[ad_1]

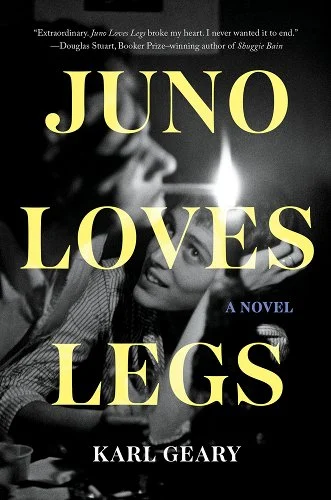

Near the beginning of Juno Loves Legs, Juno’s mother—a poorly paid seamstress struggling to make ends meet for her two daughters and alcoholic husband in a Dublin housing estate in the 1980s—modifies her own wedding dress so Juno can wear it to her confirmation. When her mother is killed in a sudden accident before the confirmation occurs, Juno dyes the dress black for the funeral. Hanging up to dry, dripping dark liquid, the dress seems “to sway as if to music, one of the old songs; its final memory of a first dance.” The transformations of the wedding dress depict, in microcosm, how Karl Geary’s sophomore novel flirts with and then darkly subverts the marriage plot, killing off the nuclear family in an attempt to remake it, with a difference.

In school, Juno meets Seán, whom she nicknames “Legs.” This christening marks Legs as an outsider to his Catholic community, like Juno herself, whose mother made the “unusual” decision to name her after a pagan goddess rather than a Christian saint. Juno is the goddess of marriage; as a Roman rendition of a Greek deity, she signifies a concept of marriage already in translation. The new moniker Juno gives to Legs is also an indication of the synecdochal voice in which she narrates their story. Contrasting herself with her parents, who often fight, she says, “they were two mouths and I was their ear.” Her preference for synecdoche suggests her confined perspective, reflecting her sense that “the world was another, a vast other, in which I’d occupied a narrow and separate part.”

Right away, Juno feels like Legs is the part she is missing. The two are halves of one whole, their difficulties inverted images of each other. She always has dirt underneath her fingernails and her lawn is cluttered with broken cars that her father has been commissioned to fix. Legs’ hands are too clean and his mother covers their furniture, floors, and banisters in plastic sheeting. Juno has feelings for Legs and dreams that she will be with him forever, but only later realizes that he is gay. The friends are separated when Legs violently attacks a priest who subjects him to homophobic abuse and ends up incarcerated, first in a juvenile detention facility and later in a boarding school, while Juno is thrown out of her house following one of her outbursts of anger and grief and learns to survive on the street. When they meet again in the city center as adults, they form their own unconventional household, for a time.

As Clair Wills has argued often, Irish fiction tends to use depictions of intimate familial abuse to allegorize large-scale institutional abuse levied against Irish society by the Catholic Church and a theocratic post-Independence state. “The modern Irish novel,” she writes, “seems dedicated to insisting on the ways in which sexual violation in Ireland is not, or not only, done by one individual to another, but the force of an entire culture.” In Geary’s novel—set in the decade before the Celtic Tiger, with the Church beginning to lose its influence but not yet fully relinquishing its control over possibilities for living—the characters’ fractured families and sexualized precarity are not accidents; their individual pain is shaped by systemic social and economic oppressions that harm women and gay people in particular. Still, some of the accumulating miseries (poverty, assault, addiction, secrecy, illness) feel like old tropes. Although this is a historical novel, it might have spoken more directly to contemporary concerns, rather than framing a bleak past as merely, in Joe Cleary’s terms, “a negative validation of the present.”

The plot of Juno Loves Legs is less a progressive coming-of-age narrative than a swirling eddy that recursively flows back on itself. Juno grows up and chooses a new family, but she doesn’t avoid inheriting the trauma of her former family. The final chapters echo with images and characters from the beginning of the book. Legs is dying of complications due to AIDS and Juno finds herself back where she started: alone, in the neighborhood where she grew up, having tea with the librarian who was the only adult to show her kindness as a child. As its title suggests, Juno Loves Legs is an affecting redefinition of love—but recreating the family, even in unexpected forms, doesn’t save the characters in the end.

FICTION

Juno Loves Legs

Karl Geary

Catapult

Published on April 18, 2023

[ad_2]

Source link