[ad_1]

In an interview for The Believer, graphic artist turned novelist Peter Mendelsund elaborated his own approach to literature by using a surprising comparison to another art: puppetry. The audience of a puppet show is observing two stories simultaneously, “the diegetic material that the puppets are performing, and the actions the puppeteer is performing.” In other words, they’re watching both the puppets on stage and the puppeteer pulling the strings.

In Mendelsund’s hands, this simple observation about puppetry makes for an experimental approach to novel writing. In his new novel, The Delivery, the results are often frustrating, but will be thought-provoking for readers who are interested in how such an approach can shape the novel form.

The plot—what the “puppets” are doing on stage—is seemingly simple: The Delivery tells the story of a character as he transports packages from a warehouse into the hands of well-to-do city residents. The Delivery Boy is hassled by building doormen, ignored by customers, and abused by his Supervisor. The work is alienating and exploitative, even more so than the real-life gig work like Grubhub or Uber that it resembles—it is revealed that the Delivery Boy is essentially an indentured servant, given lodging and a bike by the shadowy company that “employs” him.

But the solitary, repetitive work, which involves traversing the city and near constant waiting, affords the Delivery Boy plenty of time to take refuge in his own mind. Mostly he thinks about two things: his efforts to learn the language of the city in which he finds himself, and his affection for N., a dispatch girl who is cold towards him but seemingly protective of his fate.

It is against this backdrop of the protagonist’s thoughts, observations, and desires that the reader can make out the puppet strings and the silhouette of the puppeteer. Mendelsund’s first technique for disrupting the plot is breaking up the narration with a barrage of parentheticals, line breaks, and horizontal rules. Sentence fragments give snapshots of what the protagonist sees in his day, and each short chapter might contain a single scene, or a cluster of observations. The first chapter simply reads “Delivery 1: ★★”

The unconventional use of syntax slows the pace of the book, and imitates the rote, hurry-up-and-wait work of the protagonist. Later in the book, as the protagonist gains fluency in the language of the city, the book’s style swings from fragments to long sentences that run on for pages. Here Mendelsund eliminates the incessant line breaks but keeps in the parentheticals, which weave in the perspective of an omnipresent, first-person narrator, distinct from the Delivery Boy yet familiar with his story.

The puppet analogy is most literally realized in the interplay between the Delivery Boy’s narrative and the voice of the narrator. The narrator, who has been for the duration of the novel silently pulling the strings of the narrative, is now so participatory as to interrupt the Delivery Boy’s quest with his own parenthetical story:

“The delivery boy peered into the darkening orchard and saw

(A picnic.)

(No.)

(Sorry.)

(That doesn’t go here.)

(But still.)

(It was the fall, and I was with my parents. Beer foam on my mother’s upper lip …”

The technique is frustrating, in no small part because the story of the narrator is in many ways more descriptive than the story of the book’s ostensible protagonist. The book never fills in key details about the Delivery Boy (his name, most notably), instead opting for a conscious erasure of the character. Just as the Delivery Boy is invisible to the customers he serves, he is invisible to us, the readers. In the end, Mendelsund is more interested in exploring the complexities of narrative and less so about fleshing out the life of his protagonist.

A reader’s enjoyment of The Delivery will mostly depend on if they share Mendelsund’s interest in these meta-fictional techniques. For my part, I found the most damning failure of the book was that its method of erasure-as-portrayal extended to its discussion of migration within the Delivery Boy’s life. It is not just that the Delivery Boy is unnamed; so too is his home country, his native language, and the nature of the conflict that forced him from his home.

By excluding any specific cultural details, the Delivery Boy’s story is unmoored from history. Rendering the book ahistorical necessarily leaves it apolitical as well. There isn’t any specific story the book wants to tell about the political violence in the protagonist’s past, nor is there any apparent relationship between his home country and the metropole. It’s disappointing that this book has nothing of substance to say about, for instance, the over ten million undocumented immigrants working in the US today in similar conditions to the book’s protagonist.

The Delivery is a unique novel that devises clever ways to tell its story, but fails to ground itself in basic techniques of character development and plot. This experimental novel creates a compelling new world, but it’s hard to parse what exactly it wants to say about ours.

FICTION

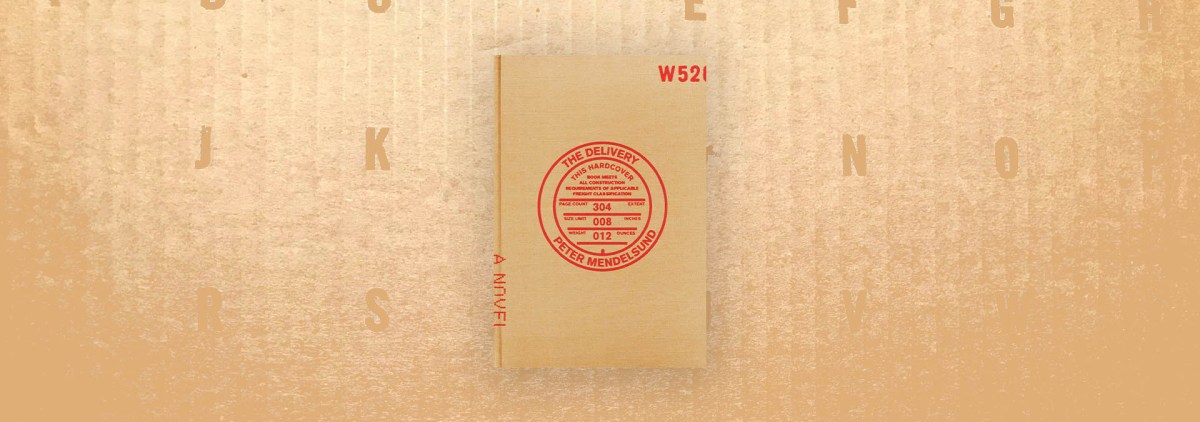

The Delivery

By Peter Mendelsund

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Published February 9, 2021

[ad_2]

Source link