[ad_1]

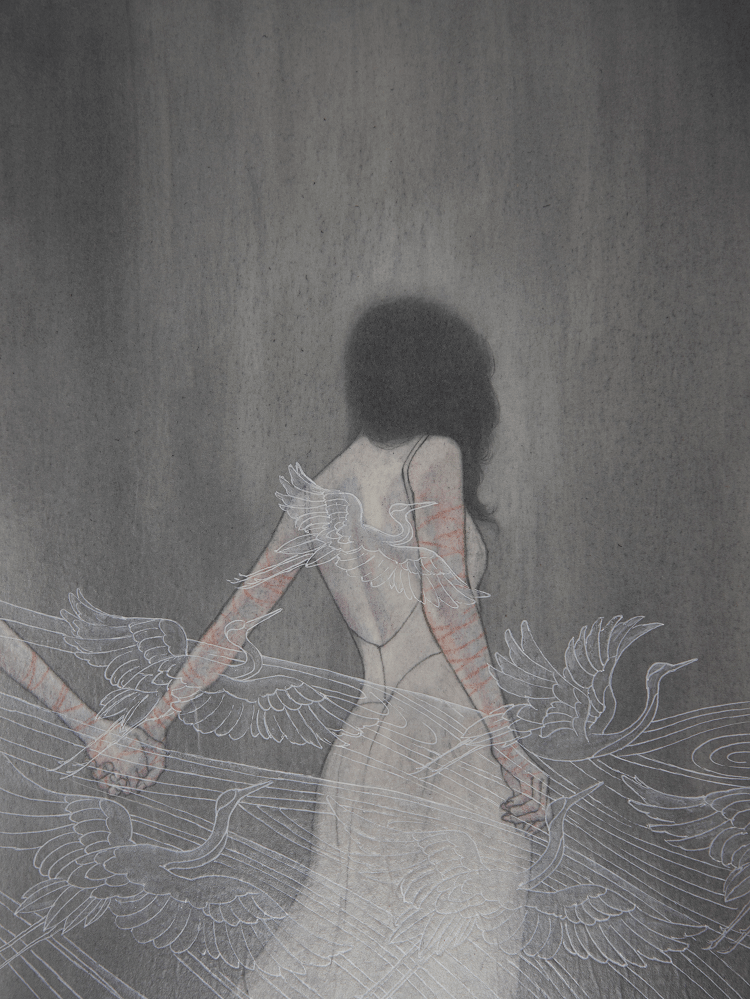

Nothing tears two women apart like the men who want and take indiscriminately. In this retelling of “The Crane Wife”, a makeup artist and her actress lover struggle to stay together as the glitz and glamour of old Hollywood transforms into a cruel and manipulative beast that threatens to pluck them apart.

Content warning: This story contains fictional depictions of domestic violence.

“Today,” she says, “we are women who are actually cranes.” Her hair is loose and her face is bare. Off to the side, her wedding dress lies strewn across an entire hotel room bed, train trickling down, a stream of white silk shot through with crimson ribbon. “Do you remember?” she asks.

You remember. You hated that story when you were younger: the molting feathers, the discovery, the betrayal, the abrupt, unsatisfactory conclusion.

“Hey,” she says. The engagement band on her delicate finger gleams in the light. “It’s only a story. And today we are cranes because I say we are beautiful, beautiful cranes.” She tips your chin and her kiss is a resolution, not a promise. You shouldn’t have agreed to see her before the nuptials, but she asked, and you can never say no.

“Okay,” you say. You unpack your bag, lay out the tools of your trade, the colors and powders and stains. While her face is still naked and true, you reach out, cup her cheek, whisper, “Marry me.” You will never tire of saying it.

Everything from the fading stars to the hotel Bible holds its breath. She beams. She breaks into helpless laughter. She gestures at the wedding gown and presses your hands to her tired face.

You nod and pull yourself together, stretch her arm out toward you, and begin to dream of wings.

