[ad_1]

My friends and I have a running tally of how long we can go before someone we cross paths with mentions the Great Chicago Fire. It’s become something of a local twist to the “How often do you think of the Roman Empire” trend, where the topic happens to find its way into the strangest passing conversations and strolls through the city.

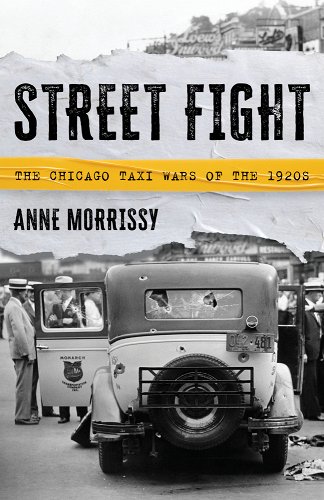

It makes sense why the most destructive or opulent events, like the Great Chicago Fire or the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, take up much of our historical imagination, because they were pivotal moments of transformation for the city. In Street Fight: The Chicago Taxi Wars of the 1920s, Anne Morrissy explores the turbulent history of an often forgotten moment that would leave blood in the streets and shape the modern landscape of Chicago.

Street Fight is a remarkable work of narrative history that tells the story of the complex rivalry between John D. Hertz’s (yes, that Hertz) Yellow Cab Company and Morris Markin’s Checker Taxi Company, which violently fought for dominance in the city’s nascent taxi industry. Morrissy carefully assembles these disparate instances of violence—from kidnappings and shootouts in the streets with passengers in the back seat, to fire-bombings—in all their harrowing and terrifying detail while highlighting the ways this conflict was uniquely Chicagoan in its construction.

I talked with Anne about her research process, the history of corporate warfare in America, and the parallels in the tactics employed by the taxi businesses and our modern ridesharing companies today.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Michael Welch

I’m a little embarrassed to say that even as a lifelong Chicagoan who really enjoys learning about the city’s history, I didn’t know much at all about the Chicago Taxi Wars before your book. How did you first become interested in this topic?

Anne Morrissy

You’re not alone! As I was working on the book, very few people I mentioned the project to had heard of this aspect of Chicago history, but honestly, I don’t remember a time when I didn’t know about the Taxi Wars, thanks to a family rumor whispered in hushed tones. My great-grandfather, Charles W. (“Charlie”) Gray had risen from the position of cab driver to eventually become president of the Yellow Cab Company. Less than two years later, he died in a freak incident in Jackson Park, leaving behind a wife and six kids under the age of twelve. It was 1927, and the Taxi Wars had been in full effect for over a decade at that point. Was his death somehow related?

Because of this family rumor, I wanted to know more about these Taxi Wars that gripped the streets of Chicago in the 1920s, so I started researching. And researching. And researching. The stories I uncovered were more violent, shocking and cold-blooded than I would have ever imagined. Mass shootings, bombings, targeted murders, political corruption, jury and witness tampering, extortion… I couldn’t believe that nobody today knew anything about it. Somehow, our collective memory had failed. That’s how I knew I had to write this book.

Michael Welch

Street Fight often reads like a captivating crime drama, with the majority of the conflict playing out across moments of violence and in news articles and paid print advertisements in the papers. How did you go about compiling and organizing this story through the media of the time?

Anne Morrissy

Piecing together a 100-year-old “forgotten” Chicago story was extremely challenging, and it wouldn’t have been possible without the digitization of countless newspapers. In this case, journalism truly was the “first rough draft of history,” as the adage goes, and until now, it has been the only draft. My research assistant, Abby Foster, and I spent hundreds of hours keyword-searching digital newspaper databases (and then sometimes also scrolling through microfilm) for any mention of the key players and events of the Taxi Wars. All told, I collected well over one thousand newspaper clippings from the roughly fifteen year period the book covers.

On top of that, I often just got lucky in my search for details about specific events. In sleuthing for more information about the Hotel La Salle’s in-house taxi department, for example, I discovered a trove of original business documents in the “Ernest J. Stevens” papers at the Abakanowicz Research Center at the Chicago History Museum. In searching for more information about the murder of Yellow Cab driver Thomas A. Skirven, Jr., I discovered a published memoir written by the son of one of his convicted murderers, in which the author writes extensively about the case against his father. In trying to disentangle the complicated allegiances of the key players involved in the Checker Taxi civil war (which pitted gangster-affiliated union drivers against a “secret cabal” within the company trying to gain control), I relied on court cases in district, state and federal courts, the summaries of which turned up in digital database searches.

The most incredible research tool that found its way to me during this project was a large scrapbook containing every issue of the Taxigram published between 1919 and 1921. The Taxigram was the Yellow Cab employee newsletter, and someone in 1921 had bound these issues and presented them to my great-grandfather in an embossed cover. It had somehow remained in the family all these years and was sitting in a secretary desk in my aunt’s house, against all odds. These newsletters provided invaluable information about the on- and off-duty lives of Yellow Cab drivers and the systems and processes developed by the taxi industry during this era.

Michael Welch

In many ways this feels like a uniquely Chicago conflict, as it occurs at the center of the overlapping issues of the rise of unions and their violent suppression, government corruption, racial tensions, and organized crime of the Prohibition era. Can you talk more about the ways these various conflicts shaped the wars?

Anne Morrissy

You’re absolutely right — while other cities experienced some taxi-related street violence during this era as well, there were many external factors in Chicago that made our Taxi Wars so hyperbolic and long-lasting. When I first started writing this story, I assumed that the union was genuinely looking out for the welfare of its members. But what I learned is that, during this period, organized crime was deeply enmeshed with the union leadership and would often use paid muscle to bully, assault, overpower and intimidate the union drivers into doing its bidding. This was a big source of the tensions and battles surrounding the civil war at Checker Taxi, which led to some of the most violent incidents in the book.

