[ad_1]

In the author’s note to Festival Days, the new collection from Jo Ann Beard, there is a funny kind of dedication: Beard thanks the magazine Tin House for being willing to publish four of the pieces included in this collection “without undue fretting over genre.” I imagine Beard has been negotiating genre with publishers for her entire career. Her breakout essay “The Fourth State of Matter,” about a traumatic week of Beard’s life, was labeled a “Personal History,” despite appearing in the June 1996 fiction issue of The New Yorker.

Earlier in the same note, Beard describes that same anxiety around genre in more playful terms. She says that the fiction pieces in Festival Days “are also essays, in their own secret ways, and the essays are also stories.” The collection at large proves her point. Ostensibly, the forms gathered in the collection are varied: two pieces of fiction, two nonfiction vignettes, two craft essays, two reported pieces, and the long, autobiographical essay “Festival Days” that gives the collection its title. But despite these differences in form, each piece feels like it belongs to a category of writing that is uniquely Beard’s own.

I began to recognize the hallmarks of Beard’s style after reading this collection; reading “The Fourth State of Matter” now feels uncanny, once I noticed how it uses the pacing of short fiction to disguise the violent reality at its center. “Cheri,” the third piece in Festival Days, is another nonfiction essay that reads like a short story, although unlike “The Fourth State of Matter,” it substitutes reportage for memoir. To create the piece, Beard interviewed friends and family members of Cheri Tremble, a woman with terminal breast cancer who sought a physician-assisted suicide. So many of Beard’s other essays are about unexpected and unwelcome twists of fate—illness, a spouse leaving, an apartment burning down—so it is no wonder she was drawn to the story of Cheri, who answers a terminal diagnosis with a final decision of her own.

The ease with which Beard mixes fact with fiction fits the subject perfectly. The real-life characters in the story seem drawn from literature, from the actual Dr. Kevorkian, to the perfectly-named protagonist who stares down her own death. Beard’s interviews with family members could only portray her life up until the moment that she said goodbye and closed the door to begin the procedure. From that point on, Beard lets fiction lead. There is the cold stab of a needle, and Beard illustrates Cheri crossing from life into death with the image of her slipping through the ice of a skating pond, down into the water. The image of the skating pond is pulled from Cheri’s past, as earlier in the piece we learned that in fifth grade Cheri did plunge through too-thin ice while skating, but was rescued. When Beard appropriates this real memory to imagine the coldness and mystery of Cheri’s death, the effect is stunning and seamless.

The essay “Werner,” about a single night in painter Werner Hoeflich’s life, offers another instance of the technique. Beard connects the eponymous subject’s memory of cliff diving in Oregon, to the figure of him tumbling through the air at a gymnastics meet, to the noise of the summer he spent working in a retread factory, to the essay’s actual subject: the night he saved his own life by leaping from his burning apartment building into and through the window of a neighbor.

This move, interweaving memories of the narrator that resonate with their current situation, is one example of the associative logic that drives all of Beard’s writing. In “Now,” an essay about preparing a craft talk for her university, Beard explains her works’ guiding principle of composition: “it’s simply thinking, focused thinking, with words attached to memories attached to images and the images linked to form the elusive, still-blurry idea at its core.” Even as Beard reveals her “one neat trick,” it does not at all cheapen its effect.

The final essay “Festival Days” connects memories of two different vacations that were each taken in response to a great upheaval in Beard’s life. Beard narrates the essay from a vacation home in Arizona where she has come to recuperate after her husband left her for a younger woman. In a sublime moment, eating chips on the roof with her friend Mary, Beard offers a perfect gloss on friendship, naming “that particular joy of knowing another person’s past and present so completely.” In light of the entire collection, the line also captures what is so lovely about Beard’s writing, especially the pieces “Cheri” and “Werner,” which are drawn from the lives of others.

So it is ironic that in sum, “Festival Days” communicates this joy less so than other pieces in the collection. In addition to the trip with Mary, the essay also tells the story of a voyage through India that Beard makes with her friend Kathy, who is terminally ill. The essay captures Beard’s own grief, but what’s missing from the essay is a precise picture of the friend she’s losing: we never learn what type of writing Kathy does, for instance, or what drew her to India in the first place. Moreover, Beard’s gaze, carefully calibrated to the natural beauty and social tensions of American college towns, wavers when it comes to rendering India. The descriptions too closely resemble comments that uncomfortable Americans write on travel websites: the animals on the street are starving, the men are intimidating, the women are beautiful. I wondered, when reading the essay, if the two problems were related: if Beard was unable to explain what their last trip meant to Kathy because she failed to see India through her friend’s eyes.

The misstep of “Festival Days” is only worth mentioning because it is the one previously unpublished piece in the collection. Otherwise, the collection as a whole is remarkable. In other collections, I often find that in bringing different forms together, an author sacrifices the cohesion of their book. In Festival Days on the other hand, the disparateness of the pieces highlights the consistency of Beard’s style. Beard renders the boring and the everyday in the same vivid language as the violent and the truly awful. In the end, Beard’s writing bounds over literary questions of fiction versus nonfiction. Her essays instead resemble forms plucked from life itself: eulogies, stories told around a fire, narratives of our own lives that echo in our heads.

COLLECTION

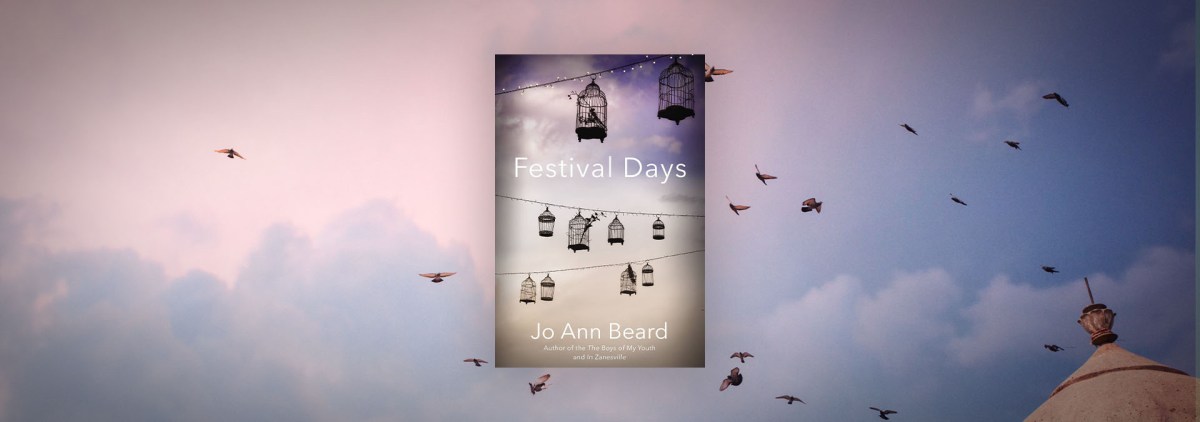

Festival Days

by Jo Ann Beard

Little, Brown and Company

Published March 16, 2021

[ad_2]

Source link