[ad_1]

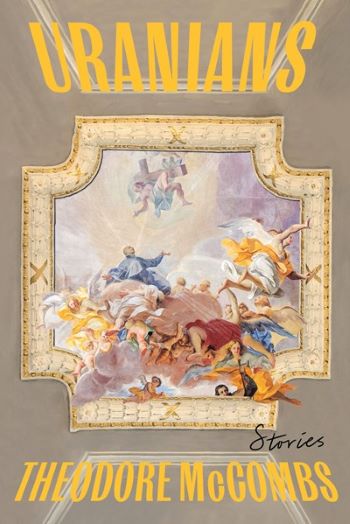

Theodore McCombs’s debut collection, Uranians, is a remarkable achievement, a polished and varied set of stories: speculative, queer, and cerebral. The entire set shines on a prose level, from the off-hand description of a climate-ravaged San Francisco with “Hail, thick as eyes” in “Laguna Beach” to the repeated floral metaphors of the title story: “Gardens helplessly retching color in a jury-rigged extrasolar spring” and, bending to shifting gravity, “Old trees will grow like parentheses.” There’s a deep well of thought under these stories, careful consideration that flashes into sudden vivid imagery and cutting insights—sometimes mournful and often powerfully, strangely persistent.

The collection’s opening story, “Toward a Theory of Alternative Lifestyles,” a masterful brief character study, flirts with multiverse ideas, but primarily as a thematic foil to the tension between queerness and squareness in the main character’s desires. It’s something of a relief to not dive into yet another many-worlds story—though I was tickled by “hypnalectronica,” an underground music genre that literalizes “trance” into something like “reality shifting”—and the fantastic elements here are a sparkling offset to the story’s humane and bathetic core, reminding me a bit of Cortázar.

In “Talk to Your Children About Two-Tongued Jeremy,” an educational AI traps a young boy in a maze of abuse. The story’s genius is not so much in the cautionary (and topical) technological angle as in how it demonstrates that these structures of expectation and control are nothing new; McCombs also deploys the best use of the first-person plural I’ve seen since Headley’s The Mere Wife. “Laguna Heights” is a meditation on memory suppression, sort of a corporate legal twist on Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind in a Ted Chiang-like mode, while “Six Hangings in the Land of Unkillable Women” is an early twentieth century period-piece where women have become ambiguously invincible—a surreal and effective look at the psychology of resentment, how privileged actors can only read others’ empowerment as their own disempowerment.

The opening stories are excellent, but Uranians, the novella that anchors the collection, is something else entirely—a quiet series of explosions, echoes, and harmonies, the kind of story that raises goosebumps and leaves a humming silence of narrative afterglow. It’s the most classically science-fictional of the collection: a generation ship heading to another star. And it uses that structure for a profound and astonishing story of queer individuality and community. A one-way reconnaissance trip to a hopefully-earthlike planet, the mission selects only crew who don’t have or want children, who are willing to give up all normalcy for something strange and new. As the narrator puts it: “can you think of a demographic that might end up, hmm, overrepresented in that collection of scientists, thinkers, and artists…?”

I must admit that the generation ship (a space-ship that takes centuries to reach its destination) is a trope I was ready to be done with. Literal and metaphorical vehicles of colonialism, “Planet B” enablers ready-made for kleptocratic grift, and oddly perfect settings for the most interminably juvenile kind of social critique, I was thrilled when Kim Stanley Robinson put a stake through their hearts with his 2015 novel Aurora. I shouldn’t be surprised that they didn’t actually die—what trope does, these days—and I am still reeling from how good Uranians is. It’s not just that it overcomes and addresses the problems of its construction—though it does—it’s that the novella plays with the potency of the metaphor, the imagery: how that setting magnifies and dramatizes the fundamental premises of life on this much larger generation ship, of our own one-way missions. Surrounded, detached, in measureless oceans of space, to steal a phrase.

One of the most laudable aspects of Uranians is how, within its modest length, McCombs uses time itself as a subject, as medium and muse. Many novels struggle to capture a single character changing; here, an entire cast metamorphosizes—and think of that not only in terms of frogs or butterflies, but of stone, the changes wrought by heat and pressure. Mortality is one looming time-element, as characters age, as communities come under threat, as Earth itself reels from disaster. But just as vital is continuity—the dense tapestry of interconnection gestured at in the novella’s frequent and evocative allusions—and a keen and gentle feeling for the weirdness that inheres between people, between generations, the way that disagreement and even mutual unintelligibility are part of personal and communal vibrancy.

Giuseppe Verdi’s operas and writings are a major touchstone, and the novella is strung through with references to art and theory. It’s far too weak to say these “add color;” these are the strings (or the ocean) coming in, these are like the keisaku striking the Zen practitioner, refocusing. The novella’s title is drawn from the work of Edward Carpenter, early gay activist and utopian; references throughout range from Eliot puns and elegiac Leaves of Grass-drops to Jack Halberstam excerpts on queer temporality and a line or two from Robert Duncan that hit me like a truck. It’s a remarkable, mesmerizing approach, using the very detachment and isolation of the setting to underscore a complicated and contradictory knotwork of exile and history. It’s worth tracking down, incidentally, Sarah Pinsker’s “Wind Will Rove” (which McCombs mentions in the acknowledgments) and Robinson’s collaboration with Marina Abramović for “The Hard Problem”, both of which are contemplating related issues through the lens of the generation ship.

McCombs does a good job not hitting us over the head with the ship’s name–Ekphrasis–but it’s well-chosen, and don’t let my praise for these allusions lead you to think this a work without character or plot. Despite its brevity, there’s a feeling of depth to the cast, their loves and concerns and conflicts—butch biologists, transgender priests, astronomers and engineers and philosophers. Arrigo Durrante, the central character, is fascinatingly and stealthily drawn, an almost cartoonish man in third-person who is suddenly grounded in first-person sections. As the decades of the story progress, he becomes—not concrete, not fixed, but more legible, more substantial. His relationships allow us a much broader window on the voyage, and while Uranians is rich with variously-expressed theories of queer ontology, Arrigo’s flat rejection of glib evolutionary explanations is still a rousing one.

One of the dangers of reviewing collections is that it makes one want to list: there’s simply too much here to summarize. Wonderfully crafted, texturally rich, the stories in Uranians have the kind of realism you only get with a little distance from reality—a thoughtful and splendid experience.

FICTION

by Theodore McCombs

Astra House

Published on May 30, 2023

[ad_2]

Source link