[ad_1]

Eric Nguyen’s debut novel Things We Lost to the Water is the story of a Vietnamese family that resettled in New Orleans after the Vietnam War. The novel is told from the perspectives of three characters: Hương, the mother, and her two sons, Tuấn and Ben. As Hương becomes gradually less hopeful about the possibility of reuniting with her husband, Công, Tuấn and Ben are forced to adapt to the absence of their father and their separation from Vietnam. What emerges is a novel which sensitively explores how these characters confront the feelings of alienation, grief, and trauma.

I spoke with Eric over Zoom about the diversity of New Orleans, the political critique of diasporic Vietnamese literature, the messiness of life, and the feelings of home and homelessness.

Sydney To

Numerous elements key the reader into the arrival of Hurricane Katrina. The effect is a double haunting throughout the novel: the war which is not over, and the natural disaster which has yet to come. What kind of stories have been told about Hurricane Katrina, and in what way is your novel a response to these stories?

Eric Nguyen

A lot of stories about Hurricane Katrina are about anger. My novel is not quite about that yet. Like other New Orleanians, the Vietnamese people in the city were angry after Hurricane Katrina. There was a lot of mismanagement. In particular, the plan of the city was to make New Orleans East into a dump and put all the trash and debris from the so-called main areas of New Orleans into New Orleans East. There was a lot of activism to prevent this from happening. My novel doesn’t really address that, because that happens after it ends.

My novel is more about the feeling of losing again. Vietnamese refugees have lost so much from the war. They come here, settle, and lose again. It’s that haunting—of never finding a home or not being able to settle that’s haunting my novel: that thought that you have to leave soon. It’s really ingrained in the refugee consciousness, I think, that you can get kicked out at any moment. That was the feeling of my characters and probably of Vietnamese in the New Orleans community, that something can be taken away from you so quickly without you having any say in it. I was trying to get at that universal refugee experience of how you can settle down but you can also lose everything that you built.

Sydney To

One typical feature of Vietnamese American literature is the double critique of both Vietnam and the US, communism and neoliberalism. This seems true of your novel as well. What do you understand the political potential of Vietnamese American literature to be?

Eric Nguyen

Vietnamese American literature, especially the newer literature, is not as closely connected to the War or communism or what happens in Vietnam after the Communist takeover. So I guess there’s that distance for people of my generation. I’m a millennial, who was born in the US. For us, there’s this distance. Vietnam is where our family comes from, but it’s not ours. We can visit many times, we can speak the language, we can know a lot about Vietnam as a country, but we never had a passport from Vietnam, for example. In that case, we are free to point out what is wrong with communism, like their censorship, but also admit that some of their other ideas might be okay. With COVID, for example, they were strong and quick to react. There were so few deaths there. I feel like this would get me into trouble with a lot of elders in the community—to say that something over there went well, to say that things are not so black-and-white.

Sydney To

An interesting character to discuss in relation to what you’re saying is Công, who was a professor of French literature in Vietnam before the Communist takeover. Notably, he lectures on “bourgeois writers.” This gets him in trouble with the Communist government, and it also influences the direction his son Ben takes later in life. What made you choose this career for him?

Eric Nguyen

I wanted to show the influence of French colonialism, and how the oppressed can find a way to survive and thrive and find meaning despite it all. How, for example, a Vietnamese person can take something from the colonizer and get something out of it, to make it something of meaning to him, a brown person who those white French writers never imagined reading their work. Công’s narrative is parallel with Ben’s, who doesn’t exactly embrace communism, but he falls in love with a communist and falls into a gang of so-called communists. [Those] ironies of history are what I was trying to get at. I’m interested in how history haunts us, but we can take that haunting and make it our own. One can’t change history, but one learns to live with it.

Sydney To

One of the ways in which younger Vietnamese Americans first encounter this haunting is through literature. I’m curious about your first experience with Vietnamese American literature. And how has your position as editor-in-chief of diaCRITICS influenced the kind of novel you wanted to write?

