[ad_1]

Creating a fresh playlist of such a critical voice in modern American poetry is both a significant challenge for the editors and a satisfying reward for us. The Essential June Jordan, edited by Jan Heller Levi and Christoph Keller, is a generous collection which samples poems—some unpublished—across decades, making one distinctly aware of how important Jordan is to our current discourse. The most indispensable poets—and she is easily on that list—are both of their time and oddly prescient, and that is proven repeatedly throughout this collection.

What sets this book apart from others that try to capture the career-long portrait of a singular author between two covers is the editorial decision to present the work in an achronological manner. The thoughtful siting of the poems in such a fashion—in order to place “the June Jordan of then and the June Jordan of now, together”—is akin to the role of a talented director. These poems indicate both the intentions and imaginations of the editors and encourage readers to do the same. When the output is as robust and unbound by time as June Jordan’s poetry is, such experimental curations are both welcome and possible. This may not be the definitive compilation of Jordan’s work, whatever that might be, but it is decidedly a necessary one—and one that will rightly urge readers to seek out more of her work.

The core of Jordan’s work is deeply political, in the public sense of the word, and personal: in her hands, the two concepts are braided together, separate yet bound in intent. To be human in her times, in these times, is as much of a public act as a personal one.

“A Short Note to My Very Critical and Well-Beloved Friends and Comrades” is worth posting in its entirety, because it’s as fresh now, in both our polis and our public discourse, as it was forty years ago when it was first published:

“First they said I was too light

Then they said I was too dark

Then they said I was too different

Then they said I was too much the same

Then they said I was too young

Then they said I was too old

Then they said I was too interracial

Then they said I was too much a nationalist

Then they said I was too silly

Then they said I was too angry

Then they said I was too idealistic

Then they said I was too confusing altogether:

Make up your mind! They said. Are you militant

or sweet? Are you vegetarian or meat? Are you straight

or are you gay?

And I said, Hey! It’s not about my mind.”

The craft of “A Short Note” is beyond its striking content: look at the form Jordan used to structure her lines and add nuances to the powerful language. It’s a swinging hammer of repetition without punctuation; the accretion of the “then they” with the “too,” all of which imply the never-enoughness of the individual, while simultaneously boxing them into an unreasonable either/or construct. Yet at the conclusion, the poet literally takes a step away from the unending wall of external judgment, starting a new sentence, her own verse, her own statement of self that denies the power of the masses to sway her.

Jordan is as philosophical as she is linguistically thrilling. A number of these poems are in response to or inspired by others, and these conversations are indicative of the editors’ commitment to engage the reader in conversation with the poet, who through these pages is still with us, with profundity and playfulness to share. This is delightfully evident in selections from Last Words from 2001, such as “Poem for Siddhartha Guatama of the Shakyas: The Original Buddha:”

“You say: “Close your eye to the butterfly!”

I say: “Don’t blink!””

Or from “Shakespeare’s 116th Sonnet in Black English Translation:”

“Storm come. Storm go

away

but love stay

steady

(if you read or

you not!)

True love stay

steady

True love stay

hot!”

The oft-quoted Shakespearean original, which starts with “Let me not to the marriage of true minds / Admit impediments,” has been recited at many a wedding celebration, to be sure. Jordan’s revisal should become a new standard. So, too, her alterations subtly underscore the living nature of language. Though there are universal emotions we share regardless of our era, the way we express ourselves does and should change to reflect our times and experiences.

In his thoughtful afterword, the acclaimed poet Jericho Brown writes, “The legacy of June Jordan is a gift to us in that it allows another opportunity to think not only about what poems are, but also about what poems can do. Can a poem love you?”

The poems in this collection represent—employ—a vivid and powerful welter of emotions that they share freely: righteous rage, empathy, praise, deep sorrow, passion, and yes, tremendous love, all of which readers will happily return.

In “Who Look at Me” from 1969, Jordan wrote:

“I am

impossible to explain

remote from old and new interpretations

and yet

not exactly”

Two hundred pages later in “These Poems” (1977), she echoes the earlier poem:

“I am a stranger

learning to worship the strangers

around me

whoever you are

whoever I may become.”

We are still rightly fascinated by this icon, still trying to understand what Jordan has to impart. We are all impossible to explain, and all in the state of becoming. I can imagine no more an essential read than this book, this poet, these words, as we try to learn to worship the strangers around us and within us.

POETRY

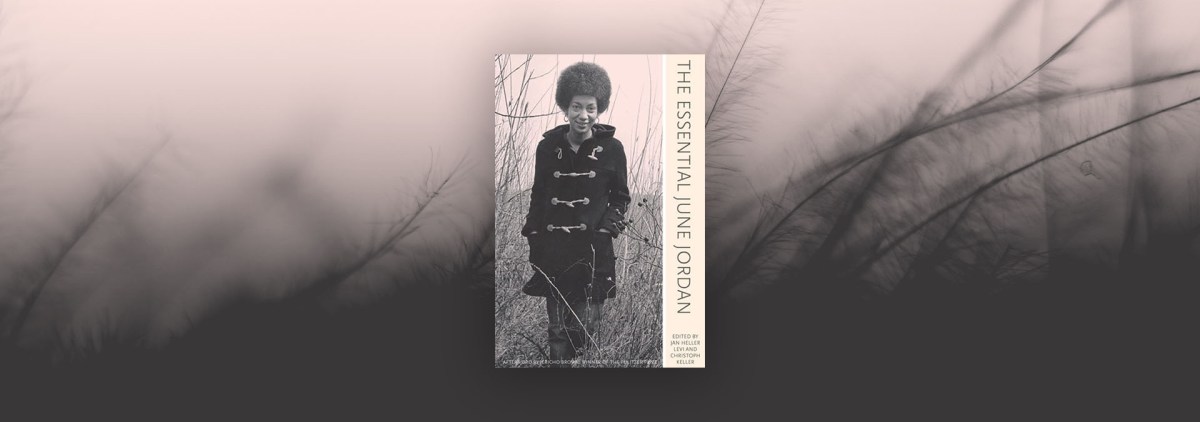

The Essential June Jordan

by June Jordan

Edited by Jan Heller Levi and Christoph Keller

Copper Canyon Press

Published May 4, 2021

[ad_2]

Source link