[ad_1]

The thing about longing is that it could take any form, really. Though vastly different on the surface, everything from going on walks or reading poems, to forged marriages for the sake of securing permanent legal residence, skipping meals, or crossing borders can be powered by an ineffable call towards something, someone, that emanates from the heart. Anything and everything can trace itself back to a desire that is born out of absence, a yearning to bridge a distance.

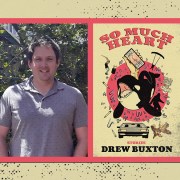

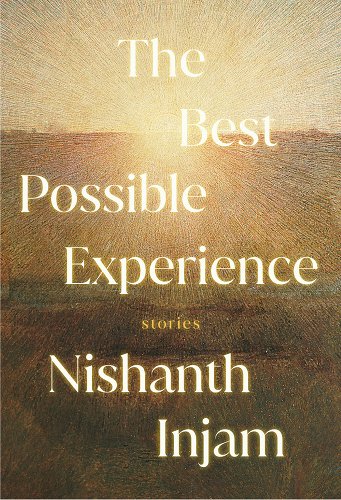

Longing is at the heart of the stunning debut short story collection by Nishanth Injam, The Best Possible Experience. Many characters—all of them either living in India or migrants to the United States from India—are in precarious situtations, trying to scrape by, scrap together money or a relationship, sometimes both. But the story behind the circumstances these characters find themselves in are stories about love, or the places that love can take you; they’re stories about desire, sometimes misunderstood, but nonetheless felt and pursued; they are stories about relationships and commitment. The Best Possible Experience is not just a story collection about immigration or immigrants, but about our capacity to feel, to tap into the deepest parts of ourselves, and an exploration of what we find in those depths.

I met with Nishanth at a coffee in West Loop earlier this year to discuss not only his book but his approach to writing in general, his relationship to himself and his sense of place, and writing through grief. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Farooq Chaudhry

How did you become a writer? I’d love to hear how you started because I know you started writing when you were a software engineer, and you still work as one.

Nishanth Injam

It’s been a long journey. I wasn’t much of a reader or writer growing up. I read very few books. I had this Tolstoy short stories collection at home and there were definitely some others, but the family emphasis was on getting into one of those technical schools [in India]. And so that was my entire focus.

I think when I was about to enter undergrad, like everybody, I just did computer science without thinking because at that point I didn’t even I didn’t even know what to do. I knew [computer science] wasn’t my thing, but that’s what you do anyway, because once you’re in a program, you don’t really change it. I knew my family was sort of in a precarious financial situation and I wanted to be able to contribute. And I knew that if I did a master’s degree in the US, I would be able to send money home. And that’s factored into my thinking a lot. So I did a master’s in computer science in Philadelphia.

But then I knew I had this moment of realization, the moment I walked out of the airport, or even before at the immigration center when the officer was talking to me, and I wasn’t really struggling to understand him. I mean, there were some words that I could pick up. But it was not just words. It was the way he was speaking to me. I immediately had the sense that I had made the biggest mistake of my life.

Farooq Chaudhry

In what sense?

Nishanth Injam

It was not because I wouldn’t be able to understand and, you know, sort of get myself familiar with the way people speak and all of that. But it’s just that when you grew up in a country that you call your own, you’re intimately familiar with the way people speak. There’s a lot of cultural history that you absorb from a certain place. I grew up in a small town in South India. And I didn’t definitely never listened to any pop music. So there’s a lot of cultural references that I absolutely had no idea about. And not only that, just the way like, you know, if someone is smiling at you, what does that mean? In India, all of those gestures have a different meaning. And, you know, you don’t exactly know where somebody was coming from.

Back in India I would be able to speak with someone and then intuitively understand where they’re coming from and what they might want from me. So that’s a skill that I felt like, that I gained after many years in India. So it felt like it was just going to be life with four senses instead of five.

So even as I was doing my masters and going through all of that, just trying to get through, I knew I hated what I was doing. I wasn’t remotely interested in it. I knew pretty quickly that it wasn’t my thing. But then I knew I had to get through, pass, get a good job. I had this loan that was like 15% interest rate. It was just crazy. So yeah, it was difficult. There were times when I skipped meals and all of that. But I think what I was not prepared for was the level of loneliness and the amount of loneliness I would feel and how crushing it would feel.

Sometime around 2014, I graduated and got a job at the Chicago Tribune. I used to walk across Michigan Avenue and on Lakeshore just feeling so broken actually, just because I knew I would go to work, desperate, I’d really hate what I was doing. But then I knew that I was also on this visa, right? Like, I couldn’t just switch and find a different job. I mean, I was speaking in broken English at that time, you know, so it would be really hard for me to get another well paying job. And then what was I even qualified for? Nothing other than computer science. So I think I began writing around that point, out of this sense of desperation, as a way of creating this alternative world where I was freer, where I was closer to home, where I had, like, my previous self with me. It was a preservation mechanism, I guess.

Farooq Chaudhry

When you first started writing, to create this world or create this sense of refuge, what type of writing were you doing? Were you journaling? Or did you immediately jump into fiction? And how did you even know that building your own world was the path that you wanted to take?

