[ad_1]

There are two elements to playing a good cover song. The first is that the band must remember what made the song great in the first place: don’t rewrite the whole song, don’t forget your roots, don’t venture too far from the original. The second (somewhat contradictory) element is that the musicians need to add something new—if only something subtle, a change of key or of instrumentation. A good cover (and there is a huge amount of ground between a clever reinterpretation of a classic and a rip-off) allows the listeners to hear the song anew, bringing to light dimensions of the material which were less developed the first time around.

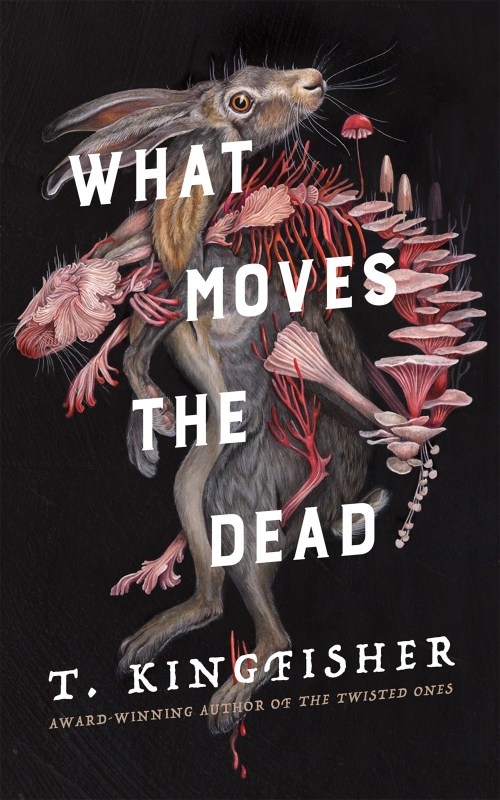

What T. Kingfisher’s latest novella, What Moves the Dead, offers is a transposition of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher” into the territory of contemporary identity politics and, at the same time, the body horror subgenre. Poe’s tale describes its unnamed narrator’s visit of Roderick Usher, a reclusive childhood friend who lives in the crumbling manor house of his family and suffers from a mysterious and chronic illness. As Roderick announces that his sister, Madeline, has died, the pair agree to lay her in the family mausoleum for a period of observation in order to allay Roderick’s fear that Madeline may not in fact be dead, and therefore rule out the possibility of burying her alive (a perennial concern amongst the inhabitants of Poe’s tales). As Madeline rises from the mausoleum—alive, undead, or otherwise—the Ushers die together in a macabre embrace, and with them, their ancestral home collapses, hence the double meaning in the tale’s title.

In Kingfisher’s hands, easily overlooked elements of Poe’s original setting, and previously-underdeveloped characters—the backup vocalists, as it were—are given their own time under the spotlight. Poe’s small cast of somewhat two-dimensional personalities is fleshed out and repurposed: Kingfisher’s Rodericks become more complex (and therefore more human) with the development of their familial backstory and the interaction between the siblings, Poe’s nameless narrator becomes the queer veteran Alex Easton, presumed lover of Madeline Roderick. An American doctor and a female English mycologist seeking to break into the male-dominated world of British life sciences round out the cast. The fungal growths which proliferate around the Usher manor perhaps gain the most from Kingfisher’s retelling, going from mere description to essentially being a character in their own right, one which plays the solo over the tale’s final act.

By choosing to keep the majority of the dialogue in a relatively contemporary tone, Kingfisher is able to lend the tale a certain warmth and sense of humor. This serves to heighten the effects of the horror as the tale progresses; after more than a century of ‘cosmic horror’ fiction which aims at depicting the ‘nameless dread’ of their protagonists encountering forces beyond their comprehension, such strategies have become less effective. The interactions and relationships between Kingfisher’s version of the cast allows the reader to invest in the story in a way the original did not, and invested horror is almost always going to be more effective than the detached, ‘cosmic’ variety.

Similarly, Kingfisher’s decision to historicize the tale is a good one. By emphasizing the rapidly changing culture of the 1890s, especially as regards the medical and scientific worlds, Kingfisher is able to draw upon a classic Gothic trope by reframing the story as a clash between knowledge and the unknown. (The 1890s were, after all, the time of Stoker’s Dracula, another story which ultimately pits the cutting-edge science and technology of its day against a nature of a wholly different kind.) Kingfisher’s references to key events in medical history, such as debates on the gendered nature of hysteria in France which would eventually lead to the establishment of modern talk therapy, also serve to highlight the political concerns of her work.

Where Kingfisher’s version of “The Fall of the House of Usher” runs into dissonance with the original lies, for the most part, in her decision to restage it in two fictious locations. Part of Kingfisher’s conceit is reframing the original characters in reference to the proud but hapless nation of Gallacia, the home country of Easton, whose only export beyond its soldiers is its intricate and expansive set of pronouns. While this choice of setting is sometimes a useful set-up for Kingfisher’s sense of humor—many of Easton’s jokes are self-deprecating, in that they make fun of Gallacia’s many ironies—it is more often distracting and feels like a second book project has been superimposed on the first. It is clear that Kingfisher is trying to do with Poe and gender what Victor LaValle did with Lovecraft and race in The Ballad of Black Tom or what Margaret Atwood did with Homer’s Odyssey in The Penelopiad; this lens, however, neither reflects upon the original nor furthers the story she is trying to tell with it, no matter how often she beats that particular drum.

As Kingfisher writes in her afterword, her own reading of Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s Mexican Gothic was pivotal in her plotting of the second half of What Moves the Dead. While Kingfisher’s mushrooms can keep up with those of Moreno-Garcia in the skin-crawling stakes and provides the book with its finest body horror moments, in its latter stages the novel feels like a cover version of Mexican Gothic just as much as it does a reinterpretation of Poe’s classic tale. Given that Kingfisher’s work to date also includes a revisionist reinterpretation of a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale, as well as an homage to an Algernon Blackwood story (which Lovecraft described as scariest thing he’d ever read), it becomes clear here that Kingfisher’s repertoire is in danger of being dominated by its cover tracks. This would be a shame, as Kingfisher’s strengths—the sense of humor which emerges from her character’s dialogue, the pervading creepiness she conjures via suggestion, and perhaps above all her creatures—warrant a stage less encumbered by the works of others.

While long-time readers of Poe might therefore run into difficulties with the liberties Kingfisher takes with the original, fans of contemporary body horror are likely to find the tale compelling, especially where it delves into the interpenetration of various human, plant, and supernatural bodies which the story relates. Creating a pervasive sense of the uncanny is one of Kingfisher’s best skills; by working between these categories Kingfisher gives the tale its strongest moments.

FICTION

What Moves the Dead

T. Kingfisher

Tor Nightfire

Published July 12th, 2022

[ad_2]

Source link