[ad_1]

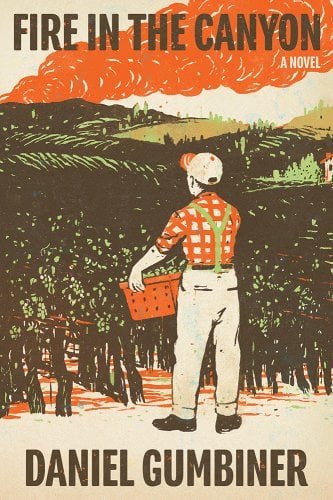

There’s something special about a novel that feels timeless, somehow older than itself from the moment it’s published. Such is the case with Daniel Gumbiner’s sophomore novel, Fire in the Canyon, which follows the recently reunited Hecht family and their surrounding community of California winemakers through the height of wildfire season. A big part of the novel’s staying power certainly rests in Gumbiner’s close attention to the fear of living under the constant threat of wildfires today, especially the emotional, financial, and political realities of having limited control in the face of unmitigated climate crisis.

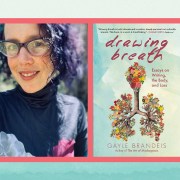

Gumbiner’s first novel, The Boatbuilder, was a finalist for the California Book Awards. He is the editor at The Believer. Over email, we discussed California literature, writers as characters, and the politics of climate fiction.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Aram Mrjoian

For many of us, climate crisis is a source of chronic tension. Can you talk about the genesis of Fire in the Canyon? How were you thinking about the constant threat of wildfires, both in terms of fiction and a lived reality?

Daniel Gumbiner

In recent years, I’d watched as worsening wildfires in California affected everyone around me, and I wanted to write something about that phenomenon. I definitely relate to feeling a kind of chronic tension, as you say. I think that is, in part, what the characters in the book are processing and responding to. How do you live in the midst of this kind of precarity? How do you plan for a future? I think these are questions we are all asking ourselves right now. In California, we are of course dealing with the threat of fire, but in Chicago, you have the erratic water levels of Lake Michigan, which could cause all sorts of problems (drinking water contamination, flooding, etc.). And you are actually also dealing with fire now, too, in the form of smoke pollution, which is a shocking and terrible development.

In any case, I knew I wanted to write something about what I saw happening around me, but I wasn’t exactly sure how to start. So I began talking to people, interviewing friends and family who’d had experiences with different fires. And one of my friends, who lives in Sonoma County, and who had lost all his barns in the Adobe Fire, started telling me about these different encounters he’d had with neighbors after the fire. And he mentioned all the ways in which the fire had altered his relationships with people. And that seemed like a compelling starting point to me. So I began looking at this question of: what happens after a fire? How might it set in motion transformations within a community? And this opened up a pathway to talk about a lot of different ways the wildfire crisis has affected people.

Aram Mrjoian

Climate fiction as a genre categorization has become increasingly popular, and I’ve seen a fair amount of essays arguing that all fiction written today is to an extent climate fiction, but in my own (limited) reading experience, one thing I’ve found is that much of this work is focused on a speculative future, whereas Fire in the Canyon feels alarmingly present. In your mind, what does it mean to write a realist novel about climate collapse as it’s being experienced and witnessed today?

Daniel Gumbiner

I like that idea that all fiction is climate fiction. How can it not be? The climate crisis shapes every writer’s worldview, in some sense. In terms of this book, one of the biggest challenges of writing in this style was actually getting out of the way. The material itself was so powerful and I think, at first, I overburdened it at times. In later drafts, I tried to pull back more, and let the simple yet intense dramas of the story shine through.

Another interesting part of working on this novel was the degree to which almost everyone I reached out to about it wanted to talk to me. I think there is a hunger for this kind of story. I think people want to talk about it. Like you say, we are dealing with this chronic stress in the background all the time, this ambient tension, and we rarely get to sit down and focus on it and talk about how we’re dealing with it. I think tapping into contemporary experiences helps facilitate that conversation. So that was in part what I was working toward in my approach. But I should say that there’s a ton of speculative climate fiction that I really like, and I think it’s a very useful frame to bring to the subject, too.

Aram Mrjoian

Related, and without spoiling anything, what was your approach to the ending of the novel? There are some really cool things that happen in terms of narrative structure.

Daniel Gumbiner

Thank you. Yes, that section actually came quite easily and quickly. I wrote it one night, in one long session of writing, and I barely revised it after that. It was more or less stream of consciousness.

Aram Mrjoian

Are there books you see Fire in the Canyon in lineage with?

Daniel Gumbiner

I think it feels connected to the work of Stegner, who is quoted in the epigraph. Claire Vaye Watkins and Jesmyn Ward were also big contemporary influences.

Aram Mrjoian

Fire in the Canyon digs into many of the quotidian aspects of California farm life and winemaking. What types of research went into showing how wildfires affect the day-to-day life of people living through and trying to keep their businesses alive during increasingly long and expansive wildfire seasons?

Daniel Gumbiner

I did a lot of research for this book, both when it comes to fire and winemaking. My research really varies: I’ll read books, read blogs, conduct interviews, go on road trips, you name it. For this novel, I read a lot of books by Stephen Pyne, who is the West’s foremost fire historian. I listened to oral histories of people who had been evacuated during fires. Most of the research I do doesn’t end up in the book. But I like to just drench myself in the subjects I’m writing about. My approach to research is to just try to take in a lot of information, and not think about what elements of it I’m going to use. I make it a focus to explore the subjects I’m writing about deeply, but when I sit down to write, I don’t usually have a book next to me that I’m consulting. This way, only the stuff that has really had an impact on me makes its way into the book. I find the researched material enters the work in a more organic way, with this approach.

