[ad_1]

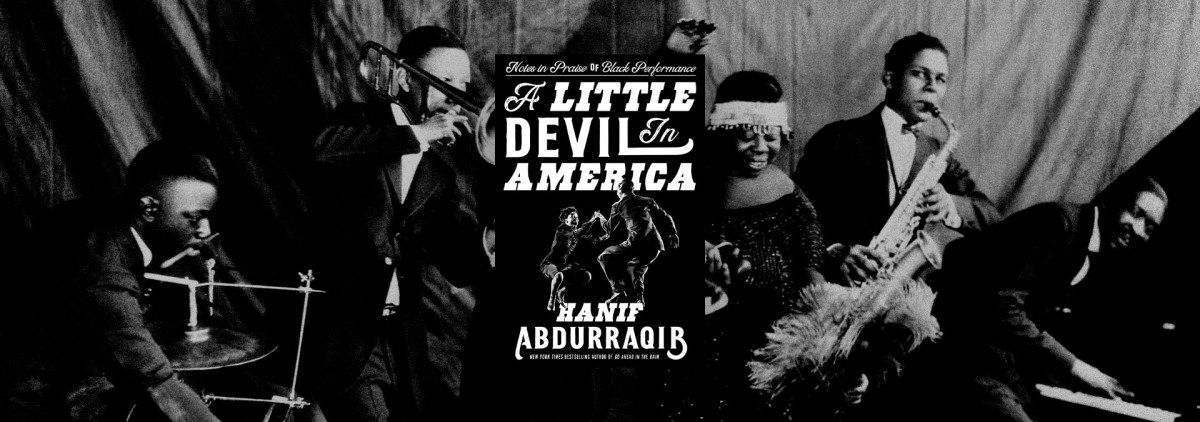

A Little Devil in America: Notes in Praise of Black Performance, features Hanif Abdurraqib’s considerable talents as a poet, essayist and thoughtful social commentator. Reading this book reminded me of listening to the late-night DJs of my youth—I especially remember Alison Steele, the Nightbird—who used songs as the starting point to improvise a jazz solo of murmured conversation and mellifluous contemplation. Abdurraqib also belongs in the special order of those who magically entwine musicality, voice and narrative in the liminal place between sleep and wakefulness where all is possible, and temporality is fluid.

Abdurraqib uses a repetitive literary motif to organize the book, much like there is in modern dance, jazz or poetry. There are four numbered sections entitled “Movement,” each one starting with a different essay entitled “On Times I Have Forced Myself to Dance.” Stylistically, the repeated title points to the many stories that can be told on the same subject, but it also reflects Abdurraqib’s compelling ability to innovate and riff off the same introductory notes.

The first essay starts with the excesses of dance marathons in the early 20th century, which tested the limits of physical endurance and later provided an outlet for a populace devastated by the stock market crash and subsequent Depression. Abdurraqib segues into the relative lack of Black people in these often brutal performances by noting: “After all, what is endurance to a people who have already endured?” Later he comments on the advent of shows like Soul Train, which celebrated youthful skill and joyfulness: “A people cannot only see themselves suffering, lest they believe themselves only worthy of pain, or only celebrated when that pain is overcome.”

Throughout this collection, Abdurraqib underscores the freedom and the power of choosing to be jubilant in the face of pain, oppression, and others’ opinions: the way those young people used their few minutes on the dance line to express themselves in the moment, and through the videos, eternally.

In both his poetry and essays, Abdurraqib is especially brilliant at contemplating our humanity through the lens of the arts, and each of these essays has a sonic flair, as if prose can’t contain his innate musicality. Another hallmark is how seamlessly Abdurraqib inserts moving personal experiences into his contemplations of Black life and performance. In one instance, he expertly weaves musings about death practices across religions to the loss of his mother, and later to the homegoing of Aretha Franklin, offering a reminder that a funeral is also a celebration of life, a time where the person is lost to us corporeally, yet still alive through our rituals. Who among us hasn’t experienced the aching clutch of “holding on to the memory of someone with two hands and saying I refuse to let you sink.” How resonant this is in an era of great loss and distance.

He refers to a “multitudinous nature of Blackness,” and one can say the same about this collection, which is somehow both deeply personal and thematically large enough to encompass a variety of philosophical and political issues. This is an especially rewarding kind of memoir, cultural criticism and temporality, and Abdurraqib skillfully and organically combines all three, making this collection of the moment and of many moments, past, present and future. In these pages, Carlton from Fresh Prince is in the same space as Josephine Baker as Sun Ra as Don Shirley, and as the exquisite Merry Clayton, along with many of the loves and friends and family in Abduraqqib’s life. They are all alive in Abdurraqib’s memories and appreciation, reminding us of the necessity of remembering and praising all of our own intimates. The act of gratitude, the act of love, upends time and loss.

Abdurraqib’s book is a dance in literary form; he moves with us and entices us to move toward him, to engage in one of the most intimate of social interactions: “I am in love with the idea of partnering as means of survival, or a brief thrill, or a chance to conquer a moment.” And a magnificent partner he is, both leading and leaving enough space for the reader to inhabit the experiences he creates in his exceptionally engaging prose.

In A Little Devil in America, Abdurraqib’s fascinating research into historical customs and rituals is deftly married to sometimes achingly personal revelations, yielding a singular poetic rumination about the self and society. He effectively uses popular culture to illustrate the repeated attempts to diminish and outright erase Black people, and, more important, elevate their undeniable contributions to the best of America. He also appropriately calls many of us to account: “There can be no solution without acknowledgement, and so I don’t want anyone to watch this movie and consider themselves clean. Everyone else will have to earn it.”

After completing this collection what remains in my mind and heart—a beautiful echo—is that subtle yet mighty secondary title, the praise and celebration for Black performers and Blackness overall. There’s much joy in this book, as there is in the lives that Abdurraqib explores, including his own. We need that joy, that celebration, this book.

NONFICTION

A Little Devil in America: Notes in Praise of Black Performance

By Hanif Abdurraqib

Random House

Published March 30, 2021

[ad_2]

Source link