Once upon a time, there lived a man who found a wounded crane upon his doorstep. Deep in the bird’s breast lay a fletched arrow. A slick spill of blood stained her feathers a furious shade of red, the exact shade of a poppy gone to rot. The man pressed his hands to the wound and, beneath the squelch and gore, he felt a heart that still fought, pounding back against his palm. He had no obligation to the crane, but its beauty, its tragic majesty, moved him. “I will care for you,” he told the crane. “I promise, I promise, I promise.”

It has always been the two of you, ever since you were both jam-handed and pulling the fat, flowered heads of roses off of the bushes in your front yard. You do everything together and never question it. In high school, when she stars as the lead in a few musicals, you attend every show. You fill sketchbooks and canvases with your waking dream: the same girl aging in real time, standing, singing, smiling, in repose; yours, kept pressed between the pages. When junior prom comes around, you get ready together in her bedroom, zipping up dresses, surrounded by tubes of lip gloss and a rainbow of eye tints. The night is perfect and she looks so lovely. She closes her eyes and tilts her head for the touch of a blending brush, and so you kiss her.

It is no surprise, then, that you follow her into the city for the auditions and part-time jobs, the two-bedroom shit apartment you share with one bed made up for show and the other rumpled from two bodies curled close. By day, you attend beauty school and ache with her absence. By night, you dream of the lives you could have together, all the scripts and wardrobe decisions, together, entangled. “Marry me,” you practice whispering as she sleeps. Anything feels possible with her body warm next to yours.

Neither of you feel the world shift the day she books a job, a shoot in the same city where you tear ticket stubs and buy your groceries and make love and exist. You do her makeup for her, at her insistence; for good luck, she says. She leaves in the morning and comes home at night and so you go on. Absolutely nothing changes until everything does.

The movie premieres. Her face is in subways tunnels and on billboards, lovely and large as the moon.

Suddenly everyone wants to stake their claim.

The night before her first televised interview, she sits in bed, breathing into a paper bag. She clings to you and you hold her together with your own two hands. “Come with me,” she insists. “Tomorrow. We’ll tell everyone that only you can do my makeup. It can’t be anyone else. Please.”

It’s how you end up backstage in a small dressing room, murmuring encouragement as you stain her eyelids purple and gold. Turning her face this way and that, you lift the apple of her cheeks with a blush soft as plum blossoms. You rouge her lips into a pink slick as a sliced peach. You hide away the little girl who used to scribble on sheet music and eat too many jam sandwiches and give her a mask to hide behind instead. When you watch her smiling and chatting nervously on the television monitor later, you know you are the only one who can peek behind this version of her. Only you have held her face between two hands and seen the truth of her, brilliant and terrified and beautiful. You think, I am going to marry that woman.

And then her costar walks out to thunderous applause. As he answers questions, he keeps touching her forearm, resting his hand on her thigh. Only you seem to be able to see the way her smile goes rigid. As they depart, he draws her close. She disappears into his embrace, cut from sight like a bird shot from the sky.

There is no question, then: The man takes the injured crane into his home and tends to it with great patience and care. The crane seems to understand his intent, and so allows the touch of his rough hands, the stink of wood smoke and musk that stings. She bears it as best she can. Eventually, she recovers.

There is no question, then: The man must release her. He has no use for a crane, no matter how beautiful. He takes her out of the woods. The sky stretches out. The crane flies far.

But that is not where this tale ends.

The very next evening, a woman appears at the man’s door, beautiful and majestic. She gives no indication that she is a changeling, once a crane. And what reason would the man have to believe in such magic? No version of the story will say.

In any case, it is always the same: The man falls in love.

(Does the woman?)

In any case, they marry.

“I don’t understand,” she says. Her manager has called her in for a discussion. They want photos and flirting and more, playing things up to build buzz for the film. The handsome lead and the beautiful ingénue: It is a story that writes itself.

She looks to you for an answer. You will not be the one to hold her back. You tell her, “I have an idea. Trust me.”

