[ad_1]

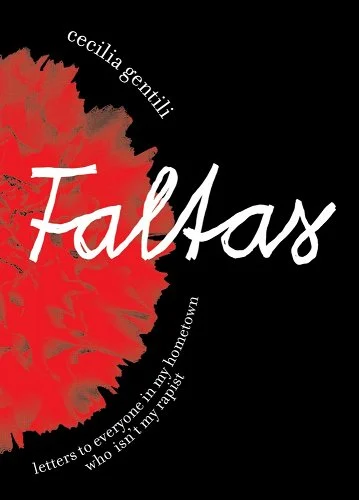

Before coming to America in search of a safer life as a transgender woman of color, renowned activist, performer, and now writer, Cecilia Gentili grew up in the small city of Galvez, Argentina, as the daughter of an Italian father and Argentinian mother. Faltas: Letters to Everyone in My Hometown Who Isn’t My Rapist, is Gentili’s first book: a raw, incandescent memoir outlined in eight letters all written to significant figures—for better and for worse—in her early life. The book is the second ground-breaking offering from LittlePuss Press, a new feminist press based in New York City run by two trans women.

While never directly addressed, the rapist in the memoir’s subtitle stalks specter-like through Gentili’s stories and memories, always there in the background. He is the father of Rosanna, a childhood acquaintance and the recipient of the memoir’s first letter: “Your father raped me. It started at age 6 and continued for years. He sexually abused me for the rest of my childhood and adolescence.” With a powerful and necessary frankness, Gentili describes instances of the abuse she endured, and the circumstances that made it possible, including the emotional and sometimes physical absence of her parents.

As a child, longing for the freedom of self-expression as the girl she knew herself to be, Gentili heartbreakingly acknowledges that her abuser used this knowledge against her: “I was a girl. He understood my femininity as normal…I remember the first time he laid eyes on me: I saw it, I saw he would give me that thing everyone else was denying me. He saw me as I was, and I didn’t have to explain how I felt inside because for him it was visible.” She goes on to define the cruel and painful paradox of the situation she was in: “He saw I was Cecilia. He saved my life and ruined it forever.”

Faltas is full of this kind of stunning descriptive language that cuts to the bone. It’s been argued that works of trauma shouldn’t be spoken of as works of art, but it’s impossible to deny that Gentili is a remarkable artist capturing the experience of brutality in the most unsparing of words. In one particularly evocative passage, Gentili relates to Rosanna the feeling of being pursued by her predatory father, offering the metaphor of a cheetah hunting a young gazelle: “Imagine that young gazelle, as if hypnotized, skips over to the cheetah and allows it to devour her, happy about it, as if the feeling of the fangs ripping into her tender flesh was a painful enjoyment, as if it illuminated her even as it killed her. And imagine nobody around makes a single move. Just as if it was not happening. That is exactly how I felt all those years while your father used my body. I let him—as I was letting everyone else—dictate my life and my sadness.”

Each letter Gentili writes is a reckoning with the past, a taking stock of the occasionally good and mostly bad in her relationships. She writes to her father’s mistress, gloating at her ultimate defeat; she writes to an older friend, who upon learning of the young Gentili’s ongoing abuse suggested she turn the situation into an opportunity to make money for the two of them; and she writes to her childhood tormentor, in undoubtedly the bitterest letter of the collection: “I realized you were just the first one, the one who was boldest with your hate, but that hate was everywhere, even if not always as dauntless as yours. It was subtle and sneaky at times; it even came indirectly through my mother and everyone else I cared about, whose lives were made just a bit more unbearable because I was in them…I still fear your judgment, and your sharp verdicts on my actions and life still haunt me.”

Happier memories are reserved for Gentili’s oldest friend, and for her beloved grandmother, who figures largely in the letters as her one constant, unconditional source of love and support, a counterbalance in the book to the shadowy presence of the author’s rapist. The most emotionally difficult letter is to Gentili’s mother for whom she has deeply complicated feelings. She tries to understand her mother’s shame, her motivations for her actions, and her need to hide the truth of her daughter’s reality, recognizing the overwhelming importance to her mother of the good opinion of others. Gentili’s effort to understand becomes even more unimaginable in light of the fact that her mother knew about the abuse her daughter endured and did nothing to stop it.Faltas is not a redemptive book or a story of victoriously emerging from a traumatic past, but that’s not its aim. It is a bitter book, written with crystal clear vision, by a woman determined to tell the truth and resolve unfinished business with people, some now dead, from the early years of her life. Is it difficult to read? Very much so, especially for those who have had similar experiences. What Faltas makes abundantly clear, though, is the incredible power—so often exploited—that we can yield over the lives and freedoms of others, particularly our children and youth, to devastating effect.

Nonfiction

Faltas: Letters to Everyone in My Hometown Who Isn’t My Rapist

By Cecilia Gentili

LittlePuss Press

Published October 4, 2022

[ad_2]

Source link