Aram Mrjoian

Fire in the Canyon certainly has a political thread as well, one that reminded me of muckraking novels like Sinclair’s The Jungle, in the sense that we see how several characters become activists and negotiate the complexities of learning how to take action. What are your thoughts, perhaps both in this novel and more generally, about the politics inherent to fiction?

Daniel Gumbiner

This is a great question. One of the biggest challenges of the book was how to confront the political elements at stake when it comes to the subject of climate. Sometimes, it can be difficult to introduce the political into a story without overwhelming that story. But ultimately, I found there were natural ways in which that material could be broached—via the lived concerns of the characters—and those revisions felt like they really unlocked the book for me. It no longer felt like I was hiding some part of the story, or being coy about it. It felt like everything was more out in the open and therefore more emotionally true. So one of my revelations in the course of writing this book was that, sometimes, if you are dealing with a very political subject, the best thing to do is to lean into it head on.

Aram Mrjoian

You’re the editor of The Believer, a literary magazine that in my opinion regularly publishes some of the most innovative and memorable creative nonfiction coming out today. I’m curious about how your approach to editing in one genre influences your writing as a novelist and vice versa.

Daniel Gumbiner

I think editing nonfiction stories often involves a lot of the same techniques I use in fiction. You are working with fact, but you are often still sculpting a narrative, introducing a character, cleaning up a sentence. And that is all very similar to the editorial processes you go through with a novel. The biggest difference is that when you’re editing, you don’t have to produce anything: you’re wearing a more critical hat, and you’re pointing out ways the story might improve. When you’re writing, especially when you’re in the generative phase of a story, you have to turn that part of your brain off. You can’t be thinking too much about what’s wrong with the way you just introduced that character or you’ll stymie yourself pretty quickly. So when I write, I try to stay in a very nonjudgmental frame of mind, which is quite different from the frame of mind that I use to edit other people’s work. But then, once I begin to edit my own work, and return to that more analytical mindset, I do think my experience pruning and refining other people’s work becomes helpful at that point.

Aram Mrjoian

One of the central characters in Fire in the Canyon, Ada, is in fact a novelist. Of Ada, you write, “All of her work had some autobiographical element, though her later work had become increasingly less autobiographical.” With Ada’s character, did you see that as an opportunity to comment on the art of writing? Maybe your own experience? Additionally, the characters in this book are mostly active readers, and they discuss books, the newspaper, podcasts, etc., a kind of intertextuality or meta-textuality that feels intentional. Can you talk about that?

Daniel Gumbiner

In a lot of ways, Ada is quite different from me. But I did enjoy being able to work with a character who was a writer, and there are some things we have in common. Without giving away too much, one of the things she experiences, in the book, is one of my greatest writerly fears. Whenever you introduce a writer into a story, more possibilities for meta-textuality, as you mention, arise. But I felt pretty clear from the beginning that I didn’t want this to be a story about stories, so much as a story that involved a writer. This goes back, in part, to what I was saying before, about letting the gravity of the subject take center stage. I think the power of a story so often comes back to focus and balance. If I had drilled down deeply into the plot of one of Ada’s novels, for example, that would have pointed the reader’s attention in a certain direction, and away from some of the concerns that were more important to me. Of course, as a writer myself, who also knows many writers, it’s easy to draw from those experiences, and there’s a lot of material that could be added. So I tried to be thoughtful when it came to those elements, to include what felt compelling and important, without letting that material overtake the rest of the story.

Aram Mrjoian

In my mind, one of the perks of writing a novelist character as a novelist yourself is that you can consider certain aspects of the writing process. Your narrator notes, “Novelists had to remember things, to be able to recall vivid details. This was what made for great writing: to have all of your experiences at your command, and to cull from those experiences that which was most extraordinary, most telling and true. Over the years, she had somewhat disabused herself of this complex.” Do you find this true in your own experience as well?

Daniel Gumbiner

Yes, I think being able to harness concrete detail, however you do it, is important for good writing. Ada has always emphasized the role of memory in this, in part because her great fear about herself is that her memory isn’t good enough. I think, when it comes to our great fears, we tend to see them everywhere, and sometimes lend them more power than they deserve. I’m interested in those fears and perceived flaws, because I think they often drive our actions. But also because I think they are sometimes, surprisingly, the source of our greatest strengths. In Ada’s case, her bad memory is part of what actually makes her more present-minded, and gives her a unique way of moving through the world. There’s often something deeper, and not necessarily negative, on the other side of a supposed weakness in character.

Aram Mrjoian

Okay, last question. In his blurb for Fire in the Canyon, Tommy Orange begins, “I have felt for a long time like we need more California novels.” Is this a sentiment you also felt when writing? To you, what does it mean to have written a California novel?

Daniel Gumbiner

I do think that California, having been at the intersection of many cultural and historical movements, especially in the 20th century, has a unique character, and any novel set here, is in some way grappling with that character. I also think it occupies a really powerful place in the national imagination: it’s sometimes the great, gleaming future and other times the godless apocalypse. Ultimately, I think, it is a place characterized by experimentation. And experimentation can be exciting and also scary. This book depicts a kind of radical experimentation, in the later stages of the story, and I think that narrative thread, and the motivations of the characters involved, are definitely connected to the setting of the book.

FICTION

Fire in the Canyon

By Daniel Gumbiner

Astra House

Published October 3, 2023

[ad_2]

Source link