You get out your growing sprawl of cosmetics. For her first awards show, you send her out covered in shimmering camellias and barbed butterflies that spiral down her bare arms, fading into the faint lines of her blue, blue veins. You saturate those delicate petals and wings with all the venom in your heart. You line her eyes sharp as spears. You leave a giant golden flower, bulbous with poison, where her costar is most apt to smack wet kisses. If you cannot show that she is yours and you are hers, then you can at least make them all realize that their touches will be rebuffed, profane and unworthy.

He doesn’t lay a hand on her. (Not that night.)

From then on you give her everything in you: labyrinthine shapes like magic runes, drawn in neon for a fashion show; poetry that curls around the shells of her ear, creeping down her exposed neck, wrapping like a gauntlet round her elbow; a splash of cherry blossoms connected by branches that become swollen stitches, lines becoming giant centipedes, white and delicate as lace, curling protectively around her jaw, for a dinner out she cannot avoid.

You shield her from what you can, but her face is in every magazine and newspaper, and her costar is right there with her. You follow her dutifully and remind yourself that this was your dream. (Somewhere between the shifting planes of each transformation, you buy a ring, deep gold, diamonds and devotion.) But people can only reach out for so long and the barricades you build together stretch only so high. Their touches begin to land, and there is only flesh beneath the fantasies you sear into her skin.

The first time it happens, you are waiting to prep her for some industry event. She comes home and won’t look you in the eye. She is already crying and you don’t understand until she removes her coat and you see the ring of bruises around her biceps. “Don’t be mad.”

“Who did this?” you ask her—can’t look at it, start to reach out, think better of it.

“I told them I didn’t want to do it anymore.” She shakes her head. “They’re going to ruin everything if I tell. The things they said . . .”

(You think about the ring hidden in a shoebox under your side of the bed.)

That night you don’t bother color correcting the indigo and violet smudges that form stepping stones around her arm. Instead, you smear on black body paint, thick and angry as an oil spill. From shoulder to fingertip, you turn her skin unrelenting and then pull from it shining galaxies, deep and dark as lost strength, swirling with all the sadness in your veins. You waft a nebula against the expanse of her forearm. You fill the spaces beneath her puffy eyes with glittering stars fallen.

When you kiss her, it is not a proposal, but it is a promise and a lie all the same.

“It’s okay,” you tell her. “We’re going to be okay.”

Here is the crux of the tale. The man is poor, so his new lady love, this mysterious woman, this maybe crane, offers up her one skill: She can weave the finest silk, but only in secret. She makes her new husband promise never to set eyes on her work, not even a peek. What else can he do? The man agrees. He buys her a loom. He keeps the doors tightly shut. Soon, the house fills with the endless creak of the warp and weft.

When the woman emerges, hours later, she carries with her yards of gorgeous silk, light as air, soft as cream, every inch dyed a bright vermilion. Taken to market, each yard sells for the highest prices. Soon the couple are able to live comfortably.

(Do not ask: How did the man earn his living before this miracle?)

After so many months of weaving day and night, the woman’s pallor sinks to gray. She can never seem to keep warm. She does not eat. Still, she churns out the silk to take to market. Whenever she is not working, she sleeps and the house falls silent.

(Do not ask: Does the man ever offer to help?)

The man wears red silk slippers. He furnishes the house with fine food and rare jewels. When buyers praise his wife’s work, he tells them all how he is desperately, deeply, achingly in love.

(Do not ask, ever: Would the crane wife be able to say the same?)

“Today,” she says, “make me something far away.” You brush her skin gray and wash her out, turning her flesh to television static. You push her behind all the noise and let her stay there, somewhere numb with pins and needles. Above it all, you overdraw her mouth and paint it a magenta so garish that no one can see the split lip she sports beneath. She still draws it tight in a perfect smile.

“Today,” she says, “remind me how it used to feel.” You grow fat-headed roses around the sunken curve of her right eye and layer on foundation so heavy that the page of music you shade into her eyelid has the exact texture of aged parchment. The shiner beneath only adds a depth that no one else can seem to replicate.

