[ad_1]

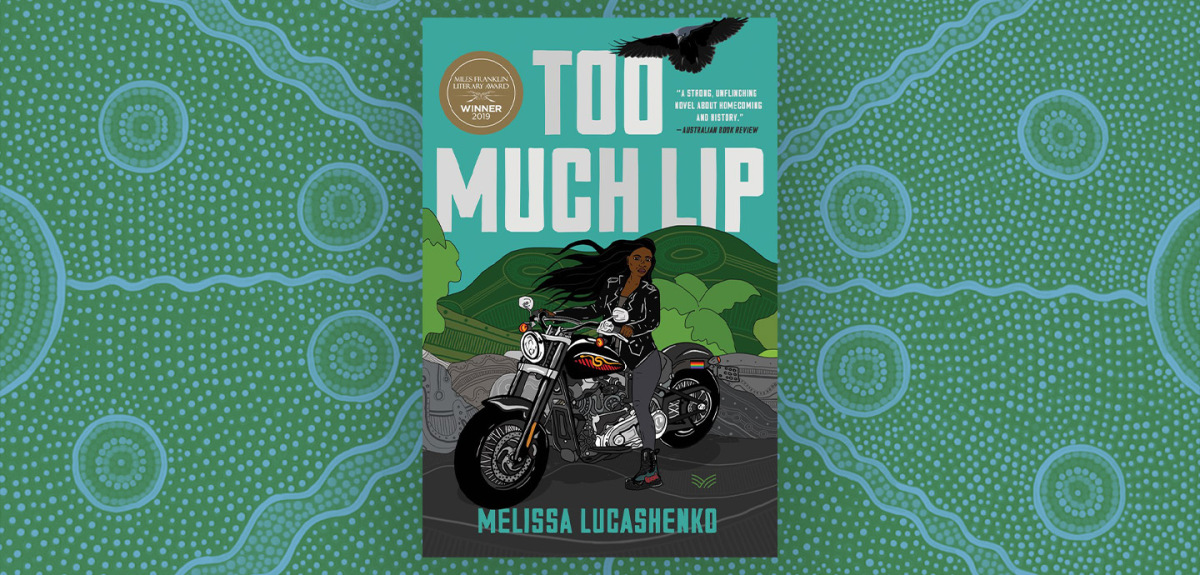

Melissa Lucashenko’s novel Too Much Lip tells the story of stolen land and stolen children. Though these crimes are assigned to the past, their violent legacies – poverty, addiction, abuse, discrimination – still plague the Bundjalung Nation, an Aboriginal community whose ancestral homelands lie along the northern coast of New South Wales, Australia.

But this is not a story of suffering. This is a story of fighting back.

We meet Kerry Salter, a Bundjalung woman, as she sits on her Harley, idling at an empty intersection. Although she is fleeing the heartbreak of a broken relationship with her newly-imprisoned girlfriend back in Brisbane and dodging several warrants for her own arrest, she is nevertheless reluctant to proceed to her destination: her dilapidated family home just outside of the small town of Durrongo.

It’s a complicated homecoming. Not only is her grandfather dying of cancer, relationships within her family are fraught. Her mother Pretty Mary thinks of Kerry as the “Great Abandoner” for her move away from home and her infrequent visits; her brother Ken is an angry, abusive alcoholic; her nephew Donny is troubled and withdrawn; and her only sister Donna has been missing since Kerry was fourteen. While Kerry is close to her other brother, Black Superman, he too left Durrongo for Sydney, leaving Kerry without an ally.

During her visit, Kerry retreats to Ava’s Island, a beautiful, wild place named for her great-grandmother who fled there to escape white violence. The island holds the graves of several of her beloved ancestors, as well as her happiest childhood memories. It’s Kerry’s “native church…built right here of rock and sand and feather and bark and moss.” But she is horrified to discover that the land is being rezoned and sold to build a prison.

The Salter family, however fractious, can unite around one thing: saving their ancestral land. As they work toward their common goal, Kerry and her family struggle with challenges both logistical and spiritual: money and racism, bureaucracy and grief, the corruption of local officials and trauma. Their fight to preserve the past reveals scars, surprises, and secrets that will determine the path of the family’s future.

Lucashenko’s writing glides steadily forward even as it expands outward beyond Kerry’s point of view, moving smoothly from one character’s thoughts to another’s. As we come to know each of their motivations and limitations, we see the prismatic effects of colonialism’s violence and racism, damage cascading down through generations.

Lucashenko deftly voices these characters’ pain and rage, but her humor also crackles across the pages. The writing is consistently funny, but rather than serving to soften or balance, the humor instead lances and sharpens and reveals.

When a eulogy turns into an impassioned call to arms to defend Bundjalung land from the proposed prison, Lucashenko describes the congregation’s rousing approval:

“The blackfellas in the church cheered loud and long. A show, a bit of excitement for once in the sleepy country town that was Patterson! This was a lot more like it! Pretty Mary cried out in wild agreement and waved her sodden hanky enthusiastically in the air, unfortunately seeming to signal surrender, but everyone knew what she meant.”

And in an otherwise tense confrontation with the police at a family birthday party, the Salters have some fun by reframing the usual admonishments about crime in the Aboriginal community to fit the theft of their land by whites:

“‘Darnt. I feel sorry for whitefellas, going around thieving all the time. They need help. Shame nobody ever tries to get em back to their culture.’ Black Superman shook his head in deep, patronizing sorrow.

‘I blame the parents,’ interjected Zippo from the back of the group.

‘Yeah, bruz, true, eh,’ Ken said to Black Superman. He chastised the cops. ‘You mob wanna take these whitefellas round here up to the city. Show em some of their sacred sites. Shopping malls and factories and shit.’”

Bundjalung culture, both sacred and ordinary, courses through the veins of Too Much Lip. The characters’ Australian English is studded with words in the Bundjalung language. Culturally significant animals – the crow (waark), the brown snake (mundoolun), and the bull shark (wardham) – are seamlessly woven into the story, each to stunning effect. The characters’ love for their ancestors, the Old People, and the land they lived on makes it possible for Kerry and her family to draw resilience from the past as they face each other, and together, the future.

Vibrating with energy, both heartrending and hilarious, Too Much Lip offers a compelling multi-dimensional portrait of human strength in the face of human failure.

[ad_2]

Source link