[ad_1]

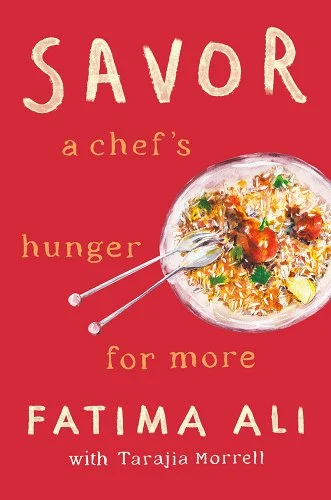

Fatima Ali was a rising star. A celebrity chef featured on the reality contests Chopped and Top Chef, Ali aspired to open the eyes and mouths of American diners to Pakistani flavors. But in 2017, at the age of twenty-nine, she was diagnosed with sarcoma, a rare form of cancer, and soon after passed away in 2019. She wanted a legacy connecting cultures through her food. Facing death, she chose to spend her time working with Tarajia Morrell on a final memoir, Savor: A Chef’s Hunger For More.

Ali was a writer too, and posthumously won a James Beard award for an essay in Bon Appétit Magazine discussing her diagnosis, battling the illness, and her hopes to eat parmigiana cheese in Italy. She never had the chance to live out her bucket list dream.

Despite Ali’s final eventuality, the memoir remains upbeat, highlighting the story of a woman who found the one thing she wanted to do with her life, and how she achieved it. Divided in three parts, the book moves first from her childhood with background on her family, then to a time when Ali exudes confidence convinced she has found her calling, and finally, describing her diagnosis, rapid decline in health, and eventual passing.

Although a memoir, many sections are told from the perspective of Ali’s mother, Farezah. These shifts complicate the narrative at times, especially toward the beginning. As the narrative expands, Ali’s voice grows stronger and more defined. Ferezah’s voice does provide background information to Fatima’s experience and later, as Fatima grows sicker, fills in meaningful details Fatima simply couldn’t know about. The interjection of Farezah’s voice also creates a parallel narrative illuminating her experiences as a daughter and a mother, and in the end, both Fatima and her grandmother are sick and dying.

Ali came from a life of privilege. Her family had servants and even following her parents’ divorce, access to wealth provided her with opportunities many ordinary people might not have. She was able to attend the Culinary Institute of America, earned a college degree through the school, and she and her family traveled the globe.

This privilege is never really discussed, even when Ali opens a popup restaurant in Pakistan. She acquires vegetables and ingredients from the farms of her father’s friends, bringing the farm-to-table restaurant concept to the country. If there is something missing from Ali’s reflections, it is the absence of recognition of how food, especially high end restaurant food, relates to class division. Her access to cooking, to culinary school, and a visa to America are points of privilege that go overlooked.

But partly what makes the book an enjoyable read is Ali’s lifestyle and insights into her life as a television celebrity chef. Her competence as a chef is illustrated not because she speaks about it, but through her successes. She operated a successful food stall at Brooklyn Smorgasburg, a frequent launching pad for up and coming chefs. On Chopped, she cooked “spiced chicken intestine purée with mis–clementine braised cabbage.” And in the second round of the competition, she succeeded even without ever tasting the pork she cooked, as Ali, a Muslim, refrained from eating the meat for religious reasons. Despite not tasting it, she went on to win the competition. She was then invited back to the Masters series of the show. She reveals how on Top Chef, contestants are kept secluded and isolated, their possessions searched for any unfair advantages, and all their reading materials confiscated. She lets us into that privileged space of celebrity chefs. It is the same quality that so many people found attractive in Anthony Bourdain, a peek into the lives of people through the lens of food.

Food is at the center of this memoir, from descriptions of holiday meals Ali cooked for her family, to the foods she ate as the guest of chefs from around the world. Both Fatima and her mother offer a look into the foods they ate. Farezah, for instance, lists of the dishes her mother would cook, like “spicy prawns with spring onions, thinly sliced beef with green chili and soy, a chicken fricassee, and the infamous ‘supgetti’ keema.” Even in death, Ali focuses the narrative around food. When her father and step-father arrive at the hospital for their final conversations with her, food is front and center, like the “Pakistani-style brothy Chinese Chicken with tons of masala and soy.” She understood the world through food and cooking, and the memoir captures that eloquently. She was confident in cooking, and relied on it even through her slow death.

One aspect of her life she remained at odds with was her sexuality. While in culinary school, she connected emotionally and sexually with a woman, seemingly the great love of her life, but her parents didn’t approve of the relationship. Her mother even suggested Ali should return to Pakistan after graduating, an implicit threat that she never followed through on. Still, the disapproval was obvious. Her mother warned her of same-sex relationships, something that Farezah never really fully accounted for even in her portions of the memoir, and suggested Fatima will eventually find a nice husband to settle down with. Ali, while a confident chef, and someone with enough conviction to launch new businesses and open restaurants, seemed to remain on edge when it comes to sexuality. She writes both about “my preference for girls,” but even hedges her self-descriptions. She had relationships with men as well, but she seemed far less confident about her sexuality than her ability to cook. Even in facing death, Fatima reflected uneasily, “I’m queer, I suppose, if must find a word to define my attraction to people’s spirits rather than the bodies that contain them.”Savor offers us a look into the short life of a person who wanted to accomplish many great things, worked extremely hard, and then suffered a great deal. Ali wanted her life to be centered around food, and wanted that food to create new ways of building relationships between the East and West, and in this memoir she has accomplished that.

NONFICTION

Savor: A Chef’s Hunger for More

By Fatima Ali with Tarajia Morrell

Ballantine Books

Published October 11, 2022

[ad_2]

Source link