[ad_1]

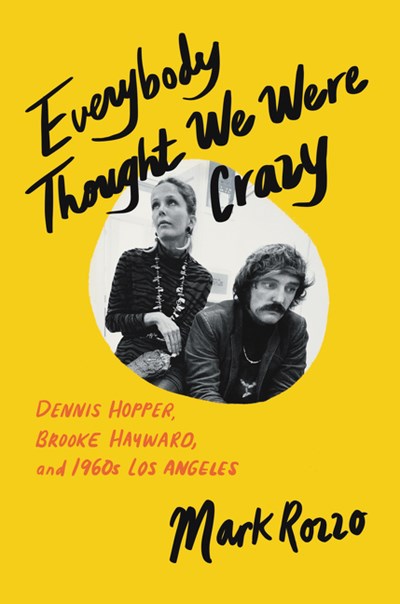

Brooke Hayward describes her years married to Dennis Hopper as “the most wonderful and awful of my life.” In Mark Rozzo’s hands, this goes double for the 1960s, a decade their marriage almost perfectly spanned. His new book Everybody Thought We Were Crazy is an exhaustively researched portrait of Hopper and Hayward’s marriage as a lens to view the ‘60s as a whole.

Everybody Thought We Were Crazy begins by dropping us into the couple’s Los Angeles home as Hayward, a New York transplant, wrestles with a case of the “Transcontinental Blues,” and Hopper is absent on one of his frequent unannounced disappearances. No real introduction precedes this scene, no statement of personal interest or explanation of how Rozzo chose his subject—there doesn’t need to be. This book is essentially a fairytale, a marvelous love story with cinematic ups and downs and a cast of thousands, so it makes sense that it opens like a novel or a film, in a bedroom. This love story, to be fair, does not have a happy ending, or even a happy middle, which you already know if you are aware of Dennis Hopper’s violent persona or have read Brooke Hayward’s bestselling 1977 autobiography Haywire. But Rozzo uses it as a lens to capture the events, innovations, and turbulence of 1960s America, a decade which the Hopper marriage neatly bookends.

Mark Rozzo is a frequent contributor to Vanity Fair, and his articles there have been heavily cribbed for this book. That’s fine; if I had read the original articles there I would certainly have been left with a thirst for more research into the exuberant Sixties, and Everybody Thought We Were Crazy manages to keep up their engaging pace. I suppose magazines like Vanity Fair and The New Yorker are designed to grab you instantly when you flip them open in a dentist’s waiting room, and Rozzo’s book is just as engaging and rewarding to a desultory reader as to a more programmatic one. As I read this book cover to cover, I found myself flipping ahead from the early Sixties to land on a surprise appearance by the Jefferson Airplane, and as I neared the end, I treated myself to reliving an early party with Marcel Duchamp and Vincent Price, and some eyebrow-raising sexual experimentation with Hopper’s castmates from Rebel Without A Cause.

(I hate to center Dennis Hopper here; although he is likely the more recognizable name and certainly has a longer resume, Rozzo emphasizes that he benefited from his gender. Despite the Sexual Revolution that was underway, Hayward remained largely relegated to mothering while Hopper traveled, and philandered, extensively, sometimes documenting his extramarital trysts on film. The two had met on the stage, and while their performances [in a Broadway production of Mandingo, a historical sidebar almost too weird, like much about the Sixties, to be true] were equally lauded, Hayward was discouraged from pursuing a career by her paternalistic father. Nonetheless, she contributed an autobiography in later years that would redefine the genre, being one of the first to account for the role of mental illness in the family. Haywire notably omitted her years with Hopper, and it is this cipher that Rozzo seeks to fill.)

I came away from this book in awe of Hopper and Hayward, not so much for their considerable contributions to their arts but simply for their serendipity and seeming ability to have experienced firsthand everything the ‘60s had to offer. At times the book feels unreal because it resembles films like Almost Famous or Forrest Gump, whose hapless protagonists accidentally stumble into every defining event of their generation and fortuitously find themselves at parties with its brightest lights and scions. But so it was—and it is a delight to read about. Dennis Hopper started his career alongside James Dean, and helped launch Andy Warhol’s career, purchasing some of the artist’s very first prints of a Campbell’s soup can (much to the derision of his High-Art-loving houseguests). His living room floor played crash pad for movie stars and Hell’s Angels, as he befriended everyone from David O. Selznick to the Beatles and the Byrds. I was surprised to learn he photographed Ike and Tina Turner for one of their album covers. And to think, this book doesn’t even touch on Hopper’s punk rock filmmaking in the 1980s or his rebirth as one of cinema’s most memorable villains in David Lynch’s 1986 film Blue Velvet. One suspects the making of Easy Rider alone, which receives only a few pages in Rozzo’s book, would merit a book of its own.

Everybody Thought We Were Crazy, for all its dizzying glory, has a sad ending. Hopper, who once described his oeuvre as a “river of shit,” descended into violence and drug addiction, survived rehab, and emerged as “a well-groomed, sober Hollywood star who now embraced right-wing politics, an about-face that bewildered his friends.” His story is the story of his generation in a nutshell: the cliche of ‘60s stoned idealism giving way to ‘70s cocaine-fueled violent nihilism, and maturing into Ronald Reagan’s 1980s.

That this nonfiction book reads almost like a magical realist fairytale is not surprising, given the rather fantastical nature of its subjects. Singer Kris Kristofferson said of Hopper, “He’s partly truth and partly fiction.” (This in his song “The Pilgrim, Chapter 33,” which explicitly states that it was written about Hopper.) Justifying Hopper’s childhood ambition to leave his hometown and move to Los Angeles, Rozzo explains that “Kansas was a dream. Hollywood was real.” Everybody Thought We Were Crazy is one hundred percent true, exhaustively researched, and yet more similar to a delirious romance movie than anything our sad, quotidian lives will ever contain.

NONFICTION

Everybody Thought We Were Crazy

By Mark Rozzo

Ecco Press

Published May 3, 2022

[ad_2]

Source link