[ad_1]

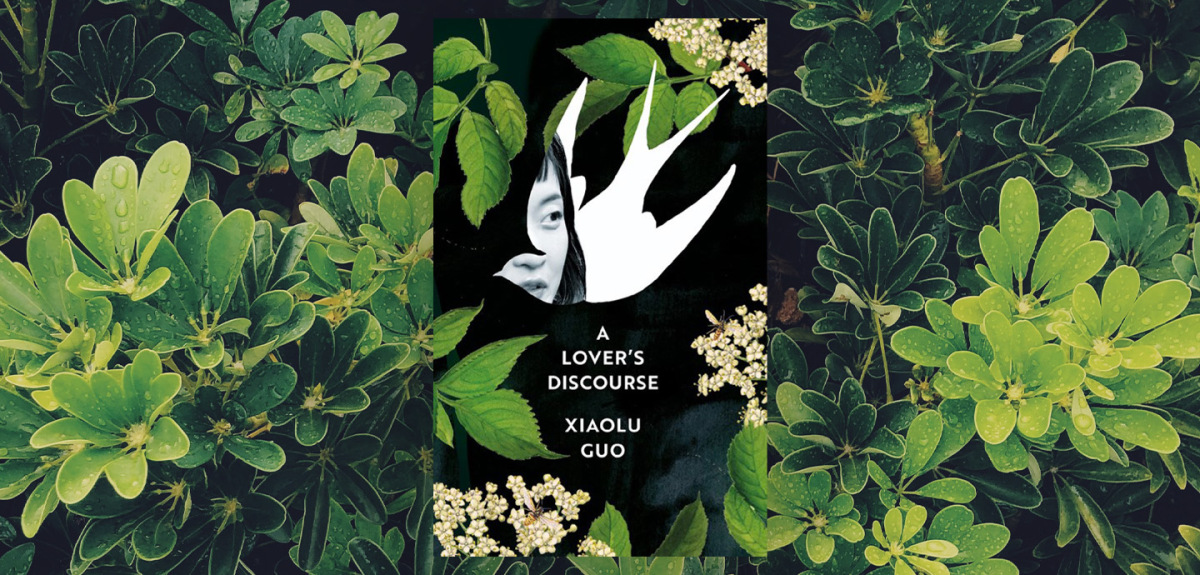

Can people in love ever really understand one another? That is the question at the center of Xiaolu Guo’s latest novel, A Lover’s Discourse. The titular lover is an unnamed woman from southern China, newly arrived in London to complete a Ph.D. program. She develops a relationship with a German-Austrialian landscape architect, also nameless and addressed as “you” throughout. Their life quickly becomes romantic. They buy a small, dilapidated houseboat and name it Misty. When they have a child, they leave the boat and eventually buy a plot of land in Germany on an old mining shaft turned landfill. The man sees potential and they build a secluded, peaceful home there before returning to London to live in an old lockkeeper’s hut by the canal.

These snapshots could be quaint in another writer’s hands, but Guo places them in the backseat to the confusion and missed connections within the relationship. They often question each others’ work. He suggests that she is dehumanizing Chinese workers in her dissertation by analyzing them in terms of mechanical reproduction. When he takes her to a garden he particularly likes, she scoffs, “I mean, isn’t this some postmodern superfluous industrial landscape? I’d rather have the natural design of a real landscape, not designed by an expert.”

Their relationship is set against the backdrop of Brexit, which highlights the characters’ differences. Neither character is a native Brit, but she is more of an outsider due to her race and her student visa. Reports come of a mass exodus of Europeans from the country. But for the protagonist, there is no home to which she can return. Both her parents died before she left China. When she does return for schoolwork, she feels like an outsider.

His Europeanness and, as she learns when she meets his family, upper-middle-class upbringing provide him with a natural security that she lacks. While they are living on the boat, she tells him that she feels like a part of the rootless generation, a descriptor for millennials who grew up in cities. “I don’t feel I’m rootless,” he says. She tells him she does. “And this kind of life has made me feel even more rootless.”

Guo, who came to England from China, is no stranger to autobiographical novels. She has written another one with the familiar-sounding title A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers about a Chinese woman in London who falls in love with an Englishman. She seems to isolate themes in her own life and then expand and explore them in fiction. One example in this novel is the idea of copies and originals. The woman in A Lover’s Discourse is working on a documentary about a village in China where laborers make imitations of famous works of Western art. Guo in fact did make a documentary, Five Men and a Caravaggio, that hinges on a copy of Caravaggio’s John the Baptist made in the village of Dafen, where copies of classic paintings are a major business.

What is a copy, though? Are the imitated paintings less real? The novel’s title is a coy answer, itself a copy of Roland Barthes’s meditative volume A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments, which indexes fragmented thoughts and tropes in the mind of someone in love. About halfway through Guo’s novel, the protagonist—who loves Barthes’s A Lover’s Discourse—learns that Barthes was never known to have had any serious relationship at all, and that his affairs tended to be with men. In that moment, Guo’s “copy” of Barthes’s work becomes clearly tongue and cheek; a version for the Mandarin-speaking Chinese woman in love with a Western man during Brexit—a lover likely outside Barthes’s imagined audience.

Although the couple compromises and finds a definition of home that suits them, the central question about mutual comprehension is left unanswered. Perhaps it is like Barthes says at the very beginning of his version: “The lover’s discourse is today of an extreme solitude.”

FICTION

A Lover’s Discourse

By Xiaolu Guo

Grove Press

Published October 13, 2020

[ad_2]

Source link