[ad_1]

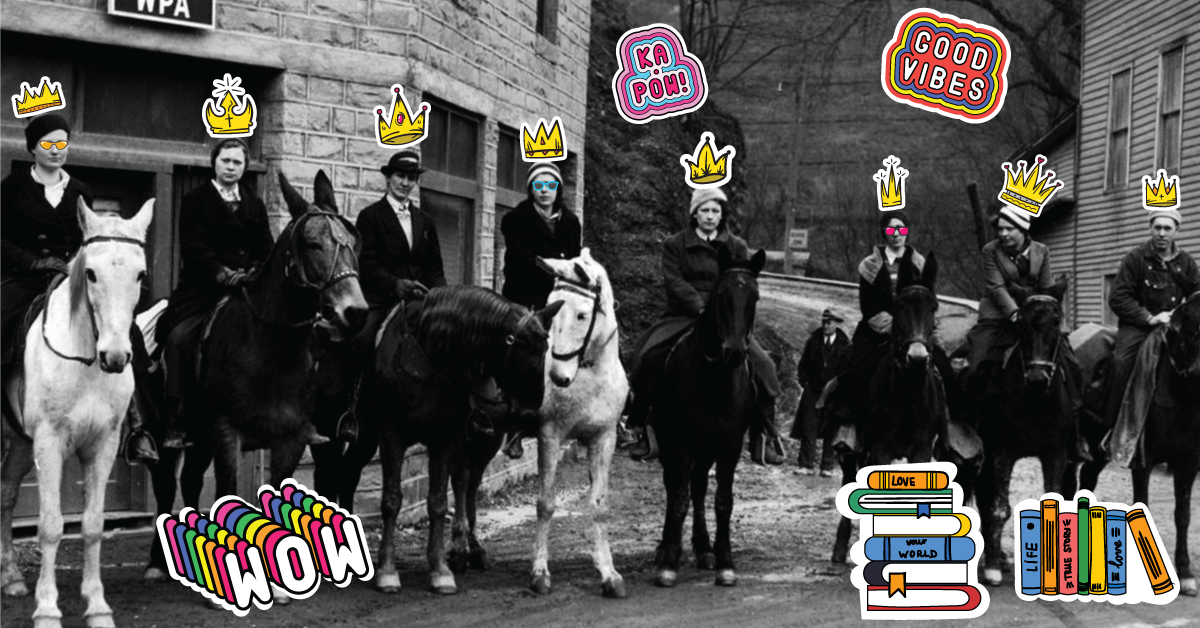

Between 1935 and 1943, a Works Progress Administration program called the Packhorse Library Program brought books directly to the homes of people in rural Appalachian Kentucky. At the time, roughly 31% of the people living in this area were illiterate. Believing education was the key to bringing people out of poverty, President Roosevelt hired “book women” to make book deliveries to families. Here are some interesting facts about this program.

- The first Pack Horse Library was actually created in 1913 by a woman name May F. Stafford and was funded by coal baron, John Mayo, in Paintsville, Kentucky. Mayo’s death in 1914 brought an end to that program, but Elizabeth Fullerton, a woman active with the WPA, borrowed the idea in 1934. With the help of a Presbyterian minister who offered his library to the WPA if they would pay people to deliver the books to those who couldn’t access a library, the program not only rallied but expanded to eight different locations by 1936.

- Women, both single and married young mothers, were hired to make the book deliveries. They rode on horses or mules—either their own animal or a “rented” one from a local stable owner. There were few established roadways, so the going was difficult and sometimes dangerous. The distance between homes potentially kept the women on their routes from sunup to sundown.

- Each packhorse librarian might travel as far as 500 miles and deliver as many as 3,500 books in a single month! Regardless of the number of hours required or how rough the passage to make the deliveries, the riders received a standard salary of approximately $28.00 a month. Despite the difficulty, given how few opportunities to earn a wage were available at that time to women, they were happy to earn it.

- Although the WPA paid salaries, it didn’t provide funds to purchase materials. All of the books used in the program were donated. Individuals, church groups, and service organizations collected books of all varieties, magazines, and even postcards. These items stocked the libraries’ shelves.

- One head librarian organized the materials at each library’s location and prepared the packs for delivery. Most commonly, books were carried in saddlebags, but some librarians used homemade hickory baskets to transport the books. Four to ten riders from each location, depending on the number of people served, took the items directly to families.

- No materials were wasted! Some of the most popular items for adults were themed scrapbooks made from postcards or pictures cut from tattered magazines. Recipe books were particularly sought after and became ragged from use.

- Not everyone welcomed the packhorse librarians, though. Suspicious of outsiders, unsure of the books’ contents, or resistant to change, some families refused to let the librarians draw near. To win these families’ trust, the librarians stopped at the edge of yards and read Bible passages aloud. Interestingly enough, the most requested book for the duration of the program was the Bible.

- Children were most receptive and often ran to meet the riders, eager for picture books. The grown-ups in the house enjoyed such titles as Robinson Crusoe and were particularly fond of Mark Twain’s works. Many adults weren’t able to read, so illustrated books were also prized, and children’s reading abilities blossomed as they read aloud to their parents.

- Local families contributed to the program by sharing their favorite recipes, home cures, or quilting patterns. These written pieces of information were accumulated, pasted into scrapbooks, and shared with neighboring communities.

- School children in larger cities participated in the packhorse program by doing fundraisers, such as penny drives or bake sales. With the funds, they purchased books and then donated them. Despite the economic difficulties of the time, people’s generosity kept the programs in operation.

The United States going into war and an end to the Depression brought, by default, the end of the packhorse librarians’ deliveries. At its heyday, there were close to 30 pack horse library programs that put literature into the hands of nearly 100,000 families. One can only imagine how many lives were positively impacted by the opportunity to learn to read, to be exposed to great literature, and to expand their knowledge. Both my recent book, The Librarian of Boone’s Hollow, and Jojo Moyes’ recent novel, The Giver of Stars, center on packhorse librarians.

Featured Image: Nyesha Viechweg

[ad_2]

Source link