[ad_1]

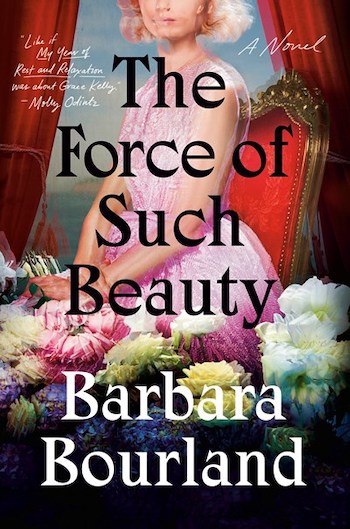

Forget Cinderella and The Little Mermaid. Barbara Bourland ups the fairytale game with her latest novel, The Force of Such Beauty. Bourland is a Baltimore resident and the author of three novels. Her first book, I’ll Eat When I’m Dead, won critical acclaim for its satirical exposé of the fashion industry; her second novel, Fake Like Me, focuses on a female artist as she discovers the mysterious truth about her creative idol. Bourland’s new novel is based on research of imprisoned historical princesses: its plot follows a female retired Olympian who is imprisoned in a fantastical kingdom. With humor and compassion, she uses the fairytale plotline to reflect how women are imprisoned within patriarchal societies. The setting of Force is fantastical, but the feminist undercurrents and the spirited female protagonist, Caroline, shine as brightly as the jewels that chain Caroline to her prince’s castle. While Bourland was abroad in South Africa—Caroline’s hometown in Force—she and I conducted our interview via email. Sharp, witty, and intellectually intense, Bourland’s prose is a force to be reckoned with.

Liv Albright

Caroline and her fellow citizens live under government surveillance, reminiscent of Foucault’s panopticon. In your first novel, I’ll Eat When I’m Dead, this theme pops up as well, with women internalizing the male gaze and monitoring their bodies. How did your interest in this theme arise? Can we use fiction to neutralize surveillance of female bodies?

Barbara Bourland

It’s rare that I feel unaware of the reflective spiral of self-surveillance and social conditioning about my physical appearance. I would also say this is also true for most of my friends. I hope fiction will engage these themes to allow the reader to pick at the knotty internal loops of our own conditioning. Maybe seeing a familiar problem through a fictional consciousness will break the knot. Eventually, I do think it’s possible to change the things you have been trained to see or believe, or at least change your feelings around that training. The more I confront the ideas, biases, and beliefs that I have inherited or ingested from the dominant power structures of my life, the easier it has become to alter those beliefs, change my behavior, and change my sense of self.

Liv Albright

In The Force of Such Beauty, Caroline’s job is basically to look beautiful as she is a revenue source for the royal family. What do you think about women’s appearance being tied to jobs that have nothing to do with appearance? How is the objectification of Caroline problematic?

Barbara Bourland

Everything in the world is a problem: mining practices for minerals for the battery of my computer. I bet at least one item of your clothing was made by the world’s poorest women. Your local grocery store sells acres of hydrogenated corn oil that gives Iowa some of its political power. Everything is an interconnected ethical, personal, political, and economic problem. Nearly everything is an opportunity for profit. I’m not opposed to profiting from self-adornment; this is the state of the world we live in. What I’m curious about opposing through ridicule is marketing that aims to conflate the spiritual with the practical: calling a “detox” tea “self-care” or pushing images of different-sized women covered in soap as a “beauty revolution.” Revolutions burn down buildings. Soap on naked buns is deliberately telegraphing sexuality, cleanliness, and implied availability, and also, just selling soap.

Liv Albright

After a horrible sports injury, Caroline gets facial reconstruction surgery. In a society where the Kardashians are queens, plastic surgery has taken a front seat in pop culture. What are your views?

Barbara Bourland

My personal view is that you can and should have the freedom to do absolutely anything you want to your own body. However, it seems very painful and scary. I think you’d have to be in deep emotional pain to tolerate the physical side effects of post-surgical healing. Caroline’s experience is meant to provoke sympathy in the reader that internalized misogyny otherwise prevents us from extending to women who change their faces for reasons of “vanity,” like the Kardashians or Meg Ryan or Renee Zellweger.

Liv Albright

How do you think a woman’s right to her body has improved? What changes do you recommend?

Barbara Bourland

A woman’s right to her body has not improved, at least here in the United States. Until we move from a political system that replicates monarchy in the unit of family—as in, a tax structure that delivers benefits to the primary earner, and not to the caretaker or dependents—towards one that views every single person as an equal individual, with the right to be dependent on the state, the right to healthcare, clean water, clean air, education, healthy food, and the right to choose, we will not have a society that respects a woman’s right to control the future of her own body, because that body will always be less meaningful, politically, than the family that it is attached to and reproduces on behalf of.

Liv Albright

Despite the fairytale theme, Force is infused with history. Caroline, a white woman from South Africa, lived during apartheid. She gives a speech at the Special Olympics that talks about people of different skin tones being violently separated during apartheid. Why did you choose to set the book in South Africa and to stress the apartheid theme?

Barbara Bourland

I’ve had the privilege to visit South Africa many times over the past 15 or so years. I’m always struck by its parallels to the United States in both the best and worst of ways: imperfect young democracies that built their wealth on enslavement and control of Black bodies. The shame of apartheid is profound, as is the shame of slavery in America. Shame can make us want to run and hide, to give up, to stop participating, to become cynical; disappointment in attempts at resolution can curdle into profound cynicism. Overpowered by those two things—shame and cynicism—Caroline becomes vulnerable to the lure of an autocrat. I think that is something many of us can relate to.

Liv Albright

In Force, the hook-shaped castle “Talon,” indeed hooks Caroline and reels her in like a fish. She’s caught and trapped. How do you use place and geography to convey the spirit of what’s to come?

Barbara Bourland

Place is a very important part of what allows you to just fall into a novel and stay there. I work until it feels right: I go to actual places and take notes about how the ground feels and the air smells, what the local ashtrays look like. I review archival photographs. I buy out-of-print biographies from used bookstores online for just the pictures in the middle. I scour Getty and Corbis for vintage editorial images. I read nonfiction for personal accounts. There is the “real place” I can observe, as myself, the person, but that place needs to become the world in which the characters live. It’s really a long, intense process.

Liv Albright

Frida Kahlo is mentioned several times in comparison to Caroline. Aside from being victims of horrible accidents, how do you think their stories relate?

Barbara Bourland

Frida Khalo spent her life in pain. She documented that pain and waited for the man she loved to be faithful and loving. She’s a highly gendered figure, as is Caroline. Finn gives her a biography in which he has underlined key phrases. It’s one of the ways in which Caroline sees romance in a moment when she is actually being controlled, dominated, or manipulated.

Liv Albright

Finn also fosters Caroline’s status as a kept trophy princess. With current discourse around toxic masculinity, do you think men can be feminists?

Barbara Bourland

Men can and should be feminists. We can all of us, every type of person that exists, work to dismantle the urges within ourselves not only to see other people as less, but to see ourselves as more.

Liv Albright

Fields and Waves, your next book, comes out in 2024. Will it also have a feminist angle?

Barbara Bourland

It’s different from the first three in that Fields and Waves is about what we hear, not what we see, per se. It follows a lonely female clairvoyant, who can actually hear other people’s thoughts. It involves empathy and connection. It is feminist, but it’s a secular story about God.

FICTION

by Barbara Bourland

Dutton

Published on July 19, 2022

[ad_2]

Source link