[ad_1]

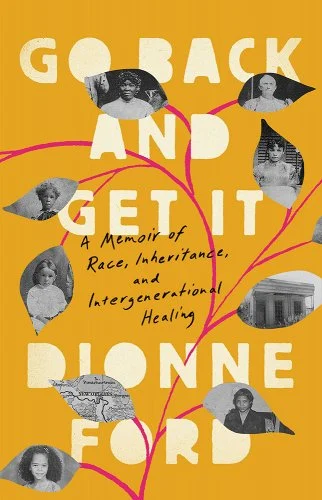

Research has shown there’s a hereditary component to trauma—its effects can be passed down in utero, etched into our DNA. When I first came across the research, I thought about this country’s horrific history of genocide and slavery and wondered about the implications beyond a single generation. What are the effects on the descendants of people who experienced these horrific, violent traumas? Dionne Ford dives into answering that question through the lens of her own experience in Go Back and Get It: A Memoir of Race, Inheritance, and Intergenerational Healing.

From the opening pages—which include an old photograph, a family tree that traces back to Ford’s great-great grandmother who was enslaved, and an author’s note about the things she relied on to write the book: her memory, others’ memories, her journals, and research—it’s clear how much, both the physical act writing and the emotional toil doing so must’ve taken, went into this book. As those in social work or recovery know, healing can be a painful process, yet Ford shares her journey with thoughtfulness and grace.

Structuring such a book seems tricky; Ford divided chapters thematically—a craft decision that works extremely well. The prologue begins, “If you are going to look for your enslaved ancestors, you will have to look for the people who enslaved them,” and that tension carries throughout the book. Ford, who has two daughters with her (white) husband, and a grandfather who, she once wondered, if he might have been white, explores the complications of race in her own family throughout the book. She reckons with her own traumatic past as a survivor of sexual violence by a family member (who remains unnamed, including how the two are related), her subsequent struggle with alcoholism, her path to recovery, and the research she did to trace her family’s history back to her great-great grandmother, Temple “Tempy” Burton, an enslaved woman who was given as a wedding gift to a Louisana cotton broker, whose youngest of six children was Ford’s great grandmother.

It’s the photograph of Tempy which appears in the book’s opening pages that leads Ford on this voyage of discovery:

“If you are going to recover the rest of your enslaved family, you will have to get a PhD in the history of their enslavers. It takes the average student 8.2 years to earn a doctorate degree, so you will need to practice persistence and patience. You will also need to forgive yourself. Daily. Spending this much time with people, even people who are dead, even people who enslaved your ancestors, will inevitably open you to their humanity as you consider their brutality. Forgive yourself for laughing when they poke fun at each other in their letters, for your heart pangs when they lose a child to yellow fever, or your awe at the care their descendants took to preserve their two-hundred-year-old diaries, correspondences, and hand-drawn maps of their land grants. Forgive and proceed.”

Ford’s willingness to stare down her, her family’s, and this country’s painful history makes this book extraordinary, alongside her openness about her path to healing—one that included a wide range of therapies, lifestyle changes, and recovery meetings. These therapies are necessary to deal with the post-traumatic stress she endured, and yet are never covered by her insurance. She shares how child abuse is the most costly public health issue in the United States, according to the results of the Adverse Childhood Experiences study, and how one of the researchers behind the study believes if we eradicated childhood abuse in this country, we could more than half the prevalence of depression, reduce alcoholism by two-thirds, and suicide and domestic violence by three-quarters. Such statistics, and her tracing murder victim Alton Sterling’s family’s history back to who his ancestor’s enslavers, too, make this book a stunning feat and important enough to call it “required reading.”

Yes, a book that deals with slavery and trauma isn’t a light read. Too many (let’s face it—white) people avoid salient books about race because of the heaviness of the topic. But like any healing, personally or collectively, one must confront the pain before it can lessen. Perhaps our country’s roots are too atrocious for a full recovery, but Go Back and Get It shows us that healing is possible, at least on an individual level. Not easy, not without pain, but achievable. And if individual healing is possible, perhaps collective healing can follow.

Dionne Ford’s debut is one we should all be reading. In Ford’s words, while “Some people say, ‘Forgive and forget.’ I say, ‘Remember and recover.’ Re-member. Put yourself back together again and again.” We’re so lucky to have Ford’s beautiful book as a roadmap for our country’s much needed recovery.

NONFICTION

Go Back and Get It: A Memoir of Race, Inheritance, and Intergenerational Healing

By Dionne Ford

Bold Type Books

Published April 4, 2023

[ad_2]

Source link