Nishanth Injam

I didn’t even start with fiction actually, I started with photography. I used to take pictures of landscapes, usually sunsets. And I realized I was always looking for a certain moment when, for example, a light hits and turns grass golden, or some certain moment. I was basically recreating a moment that I had already created in my head. And then I randomly I took this creative writing class, just to try it out, with Stanford online. That class changed my life. Like the moment I took the class and when we were supposed to write a story for workshop and I wrote a story, even as I was writing it I realized that this was what I was meant to be doing. I had this immense sense of relief that I had found an outlet of some sort. From there I just never looked back. Like, I never doubted that I was going up the wrong track or something like that.

Farooq Chaudhry

What’s your relationship like with Chicago?

Nishanth Injam

I think I’m indifferent, to be honest. It’s just the sense that this is not my country, or this is not something that I will ever understand. It’s almost as if when I left India, I entered this abstract realm where places are not tangible, concrete things. It’s really hard for me. Like, I’m not attached to any specific place in the city, even after living here for so many years. Yeah. I just don’t have that same sense of reality.

Farooq Chaudhry

Is it the same now, even when you have a child who is growing up here?

Nishanth Injam

Yeah.

Farooq Chauhdry

So what does it mean for a place to be emotionally abstract? Like you don’t let it emotionally penetrate you?

Nishanth Injam

I’m not stopping anything penetrating me emotionally. It’s just that it doesn’t feel real. It doesn’t feel real. It feels sort of, it seems it sort of feels like I’ve been transposed onto into this alternative world where.

It also relates to how you perceive a place. Like for instance, in my town I know, for example, the street corner where you get sweets, or the street corner where I used to go to school or things like that, you know. So a lot of memories are anchored and rooted to the spaces. So when I moved here, I didn’t have any of that. So none of the places actually felt real to me. So even the memories I’ve made here, They still feel very ephemeral and very loose and slippery.

Farooq Chaudhry

Do you think that sense of transience impacted every aspect of your life—so not just place, but relationships, for example? Are you in a type of third-place in relationships, or when you’re engaging with yourself?

Nishanth Injam

I think so. I think I think it’s there. I think it has permeated every aspect of anything it’s, I think that’s true for every immigrant, you know. That sense of duality or multiplicity. I try not to—really, I try not to, especially in relationships—but I think it’s still there.

Farooq Chaudhry

What does it mean to try not to?

Nishanth Injam

I think just being attentive to the way I might carry nostalgia, or the way I think about the past, and like just trying to be more present in my current moment and not not give it a frame of reference with the past in any way.

Farooq Chaudhry

Would you say the experience of migrating comes with a loss that is irrecoverable in some sense? I know we’ve been getting at that same question in many ways, where loneliness is just this constant, and maybe not something that one could recover from?

Nishanth Injam

I think it’s salvageable in some ways but it’s still a loss. That’s the way I see it. Ilya Kaminsky said [in an elegy for Joseph Brodsky] that “In plain speech, for the sweetness / between the lines is no longer important, / what you call immigration, I call suicide.” So it’s like the death of a former self. But then years later once you sort of acclimate, then it becomes a rebirth. Like when you have a child and you’re growing up with your child like I am—my son is only one and a half, almost turning two—in a sense, growing up with him, in this new culture, in this new phase, it can be an act of rebirth as well. But given a chance, why would you want to live with only four senses when you can live with five.

Farooq Chaudhry

I felt that in your book a lot. So many characters were carrying a silent pain or a deep yearning. And the way immigrant stories are often told, it’s like we only get the rags to riches stories. Like, “look at this guy, he left poverty and came to America to work 80 hours a week, and he ‘made it.’” And we celebrate that stuff. But we tell those stories as if the only things that are intelligible are material comforts and material prosperity, but there are so many deep desires inside, so many meaningful relationships that are left behind or go unexamined. Was speaking to those silent desires a conscious decision?

Nishanth Injam

It was. I think it’s conscious in the sense that I knew I was going to do that. But it’s also something that I knew I couldn’t help but do. Because it’s like, why do we even make art, right? At least that’s the question I was posing to myself, like, why did I even bother? Why write any of this? Was it just because I was lonely and I didn’t have anything to hold on to? In the beginning, yes. At the beginning, it was great. I don’t have language for this, I don’t have a home, let me create a home for myself. And then at some point, it becomes more than that, it becomes an act of rebellion. To save something that is, well, let me build a home. Let me build a home that encompasses all of it. That makes space for somebody like me. Let me make a home that feels right.

And when I say that, I don’t just mean living in one country or another. Like for instance, just the daily grind of our lives, you know? I know that as a society, we’ve become very shallow. Like the Marxist philosopher, [Herbert] Marcuse, in his book The One Dimensional Man, sort of writes about how we’re conditioned to treat every desire that can immediately be accessible and converted into some sort of product as the only desire that’s valid.

So I was writing from a place where I was trying to rebel against that. I was seeing in art, in books, in life in general, the way that emotions are sort of kept at bay, and it’s become this shallow pool of water that you never really know or engage with.

