[ad_1]

Is the world of our everyday reality the only world we live in, and the realest one we can apprehend? For McPhail, the protagonist of Jonathan Geltner’s novel Absolute Music, the world of fantasy—“the other world that has no name or too many names,” a “world behind the world”—is not only real but all around us, exerting a power that can erupt into workaday reality both without warning, and with apocalyptic consequences.

The boundaries between these two worlds begin to break down for McPhail after a chance encounter with a pair of locust trees unearths a childhood memory of the sudden death of his first love Hannah. The dislodging of this memory, for McPhail so wrapped up in his belief in “the other world that lay all around, the invisible, fantastical world where everything that was important—everything that was real—happened, or could happen,” inaugurates a year of “remarkable coincidence and failure” that sends him on a journey into fantasy. This voyage is somewhere between the quest of a knight-errant through his own past memories and a particularly self-destructive midlife crisis. Along the way, McPhail loses his easy teaching job, cheats on his pregnant wife (whom he is intimidated by professionally) with a former student, and struggles to write his second novel before giving up on his aspirations as a writer entirely.

In McPhail, Geltner masterfully distinguishes between a true and childlike approach to fantasy, oriented towards a wonder that reveals (per the philosopher Josef Pieper) the transcendent foundations which underpin reality, versus a vain and childish vision of fantasy that collapses the transcendent into the self. Though McPhail, like Walker Percy’s Binx Bolling, seeks to find the deeper world behind quotidian life, this search for something beyond himself runs counter to his own intense self-absorption.

At the beginning of the novel, rather than visit old friends in Chicago, McPhail chooses to stay at home purportedly to work on his novel, leaving his wife, infant son, and infirm mother-in-law to make the journey alone. Rather than write, however, McPhail tries to disinter his childhood memories of Hannah by watching The Never-Ending Story and The Princess Bride. His overconfidence in his own academic abilities leads him to break with his school’s curriculum and go on long tangents while teaching, which only make sense to him. These pedagogical strategies inevitably get him fired. He fantasizes about moving his family away from their Detroit suburb to locations as disparate as Cincinnati and Japan, falling into the distinctly modern trap described by the philosopher-farmer Wendell Berry of seeking a phantasmal better life somewhere other than the place where one is. McPhail spurns the other fathers in his church’s community even while he—in a pivotal scene of the novel—fantasizes about having sex with one of their wives. Each of these choices, each of these falls, leads McPhail closer to the apocalypse of his own life, a destruction paralleled by the dissolution of the natural world he sees all around him.

McPhail is not ignorant of this connection between the deteriorating universe and his own failing moral character. At the halfway point of the novel, at the funeral of a beloved aunt which serves as a catalyst for his brief affair, McPhail observes that in the Jewish tradition “God fashions Adam from the dust (aphar) of the ground (ha-adamah). But that earthiness that is the stuff of life, aphar, comes from the same root that gives the word epher, the ashes that in the biblical mind are sign of mourning, disgust, humiliation, and shame, as when a penitent man or indeed a whole city covers itself in sackcloth and ashes.” In this paradox, that man is somehow both divinely sculpted dirt and shameful ashes, that the earth brings forth both good soil and “the muck and mire of space and time,” McPhail sees the relationship between fantasy and reality incarnated.

It is this constellation of connections—fantasy and reality, salvation and destruction, dirt and ashes, Adam and adamah, humus and human beings—that drives McPhail to seek reconciliation and forgiveness. McPhail realizes that if all things exist in relationality, to admit his faults “would be no more and no less than the admission that we all composed one flowing pattern, we all existed in relation or not at all, and my part of the pattern—or the part that I am—had gone askew, erred from its appointed way.” In his desperate spiral of concupiscent despair, he throws himself upon transcendent, divine mercy to free him and finds “no words, no thoughts, but an image […] of the mature white pine growing a hundred feet or higher over my neighbor’s yard, a perfect tree,” a contrast to his own “ruined landscape, mined and polluted.”

To grapple with the world of what McPhail calls fantasy, the world that is realer than reality, is to become multidimensional, to leave behind the one-dimensionality of a world that is as wide and broad as the infinitesimal dot of the self. Geltner’s novel sees clearly that to come face-to-face with our own brokenness, to grapple with the apocalypses that envelop our lives and the world in which we live, we must open ourselves up to a transcendent love that fills and enkindles the hearts of those who trust in it rather than themselves, a love that renews the face of the earth.

FICTION

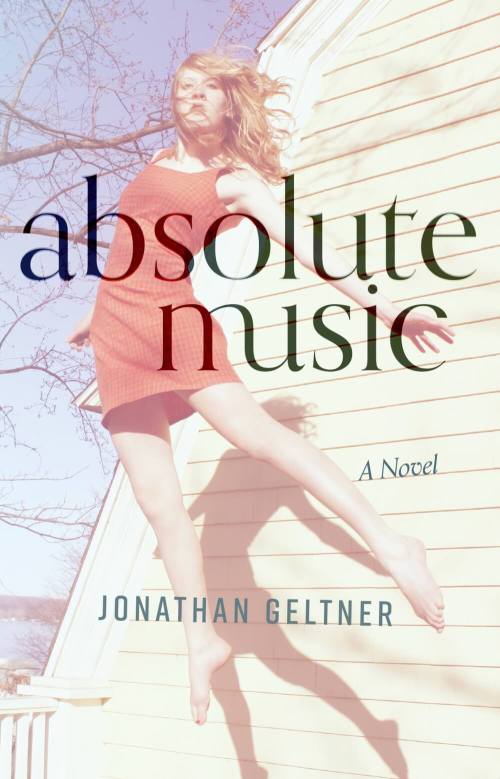

Absolute Music

by Jonathan Geltner

Slant Books

Published July 1st, 2022

[ad_2]

Source link