Eric Nguyen

My first experience with Vietnamese American literature was from an Asian American studies class during sophomore year of college. At that time, the only Asian writer I knew was Amy Tan. But the professor assigned the first chapter of Lan Cao’s Monkey Bridge. I read the chapter and found the rest of the book eventually, and it was really eye-opening. I lived a life that was sheltered from my parents’ experience of the Vietnam War. I felt like I found a piece of my history there, something which my parents had hidden from me to protect me.

From there, I only had more questions. Other books I read were The Gangster We Were All Looking For by lê thị diễm thúy and Aimee Phan’s We Should Never Meet. Those books gave me really different perspectives on the Vietnamese American experience. Aimee’s book is about Operation Babylift and these adoption stories. lê’s book is about this poor refugee family in San Diego, and how their traumas affected their present life. Before, it was more like: there was a war, and then we left the country. But that book showed me the emotional resonance of what war and being forced to leave the country can do to you.

As an editor at diaCRITICS, I learned more about the kinds of stories out there that Vietnamese diasporic people can write. I guess that gave me permission to write a novel set in the South. There aren’t a lot of novels about Asians in the South though there are many Asians who call the South home. So that’s something that needs to be explored. Reading those books by Vietnamese diasporic writers, and editing and learning more about Vietnamese writers working now gave me the permission, or the freedom, to take my story wherever it needs to go, and not have it limited by what mainstream American literary culture would say about what the Vietnamese American experience is.

Sydney To

This leads me to the multilingual aspects of the novel. Viet Thanh Nguyen says somewhere, “Writers from a minority, write as if you are the majority. Do not explain. Do not cater. Do not translate.” What was it like for you to write through multiple languages at once?

Eric Nguyen

While I’m writing, it’s really easy to slip into Vietnamese. I didn’t grow up in a completely bilingual household. My parents spoke Vietnamese to me, and I spoke Viet-English to them, but I also understood Vietnamese. It’s that cadence of changing words while you’re talking. It comes naturally to me, and I don’t even think about it. So once I’m on the page, it just happens. When you’re writing, you’re in character, and if Vietnamese is their first language, it’s just natural for them to grasp for a Vietnamese word but then just go back to the English, or vice versa.

Sydney To

The novel is very cosmopolitan. There’s the journey from Vietnam to New Orleans and back. You’re also very attentive to the local differences among cities in Vietnam, such as Đà Lạt, Vũng Tàu, and Mỹ Tho. Vietnamese refugees are living alongside Haitian refugees. One character goes to France because of his father. What kind of research went into writing a novel on such a global scale?

Eric Nguyen

A lot of the research was visiting the place. I lived in Louisiana for three years. I travelled to New Orleans to get attuned to the landscape and the differences between, for example, the French Quarter versus the Garden District versus New Orleans East. That’s just to say, everything is so different. You can just feel it. I tried to capture that on the page. I went to Paris one time, too. Being in the place helps you get attuned to it, especially if you’re open to it and push away any stereotypes you have of the place. It’s about feeling the temperature there, watching people walk around. That’s really important to do when you are setting a novel. But that’s not possible for everyone.

When I was a grad student, I would read about New Orleans, France, Vietnam. Reading helps too. And you can search anything on Google these days. If I couldn’t visit New Orleans, I would read The Times-Picayune. They would talk about local happenings, and you get a feel of the news and the people there. People say reading is transportive, that you can travel through reading, and I believe in that, as long as it is a book which comes from the heart. Not when someone just picks a place and sets their story there, just because it is exotic. But with someone who really loves a place, it will come through in the writing. And you can feel that and get that, hopefully, into your writing as well.

Sydney To

I’m intrigued by the temporal structure of your novel. Whereas most bildungsroman will divide a character’s life into two or three distinct phases, or else, let time pass by smoothly and gradually, your novel does something else. The novel takes place over the span of almost thirty years, and each chapter is given its own year, but these chapters and years are given to the reader only through specific moments. It makes me think of Walter Benjamin’s conception of history as not empty, homogenous time, but as he says, “a sequence of events like the beads of a rosary.” What aims did you have in structuring the novel this way?