Then there were the ongoing accusations of political corruption—part of Yellow Cab’s meteoric success can be credited to Walden Shaw and John Hertz and their ability to navigate the complex local politics of the 1910s and 1920s, emerging as civic leaders in the public transportation sphere under both Mayors Dever and William Hale “Big Bill” Thompson. This led to frequent accusations that they exerted undue influence over the city and used their power to benefit their own company at the expense of their competitors, though I am not sure that these accusations were always entirely fair.

The racial tensions in the city at the time were impossible to avoid (I write about the 1919 “Race Riot” and the concurrent public transportation strike in the book), but I was surprised to learn that the two biggest taxi companies, Yellow Cab and Checker Taxi, embraced racially egalitarian policies that were years ahead of their time. The leaders of both companies were Jewish immigrants to America, and possibly because of this, they actively worked to promote fair hiring practices in their companies. Checker Taxi is credited as the first cab company to hire Black drivers, for example. As early as 1919, Yellow Cab was reminding its drivers in the Taxigram, “Any driver found guilty of incivility on account of a man’s color or race will be in serious trouble; this applies particularly to 27th and State, and 35th and State,” or Yellow Cab’s taxi stands in the city’s Black Belt.

Michael Welch

You write toward the end of the book that “Chicago’s taxi industry was a business where you could lose everything, including your life.” With America having a long history of corporate warfare, what made the Chicago taxi industry in this era particularly stand out?

Anne Morrissy

What I found so compelling about this story was how dangerously it overlapped with the daily lives of average Chicagoans. My perception of most corporate warfare is that it happens behind closed doors, in board rooms, or at least in a setting far removed from the average consumer. But the battles of the Taxi Wars in Chicago were often happening in full view of the public, posing a significant threat to cab passengers and even people just passing by on the street.

There are several harrowing stories in the book of passengers cowering in the backseat as a taxi driver pulls up alongside their cab and starts shooting at their driver. There are also stories of passersby getting injured and even killed when bombs explode in taxi garages and popular driver hangouts. Over a decade and a half, the body count of the Taxi Wars was truly stunning, and some of the victims were just bystanders in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Michael Welch

Can you talk about the ways the taxi system shaped the way Chicago is constructed today?

Anne Morrissy

In terms of the city’s transportation landscape, it’s hard to overstate the influence John Hertz has had on the modern city of Chicago. He and Walden Shaw created one of the first—if not the first—comprehensive taxi corporations in the country, which included not just cab service, but also cab manufacturing, maintenance, dispatching and insurance services. They created the ambitious and successful template for what a modern cab company could be, and it was then mimicked around the world.

Next, in 1923, Hertz was eager to solve traffic congestion problems in the Loop to improve the taxi experience. Through Yellow Cab, he gifted the city its first stoplight system along Michigan Avenue between the river and 22nd Street. His hope was that people would see how effectively stoplights could improve traffic flow, and the city would then adopt the system in other areas. (I like to joke that every time you get stuck at a red light in Chicago, you can thank John Hertz.)

I didn’t have a chance to get into this in the book, but six years earlier, in 1917, Hertz had also begun working closely with the city to manufacture the first automobile buses and establish new bus routes. He vigorously lobbied for the city to maintain control of these, rather than allow private companies to own each route, which was how the streetcar system operated. It took several decades, but the CTA eventually heeded Hertz’s advice and took control of his City Motor Coach Company and all of its routes in 1952.

Of course, Hertz also famously pioneered the rental car industry, opening his first Hertz Drive-Your-Self stations in Chicago and Louisville, Kentucky in 1924. And in the 1930s, the company opened the first airport rental car counter at Chicago’s Midway Airport. So anyone who has ever been in a cab, bus or rental car in Chicago has benefited from Hertz’s efforts during the era of the Taxi Wars.

Michael Welch

While I was reading about this fight for supremacy and monopoly over the city, I couldn’t help but think about the modern ridesharing system. What parallels do you see between some of the tactics employed by the taxi companies in the 1920s and Uber and Lyft today?

Anne Morrissy

The tactics used in the Taxi Wars of the 1920s were particularly dangerous and violent, so I am grateful that the rise of rideshare companies has not been quite as dramatic! However, when ridesharing first started, what those companies were essentially offering was a new way to hail and pay for a cab. Yet they didn’t like the idea of adhering to the rules and regulations affecting taxis, so they recruited their own drivers (who provided their own cars) and claimed that the longstanding taxi rules didn’t apply to them. In fact, there was a similar fight going on during the Taxi Wars, with Checker Taxi and several smaller taxi companies refusing to adhere to some of the city’s newly established licensing requirements.

What you’ll learn from reading my book is that a lot of those requirements, rules and regulations still affecting the taxi industry in the 21st century were passed by the city council in the 1920s to protect the taxi-riding public in response to the Taxi Wars. Rules like city background checks on drivers, annual city inspections of vehicles, regulated rates that could not be changed at the driver’s or taxi company’s whim… these were all consumer safeguards put in place here in Chicago during the 1920s, many of which were then adopted by other cities around the country. Most people today—and I suspect even the rideshare companies themselves—don’t realize that a lot of blood was spilled along the way to establishing those rules. That was another big reason I felt compelled to write this book.

NONFICTION

Street Fight: The Chicago Taxi Wars of the 1920s

By Anne Morrissy

Lyons Press

Published March 5, 2024

[ad_2]

Source link