[ad_1]

Madame d’Aulnoy was a literary leader of late 17th century France—ahead of even Charles Perrault in popularizing the literary fairy tale. As Jack Zipes notes in his introduction to this new collection of d’Aulnoy’s tales, The Island of Happiness, Madame d’Aulnoy was the inventor of the term “fairy tales.” She used this form of storytelling then in ways authors still strive to adapt it now: to “vent criticism and at the same time project hope for a better world.”

Originally scattered across different chapbooks and novels, d’Aulnoy’s stories all derived from oral traditions she would have heard growing up. They’re full of lovers transformed into animals, exiled women on quests to prove or redeem themselves, and princes and princesses going to fantastical lengths to prove their devotion to one another. The stories are similar in theme and structure to other famous fairy tales that modern readers would know well, like “Sleeping Beauty” or “Snow White,” but these stories have a sense of humor about them, and a deep sense of ethics and justice for women missing from many other tales told by men around the same time.

In d’Aulnoy’s tales, a character’s gender or role in society is not always a huge indication of their role in the story. Characters define themselves on their own terms. Finette Cendron, for example, is a Cinderella figure who routinely forgives her unpleasant sisters, but she also has the opportunity to outsmart them in battle by chopping off the head of an ogress. The jealous queen in “Belle-Belle” is an antagonist who sends Belle-Belle on impossible quests, but we also see deeply into how she feels abandoned and rejected by Belle-Belle, and we feel sorry for her.

The stories are hyperbolic and dramatic, swinging through dozens of emotions and plot twists. There are stories within stories, and they often end in places wildly different from where they begin. This is part of what allows for such dynamic characters—there’s time and space for them to fill many roles, be many different things, over the course of a long and winding tale.

While we can celebrate this collection as being feminist for its time, it shouldn’t necessarily be heralded as a perfect lost work of art—d’Aulnoy includes casual racism in some of her jokes, suggests that an “ugly” woman is less of a woman than a beautiful one, and relies on a woman’s body to prove her innocence and womanliness, suggesting that some types of women are better than others.

In doing so, Madame d’Aulnoy upholds some of the traditional, convenient, and flawed morality of the folk tales she’s retelling. Yet she was radical in other ways: Zipes’s introduction includes heaps of helpful historical context, and he details that as a probable survivor of sexual violence, she was willing to criticize traditional patriarchal values of her society in her writing “by conceiving pagan worlds in which extraordinarily majestic and powerful female fairies had the final say.”

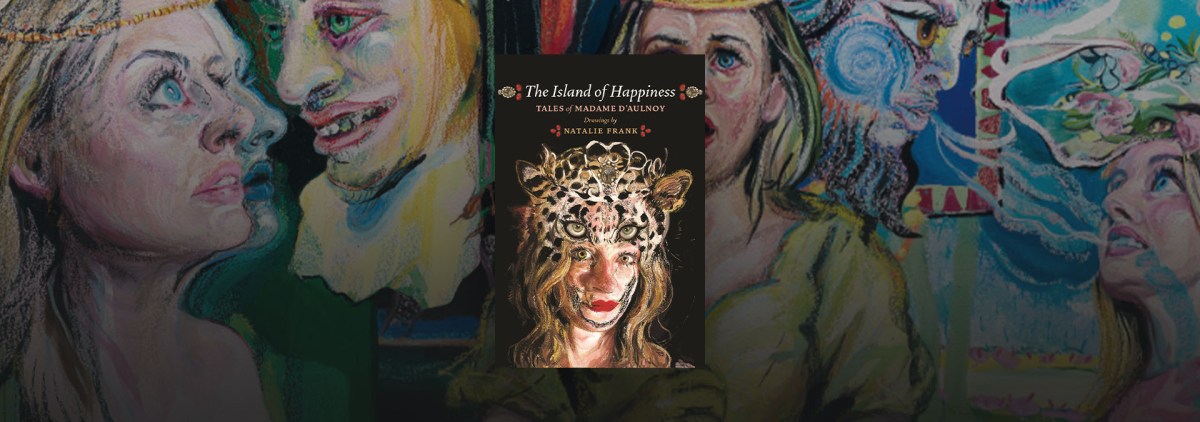

The new illustrations by Natalie Frank are another triumph of this collection, and they heighten the potential for d’Aulnoy’s radical stances. Frank’s women are larger than life; they’re clearly defined in a realist style while surrounded by surreal splashes of color and figures that blend into one another.

The illuminated tales are intense with color. Sometimes that vibrance is aggressive, such as in scenes when princesses are hiding from giants who want to eat them. And sometimes the vibrance is much sweeter, like when it lends itself to a magical animal menagerie where a heroine has lived blissfully for years, or in other such moments of connection, joy, and above all, love.

D’Aulnoy’s fairy tales are full of life and excitement that leads to the importance of finding true love, and the important distinction between true love and false love. She uses fairy tale circumstances to examine love deeply and ask questions about what love really is.

Like many other writers of fairy tales, d’Aulnoy places love on a pedestal, writing that “love is the greatest of all blessings. Love alone is able to fulfill our desires. All other sweet things of life become dull if they are not mixed with love’s attractive charms.” Yet she also digs into the complicated experience of love with more nuance than other fairy tales of the time.

Love serves as the center of the story, and the building relationship between characters is more significant. In The Green Serpent, the heroine must slowly come to know the serpent as a person and understand the depth of his curse, in a precursor to “Beauty and the Beast.” In “The Blue Bird,” the years in which the princess is trapped in a tower and visited by her transformed prince are passed with “tender discourse” as they actually get the opportunity to know one another. The blue bird at Florine’s window “counted every second he was condemned to spend in the shape that prevented his marrying her, and never was the termination of a sentence more ardently desired.”

D’Aulnoy’s lovers spend time together, sometimes centuries, and this is the foundation for what “true” love actually is. We learn that it must be faithful, honest, tender, natural, forgiving, and just.

This collection is as much about our remembrance and regard for Madame d’Aulnoy as it is about the tales themselves. The book makes a valued effort to place her within a historical literary context and celebrate her work while celebrating her as a person, as well as her friends, the women who sat in salons telling stories like fairy godmothers themselves. Their magic was in this ability to imagine: through fantastical tales, they could speak against immorality they saw in the world around them and instead create a utopia of love.

FICTION

The Island of Happiness: Tales of Madame d’Aulnoy

Edited By Natalie Frank

Princeton University Press

Published May 18, 2021

[ad_2]

Source link