[ad_1]

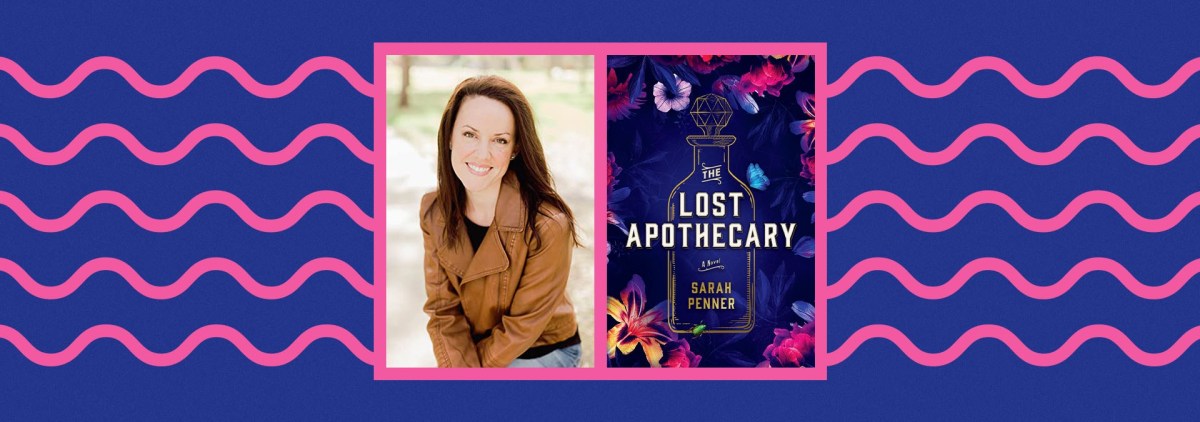

Releasing a debut novel is always a fraught endeavor, and in a pandemic, it’s even more so. But the luckiest debut novelists see buzz building for their books well in advance of publication. Right now, that buzz belongs to Sarah Penner and her inventive, compelling historical novel, The Lost Apothecary. It’s been named among the most anticipated books of 2021 by Newsweek, Good Housekeeping, Hello! magazine, Oprah.com, Bustle, and many, many more. The talented Penner bursts onto the historical fiction scene with a dual-timeframe novel that follows three fascinating women: an apothecary who only allows her poisons to be used to kill misbehaving men, a clever girl whose curiosity about the apothecary leads her to quickly get in over her head, and the modern-day woman whose discovery of an 18th-century apothecary vial spurs her to investigate the unknown as a distraction from her crumbling marriage. I talked to Sarah about forging a connection with the past, what makes Georgian London special, and writing feminist historical fiction.

Greer Macallister

I’d never heard of “mudlarking” before your book, but I love that it serves as the inspiration for the novel and the connection between your two timeframes. You even have a piece of clay pipe from your own mudlarking experience, right? Share a little bit about how that experience, and your other research, helped you form a stronger connection with the late 18th-century period you write about in The Lost Apothecary.

Sarah Penner

In the summer of 2019, I found myself along the banks of the River Thames in London, wearing old tennis shoes and blue latex gloves. I was mudlarking, which means playfully hunting the riverbed for old or valuable artifacts. In my backpack was a small card — my temporary license from the Port of London Authority, granting me access to go mudlarking on the river’s foreshore. Over the course of several days, I went down to the river three separate times, finding an assortment of pottery, clay pipes, metal pins, and even animal bones.

Mudlarking has been around for hundreds of years. Victorian children used to scrounge around in the mud looking for items to sell. Today, mudlarking isn’t meant to support the livelihood of a family, but instead represents a pastime for locals and tourists alike. I first learned about mudlarking years ago, while reading London in Fragments: A Mudlark’s Treasures by Ted Sandling. In the book, he shares striking images of interesting things he’s found near the River Thames. It is here that I first spotted a fragment of a mid-seventeenth century delftware apothecary jar, and the inspiration for The Lost Apothecary was born.

Researching the many herbal and homespun remedies for this story was a time-consuming, albeit entertaining, task. I spent time in the British Library scouring old manuscripts and druggist diaries; I reviewed digitized pharmacopeias; and I studied extensively some well-known poisoning cases in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. I was surprised by the number of plants and herbs that are highly toxic, and I was fascinated while reading about the clever, if ineffective, remedies used by the predecessors of modern-day pharmacists.

Greer Macallister

It’s not unusual for historical novels to follow two characters in two timelines to tell a dual-stranded story, but I love that you’ve taken that model a step further and entwined young Eliza as a narrator alongside Nella in the 1791 timeline. At what point did you make that decision — early in planning, or did it come later in the drafting process?