Eric Nguyen

Each character had a different experience going through time. I split up the thirty years of narrative into different points of view, but also sifting in others. Each chapter is from a different point of view, but you also get updates from other characters. My aim was showing, from a higher level, the different experiences that different generations of Vietnamese Americans go through.

So you have Hương, who grew up in Vietnam and then flees to a new country. How is her experience of America and New Orleans different from her first son, Tuấn, who left when he was a child? He has some memories of Vietnam, but grew up immersed in New Orleans culture, Southern culture. How does this compare to his brother Ben, who hasn’t even stepped foot in Vietnam? He was born in a refugee camp. His experience as a mostly American-born person is different from people with other memories. I felt like through the thirty-year span, I can get one character’s focus for a little bit, and from there, go to someone else. This kaleidoscope or mosaic structure lets me give a bigger picture of what the Vietnamese experience might be like.

Sydney To

I see. So it was necessary to break up time in this way because the character’s lives and memories already make them so separate from one another.

Eric Nguyen

Yes.

Sydney To

The moment of coming out is one of the most central tropes of LGBT narratives, and your novel approaches it in a surprising way. The character Ben never comes out to his mother or brother, although there are numerous moments when they almost find out. Rather, he comes out to Addy, his best friend at the time, but she abandons him and ends up dating his brother. As a queer narrative, the ending is not only non-redemptive but ruthless in its realism. Why does the novel conclude the way it does?

Eric Nguyen

You mention a ruthless realism. That whole process of coming out is always messy. It doesn’t always go the way you want it. In the coming-out narratives we usually tell, it seems like everything ends up okay. But as a gay person, you come out over and over again throughout your lifetime. Sometimes they work out fine, sometimes they don’t. The messiness of life is part of queer life. That type of narrative, of coming out to your parents, wouldn’t have added much to my character’s story because Ben is a very independent character, he will do what he wants to do. Coming out might be important to some queer people, but it doesn’t have to be that “thing” which they want. They might just want to leave their past behind, for example, and start over. Once you see Ben in France, he tries to live a life with a so-called anarchist, but that doesn’t work out either. Things don’t always go as you plan. Hương, for example, plans to leave Vietnam with her husband, but that doesn’t happen either. That’s a theme in the novel. Your plans are never going to work.

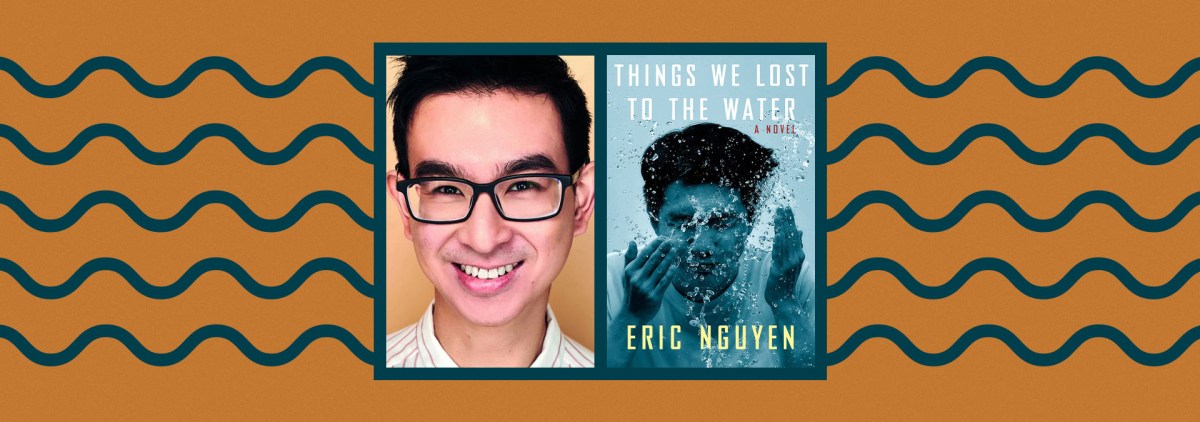

FICTION

Things We Lost To The Water

by Eric Nguyen

Knopf

Published May 4th, 2021

[ad_2]

Source link