe enjoyed a good

life. The frontal lobe loved being the

boss. It tried to talk again but someone

put a bag over it. When the frontal

lobe died, it sucked in its lips like a

window pulled shut.

[…]

… At the funeral for his

words, we argued about my

miscarriage. It’s not really a baby, he

said. I ran out of words, stomped out

to shake the dead baby awake. I

thought of the tech who put the wand

down, quietly left the room when she

couldn’t find the heartbeat. I

understood then that darkness is falling

without an end. That darkness is not

the absorption of color but the

absorption of language.”

For the many who straddle cultures, there are a number of specific questions to address via their poetry. Where is home? What is it to be foreign to oneself, wherever you are? And especially: how does language both ground and propel, particularly those whose cultural lives are bifurcated? In “Wings of Return,” from DMZ Colony, the winner of the National Book Award for Poetry, Don Mee Choi examines identity and origin through language and geography.

“In December 2016, I returned to South Korea. I returned in the guise of a translator, which is to say, I returned as a foreigner. And as a foreigner, I was invisible to most. I flittered about in downtown Seoul searching for my child self that had been left behind long ago. As a foreigner, I understood only the language of wings—the wings on totem animals on old palaces where I used to run around and play. The traditional tiled roofs I grew up beneath had grown wings, as had the mountain peaks behind Gwanghwamun Square. They no longer recognized me in a crowd of other foreigners—tourists, rather. Nevertheless, I went on searching for more wings, my language of return.”

Un-American, Hafizah Geter’s debut collection, also dissects the immigrant experience and the freighted question of who is American and who is not. Yet it is equally powerful as a tender and painful exploration of familial conflicts and connections. Her memories and perceptions are often so different from her sister’s and parents’ that they could each be from different countries, even when they inhabit the same space. Throughout this collection, one considers what unifies us, and what tears us apart, as well as how the desire to forge a new identity often shears away parts of us we may not want to lose: “Tonight the distance between me, my mother, and Nigeria / is like a jaw splashed against a wall.”—

Memory looms large in Geter’s collection—“I am a test of how far a daughter’s memory can go”—as comfort, as pain, as shackle, as flight.

In Homie, Danez Smith creates an intimate landscape, writing to, for and about “the homies who keep me.” There’s a musicality to the poems that marries content with cadence so well, with poetry that shares love, and also can be weaponized, as they write in “my nig:” “this ain’t about language / but who language holds.”

In the powerful “my poems,” they give fair warning in a litany of sharp statements that turn poems into nouns, verbs, objects and actions that won’t be stopped:

“my poems are fed up & getting violent.

[…]

i mail a poem to 3/4th of the senate, they choke of the scent.

[…]

i poem ten police a day

[…]

i poem them all. i poem then all with a grin, bitch.”

Justin Phillip Reed raises the stakes of poetry and language in Malevolent Volume, where he takes on myth, history, expectation and tradition, to create a new language and a new multitude, in a singular voice and style. His linguistic contortions and lusciously complex intertextuality demand that readers engage as full partners in the creation of meaning.

“I metronomed now toward

“My life in poems” and then “I want to live,”

tore “my accountability to a community” from “I can’t bear

to be among,” turned from “violence is a resort” to

“the careful pursuit of beauty” and back.”

Like the others, Reed explores loss, external and personal.

“In the age of loss there is

the dream of loss

in which, of course, I

am alive at the center—“

These poets—these verses—are a minute fraction of this year in poetry, which also includes chapbooks, those gems of talent that often don’t make it to year-end lists. If there is a final recommendation to be made, it’s to explore the independent presses that are championing the multitude of verses in our midst, here and abroad. In this age of loss, this dream of loss, poetry connects us to the global consciousness, to each other, and to ourselves.

[ad_2]

Source link