Farooq Chaudhry

When it comes to speaking to various types of silences, silent desires, did you consciously see the connection between the silent pain of repressed sexuality and the silent pain of living a precarious life because your mother is sick back home and you have to take care of her? Or are each of these experiences different ones that you want to explore?

Nishanth Injam

I think there’s a degree of connection, for sure. In all of those stories, the depth of the pain or the feeling, the intensity of feeling that I’m trying to depict is very real, and I want it to feel very deep. And the reason I wanted that level of depth is because I wanted the book to be about a yearning in a sense. Not just about stories of the diaspora or stories of immigration, but also stories of yearning.

Like there’s this ocean in each of us. And most of the time we’re just coasting at the top. And I wanted to go to those deeper places because you cannot immediately turn them into products. Those deep places are from where you can actually actively rebel. It’s like, if you don’t have large bodies of water, Earth is going to collapse. It’s sort of like that. If you don’t have all of those ecosystems working properly, we’re just gonna continually erode.

Farooq Chaudhry

Do you feel like you were in touch with the depth within yourself in India, and then lost that connection here?

Nishanth Injam

Yes, I felt more myself when I was in India. For instance, even when I go back to India right now, the minute after I land, I just feel a sense of weight lifting off. I feel free. I feel like I can breathe. But at the same time, I don’t want to romanticize it because there are a ton of problems in India, right? Like there’s just so much wrong, there’s so much going on.

Farooq Chaudhry

How did you develop a sense of voice in your writing? And I’m curious, who did you read when you discovered this world of stories and of writing? Because I know you start with Calvino’s Invisible Cities in the epigraph of your book.

Nishanth Injam

After Calvino, I basically read everything I could find. Arundhati Roy has always been a north-star for me. Kazuo Ishiguro for his emotional scope. And I didn’t read as much contemporary fiction, I started with going to the classics first. So 19th century Russian literature, Anna Karenina, Dostoevsky. I couldn’t really connect with American literature for a long time. I couldn’t Hemingway—I just thought, what is this? I felt nothing. I think I’ve gained an appreciation for it after picking up more awareness and more historical context.. I was coming at it with Eastern sensibilities, and I didn’t quite know how the West operated. And so it was a case of me learning.

It was only when I went to Russian literature I could find a source of like, oh yeah, I get this—this speaks to me. I have to say, there are exceptions though. Toni Morrison. James Baldwin. I loved them. I think they’re probably the only two or three writers in America that when I first read them, I really got into it from the beginning. I don’t think about American literature the same way anymore though. It’s just that when I first started, I couldn’t really get into it. I think it has a lot to do with the sense of place and how America didn’t feel real as a place to me.

Farooq Chaudhry

Grief is a heavy sentiment in your writing, and we’ve also talked about your mother passing away during the second year of your MFA program. How has grief informed your relationship to writing?

Nishanth Injam

I didn’t believe in the power of words. I had all of these ideas about literature and how it would sort of inoculate people against grief, but it didn’t. I mean, they’re just words. It’s meaning-making at the end of the day.

Farooq Chaudhry

What made you think it was going to inoculate you?

Nishanth Injam

I thought, in a sense, because these stories were trying to ask all of these hard questions about, like, what’s going to happen when one day my parents aren’t here? Because my world would end if they’re not here in some capacity. So I’m trying to reach for answers to those questions when in the process of writing this book, and so I thought I was coming up with these answers. Clever answers or clever ways of making meaning that I will find relevant even after they might have passed.

But you can’t inoculate yourself against grief in any way. It just overpowers you. So basically I just started thinking, what’s the point of literature if it can’t help staunch my wound a little bit? I thought I was writing literature to help. Not to ease all pain, but as a way to stop myself from feeling like I need to kill myself. I thought I would have some defense mechanism. But then I realized all of the writing I did, it didn’t do that. It just felt like literature was pointless for a long time.

Farooq Chaudhry

Do you still feel like that?

Nishanth Injam

On some level. On some level, I’m still deeply skeptical. But then there’s still hope and meaning, and I think there’s literature that nourishes me. There’s literature that I find value in. But it’s still meaning-making, right? It’s choosing to derive meaning. You’re getting to a place where you think, okay, I need this meaning to exist. And so I’m gonna grab it, I’m going to attach importance to it, I’m going to make meaning from it. You know, it’s you positioning yourself to a place of greater security, not literature itself that’s doing that for it. And so I struggled through that. I mean, when people talk about literature having this power, books providing empathy, I don’t necessarily believe that. I mean… I’m not a cynic by any means. I just mean that if books were exactly what people need them to be, then more people would read books.

Farooq Chaudhry

I don’t know about that. How many people avoid what they need all the time? Does that mean they don’t need it?

Nishanth Injam

The way I’ve recently begun to think about it is that, internally, the way I think about myself is that I’m a shy, loving person. But if I’m a stranger, walking down the street, or just a casual acquaintance, then you’ll see me but you’ll also possibly see a shell or a protective layer over me. I’m more conscious these days reading and writing to figure out how to open myself up and actually be a more loving person to others.

FICTION

The Best Possible Experience

By Nishanth Injam

Pantheon Books

Published July 11, 2023

[ad_2]

Source link