“Today,” she says in a rasp, but can say no more because of the ring of bruises like sapphires around her neck.

You reach beneath the bed for the shoebox one night because you cannot stand it. You know it is the wrong time. “Marry me,” you say, fumbling the ring. You have only one free hand. The other holds a bag of frozen peas to her swollen rib cage. “We’ll go away from here. We’ll start over.”

There is a moment when her eyes slide away to the magazines and bundled script pages, the view from the new apartment, the billboards and city beyond. It is just a moment. Her gaze returns to you, red and puffy as a poppy gone to rot.

“Marry me,” you ask again. When you try to smooth away her tears, you only manage to rub the salt into her skin. It is then that she shows you the unsigned contract that came with the diamond and platinum monstrosity that has taken your place on her ring finger. Through your tears, she is someone you cannot recognize, bare-faced and broken.

The man grows curious or he forgets or he ignores the consequences or he simply doesn’t care. The point is: Eventually he disregards his wife’s one request. He looks.

This is what he sees: The woman he claims to love, wasting away, yet, still, she weaves. Rummaging beneath the fabric that conceals her hunched flesh, she seems to pull. Extracting part of herself, she jams it into the loom. The blood drips from her fingers. (Is it her feathered body plucked raw? Is it her thin human skin sliced open?)

Inch by inch, red silk emerges. The finest in the land.

(The result is the same: She stitches herself into the silk. She tells her husband to sell it to make him happy.)

The woman turns to look. She knew he would be there someday. Perhaps her human face falls away and the crane appears, blood trickling from its breast, a wound reopened. Perhaps her human face remains—attached to her human body, her human destruction—for no reason at all except so that she can finally say, “My love, where are your promises now?”

“Today,” she says, “we are women who are actually cranes.”

The crane wife is supposed to fly away in the end, never to return.

“Today we are cranes because I say we are beautiful, beautiful cranes.”

Did you stop to wonder how the crane came to the man’s doorstep in the first place?

“Marry me,” you beg.

Did he shoot her out of the sky himself?

You walk her down the aisle in matching white dresses like when you were children. The wings down your bare arms are identical to hers, pearlescent white tipped with coal black. (It is just a story, but you can feel the spill of blood down your chest, the damp forest floor at your feet. The fletched arrow came from nowhere and now you are looking up at the sky.)

Her costar stands at the altar. Her manager peeks out from the front row. Frankly, you want to rip your own skin to shreds, but this is the story she has chosen to weave with her own blood and bone and tears.

(Cranes mate for life.)

You walk down the aisle together, like it was always meant to be. (You support her weight as she works off her veil, one-handed.) There are freesias everywhere. (You keep her balance as she tugs at her dress, leaving it behind, molted feathers.) You feel the heat of tears hit you. (She walks with her beaten body on display, blues and greens that swirl into yellows, her ribs and thighs and back.) Her costar pulls nervously at the knot of his tie. (She scrubs her arm across all the makeup you’ve carefully applied.) They stand next to one another, face-to-face.

The camera flashes go off like an enchantment.

(Tomorrow, the photos will drop, the record you’ve taken of the damage over time, feathers plucked from her own raw and battered flank, woven into the story she never truly owned.)

The entire congregation hushes.

(Half-naked, winged, bleeding, she drops to one knee. “Marry me,” she says. And you say, “Yes.”)

You fly away into the sunset, like a movie, like a fairy tale, like another pretty story of love and sacrifice and freedom. You weave your feathers into the loom, the warp and weft and pattern, your blood adding punctuation to each lie, crossing out every single truth. You look over your shoulder for the betrayal. You tell yourself, “I will care for her and she will care for me, and we will live happily ever after.” The creak of the loom echoes, “I promise, I promise, I promise.” These days, when you pull your skin apart in the name of love, you do not even feel the pain. You weave your story. You set it free.

“Blood in the Thread” copyright © 2021 by Cheri Kamei

Art copyright © 2021 by Reiko Murakami

[ad_2]

Source link