[ad_1]

In her essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, Ursula K. Le Guin suggests that the “Hero story,” the one of conquest and knife-thrusting, is not the only form of storytelling available, even though it has become the dominant one. The alternative concept Le Guin offers is the bottle: “Not just the bottle of gin or wine, but bottle in its older sense of container in general, a thing that holds something else.” In this theory, the shape of our stories need not be spear-like, thrusting itself through fields and wars and families; instead, they can be much more: containers of anything we want to keep hold of. With this theory, Le Guin is able to find a place for herself within the human story for the first time; in this theory, her aversion to the bloody ways of Man the Hero is suddenly validated. “Wanting to be human too, I sought for evidence that I was; but if that’s what it took, to make a weapon and kill with it, then evidently I was either extremely defective as a human being, or not human at all.”

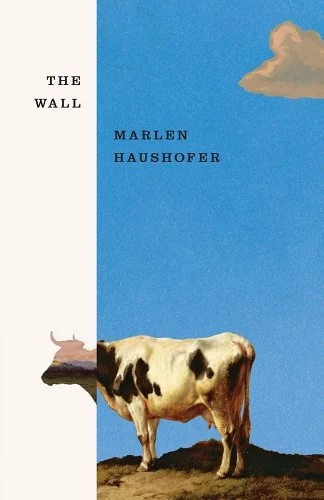

In the beginning of The Wall, a 1963 novel by the Austrian writer Marlen Haushofer, translated by Shaun Whiteside, we find the narrator reflecting back to a time when she was still a member of the wider world. “On the thirtieth of April the Ruttlingers invited me to drive with them to the hunting-lodge. I had been widowed for two years at the time, my two daughters were almost grown up and I could use my time as I saw fit. Not that I made much use of my freedom.” When the wall, a massive, invisible-to-the-eye barrier, comes down, it is in that hunting-lodge and the surrounding land that she is imprisoned.

Haushofer cauterises her unnamed narrator from society. In doing so, she fashions a kind of bottle in the center of the standard “Hero story” that Le Guin challenged. “[W]e’ve all let ourselves become part of the killer story,” writes Le Guin, “and so we may get finished along with it.” Haushofer intimates once or twice that the wall might be the result of an out-of-hand weapons development “that one of the major powers had managed to keep secret,” but the why and how of it all quickly becomes irrelevant. What matters is that the wall has exterminated all sentient life beyond it, and our narrator is now living in the wreck of the killer story.

It is this inversion that separates The Wall from other modern apocalypse stories. For example, Cormac McCarthy’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel The Road finds its dramatic line in societal breakdown and savage, man-on-man violence. By contrast, The Wall foregoes all human relations except for those that live in the narrator’s memory. Until the closing pages, the only acts of aggression committed are either because she must hunt deer for meat, or because the weather of the Alps itself is aggressive. Shorn of gunfights and threats of sexual violence – “The only enemy I had ever encountered in my life so far had been man” – the story is free to linger as the narrator adapts to her new environment: milking the sole cow left in the world, chopping wood, scything hay, migrating with the vibrant seasons, processing the Darwinian nature of wild animals. Walls instead of Roads; containers instead of spears.

What this leaves us with is an abundance of fine detail. The language, translated from German by Whiteside, is as practical and unadorned as the narrator herself. Any flourishes on display are reserved for philosophical inquiry, when she has the time to sit and reflect. Given over as the novel is to observation and patient recollection, the result is a voice both honest and generous. Haushofer’s eye for animal life is nothing short of miraculous, finding the kernel of their natures in one or two lines. Here, for example, of talking to dogs and cats:

“Later I told Lynx about it, for no particular reason, just so that I wouldn’t forget how to talk. For every ill he knew only a single cure, a mice little race in the forest. The cat listens to me attentively, but only as long as I don’t get all excited. She mistrusts even the merest hint of hysteria, and simply wanders off if I let myself go.”

It doesn’t take the narrator long to recognize that she is not unhappy about her new situation. Though she might be lonelier than ever before, the cats, dog, cow and bull she finds become her ragtag family unit where the roles of parent and child interchange and merge. It is in fact a much simpler and more rewarding family than she had ever been a part of. Those daughters she once had, who lie frozen somewhere in the city, are missed as the children they were, but not the adults they grew into. This of course initially sounds cruel, something she is well aware of, but, as she explains “I can allow myself to write the truth; all the people for whom I have lied throughout my life are dead.”

The import of this shouldn’t be glanced over or, if you’re inclined, dismissed as an example of a terrible mother, because this new truth is the core of Haushofer’s novel. Raised and educated and married in the midst of the Ascent of Man, where women are subdued into domestic artificiality, the narrator has never before had the opportunity to tell the truth. Indeed, it took the (near) extinction of the human race and all of its dreams of nuclear progress to finally allow her to begin something like a real life; a life in which she finally feels herself to be involved in her own story. The Wall is a fulfillment of what Le Guin’s essay called for: not a science fiction tied up in conquest and techno-heroes, but one grounded in realism, rather than mythology. “It is a strange realism,” Le Guin writes, “but it is a strange reality.”

Fiction

The Wall

By Marlen Haushofer

New Directions Publishing Corporation

Published June 21, 2022

[ad_2]

Source link