Sarah Penner

The decision to include Eliza is one I remember well. I was sitting at my desk, having just written the scene in which Nella, the apothecary, dispenses poison to a young girl named Eliza. I asked myself, “what would the reader most want to know now?” Well, of course, the answer was clear: they would want to see what this young girl planned to do with the poison. They would want to follow her home, step into her life, and stand alongside her as she made a very brave and scary decision. This had to be told from Eliza’s point of view; there was really no other option. I didn’t want to make it a flashback or a conversation later in the story; instead, I wanted the reader in the room with Eliza at the very moment she withdrew the poison from her pocket.

As I began to flesh out her point of view, Eliza easily became my favorite character — and many early readers have said the same. She’s a source of comic relief at times (she’s a curious girl with a tendency to insert herself into conversations) but she’s also a foil for the apothecary Nella, showing the purity of spirit that is present in someone who hasn’t yet been run haggard by life’s unfairness. When she first comes into the apothecary shop, she draws a line in the soot with her finger, revealing the unblemished stone beneath. It’s a metaphor: as the story progresses, she unconsciously begins to peel away at Nella’s layers, showing that the sinister apothecary does still have goodness in her.

Greer Macallister

Historical fiction that centers the stories of women clearly resonates with many readers these days, but some readers call these stories of bold, active women anachronistic, claiming that modern authors are just imposing our worldview on women of the past. How do you reckon with that potential criticism? Would you describe this as a feminist novel?

Sarah Penner

The apothecary in my story has a very important rule: the name of every woman who steps into her shop must be recorded in the apothecary’s register. She says, “For many of these women, this may be the only place their names are recorded. The only place they will be remembered. There are few places for a woman to leave an indelible mark…But this register preserves them — their names, their memories, their worth.”

When critics say that modern authors are imposing our worldview on women of the past, I heartily disagree: women have always been brave, but like the apothecary says above, they were often left without a voice — no place to leave that indelible mark, particularly if they were middle- or low-class. As authors, we might have to make a few assumptions about motive, but there’s zero doubt that the women of eras past were frustrated, voiceless, and thus often rebellious.

There are many feminist elements in The Lost Apothecary. It’s a story about three women, each yearning for things that have been hindered, in some way, by the men in their lives. And as the apothecary interacts with each of her clients, we learn that her customers — all women — have encountered the same. It makes for thought-provoking discussion, the many ways the women in the story react to this hindrance. Some approaches are sinister, others are not. It opens up questions of morality and our rights as women, and it’s interesting to consider how those rights have changed (or not) over the last two hundred years.

Greer Macallister

Certain time periods tend to be more popular in historical fiction these days — such as, of course, World War II. The late 18th-century period you’re writing about doesn’t crop up as much. What did you find particularly intriguing about it? Do you feel there are other stories from that time waiting to be told, by you or other writers?

Sarah Penner

I’ve been studying 18th-century (Georgian) London for many years; my bookshelf is teeming with volumes on the subject. It was such a scandalous era, yet authors don’t seem to write much about it — which I think is a missed opportunity! It was a time of brothels, corrupt police, the Gin Craze, terrible diseases, and a king suffering from recurrent bouts of mania.

Lucky for me, it was also the perfect era to set a story about a poisoner apothecary, and here’s why. Until the mid-19th century, death examiners were unable to detect the presence of poison when performing autopsies; forensic toxicology did not yet exist, and thus poisoning homicides are rarely mentioned in 18th century bills of mortality. So, setting my story in late 18th-century London meant the apothecary could “get away” with her sinister behavior; even fifty years later, the poisons she dispensed would have been identified during an autopsy.

I’m pleased my publisher had no qualms with a story set in the 18th century, despite it being an unusual choice for historical fiction. I do hope that more authors consider writing stories set in this era; there’s so much untapped opportunity to explore.

Greer Macallister

Obviously, launching your debut novel into a pandemic is, let’s say, suboptimal. The traditional book tour is certainly off the table. But social media and virtual events provide opportunities to connect with readers without meeting in person — have you had good experiences with those so far?

Sarah Penner

When the pandemic began and it was clear the “traditional” debut experience would not be happening, I was admittedly disappointed. But in hindsight, I can honestly say I wouldn’t change a thing. The breadth of readership I’ve been able to reach via virtual events has far exceeded anything I could have done in-person. For instance, I participated in a virtual event with Kristin Hannah, Lisa Scottoline, Greer Macallister, and Michaela Carter, and this event drew thousands of attendees. That type of visibility is rare for a debut and would not likely have happened at an in-person event. I’m also very fortunate that several of my launch events will be hybrid, meaning in-person but streamed live. The event on March 2, the day of my launch, is being hosted by a local bookstore with a large event space, so we’re able to safely bring in a group of people while adhering to all safety requirements. It isn’t a national tour, of course, but it will mean so much to have a few loved ones there in the room with me on the night of my launch.

HISTORICAL FICTION

The Lost Apothecary

by Sarah Penner

Park Row Books

Published March 2, 2021

[ad_2]

Source link