[ad_1]

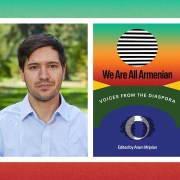

Ghost Pains is author Jessi Jezewska Stevens’ third book and first story collection. Propulsive, reflective, and at times sharply comic, Stevens’ short fiction is characterized by her precise, original prose and striking moments of observation and insight. The protagonists of her stories, equal parts aloof and earnest, at times resemble the leads in her two novels—alienated, bewildered Percy in The Exhibition of Persephone Q (2020) and C, preoccupied with a poltergeist (and economic collapse) in The Visitors (2022)—all while remaining completely their own. These women navigate ex-pat environments across Europe, throwing parties in Berlin, honeymooning in Italy, playwriting in a city where conflict rages in the streets. They are Americans who feel like foreigners while on a road trip in the States, in a distant relative’s home, or visiting the rural studio of a reclusive musician.

As I read through the collection’s eleven stories, which have appeared in The Paris Review, Harper’s, and more, each new narrative became a new favorite and deepened my understanding of the others. The stories in Ghost Pains build upon one another to ask incisive questions about how we live today: interpersonally, economically and politically, and morally.

Stevens and I connected over a video call in January. We spoke about defamiliarization, the satirical versus the absurd, interconnected themes of debt, trash, and cleanliness, and more.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Regan Mies

A few of the stories in your new collection, Ghost Pains, take place in suburban or rural US settings, but the majority are set in Europe. Your two novels, on the other hand, are very strongly grounded in New York City—The Exhibition of Persephone Q in a hazy post-9/11 Upper West Side and The Visitors downtown during the market collapse of 2008. I wanted to ask about that shift in setting from your novels to your short fiction.

Jessi Jezewska Stevens

I’ll start with what I think is consistent between the novels and the stories, which is the attitude or worldview of the narrators.

I’ve been thinking about this because there’s been so much talk of disaffected young female narrators and alienation in anglophone fiction. There is something going on, and I can recognize this trend and a lot of the wonderful writing that’s come out of it, too. I haven’t recognized it as precisely in my own work, however, because I see my own narrators—across all three books—as pretty normie strivers who actually really want to integrate into their immediate surroundings. They want to play by the rules of meritocracy and self-invention, and they’re trying to, they’re just really bad at it. With both my novels and stories, I think I’ve always been interested in the dramatic potential of the moment in which someone’s worldview—in particular this worldview—begins to fall apart. I have these characters who have the ambition to integrate into their immediate environments and to participate, who still think the world works according to these rules, but we meet them at exactly the moment when they’ve discovered that in fact this is not the case. And then everything becomes strange because that worldview is beginning to disintegrate.

The dramatic potential of this moment of defamiliarization is what I’m fascinated by psychologically. I also think there’s a comedic potential in those moments. And as is the case for a lot of people when trying to make sense of something really difficult, humor becomes a coping mechanism. So I would frame the stories and the novels as being about people who are having the rug pulled out from under them. They’re in denial about the fact that it’s happening, and they’re trying to gain traction and keep up with the fact that the rules have actually changed—or maybe there were no rules to begin with.

I think of Americans and American society as suspended in this very gaslighting state of “strive and do these things, and you will improve your lot,” and, you know, “screw everyone else.” Or at least being culturally gaslighted into that individual striving, only to find out that the rules work differently, is one kind of archetypal American experience. The basic defamiliarization inherent to being an ex-pat in the stories is maybe an extension of this. It’s showing up and realizing, I have to update how I think things work.

Regan Mies

Many of your stories drift into uncanny, dreamlike territory. The narrator of “A New Book of Grotesques” encounters her ex-husband on the street in Berlin, even though he was supposed to be a continent away. Then she’s on an overnight train, and her old roommate from years ago coincidently has the bunk above her but doesn’t recognize her. The narrator of “Letter to the Senator” melts through the floorboards at the end of a dinner party. Your characters have ideas of how things are supposed to be, and suddenly, their surroundings become unfamiliar. Inexplicable things occur yet remain unquestioned. From a craft perspective, could you talk more about your decisions behind those surrealist techniques or devices?

Jessi Jezewska Stevens

Summarized that way, I’m reminded of Bergson, who has that definition of the comedic as the interrupted mechanical action. He uses some example like a man with the top hat who is properly dressed and properly behaved suddenly slipping on a banana peel. And it’s funny because it interrupts the kind of unconscious, mechanical, often pompous way we move through the world.

When those slips become exaggerated even more by an absurd or a surrealist twist—I feel like there’s something especially comedic but also unsettling about that. And then there’s also an argument or a thematic function regarding those decisions: to exaggerate the way in which we’re dramatizing shifts in worldviews. I love narrators who, caught doing something stupid, turn out to be accidentally wise.

Regan Mies

Talking about absurdity in your fiction, I have to bring up “Rumpel,” your story about a virtual reality gaming company and a crypto enthusiast. The story features an elf-like trickster character who speaks in binary, and your novel The Visitors also features a gnome-like apparition who hovers around the main character and talks finance. I’m curious what this juxtaposition is all about—between something “serious,” like big tech or market economics, and the icon of a strange, mystical creature.

Jessi Jezewska Stevens

I guess in a previous life I did study and work in math and economics, kind of because I was too afraid to study literature. The people who studied literature when I was in college were much more cosmopolitan, much better prepared. I didn’t feel I could keep up. And I have a natural fascination with economics, tech, but I’m also very fascinated in the psychology and storytelling that goes into markets, in that kind of projection, so the apparent separation of the “worlds” of quant and literature aren’t so separate for me. It remains a sort of pet interest. It remains a world that I know. We all have our influences.

I also just love fairy tales. I grew up reading them. By the time I was ten, I’d probably read all the Lang Fairy Books, in addition to Grimm’s and Greek myths and Kipling. I had these anthologies of fairy tales and origin stories from around the world, and I had tapes from my grandfather who—because he knew he was going to die when I was still very young—recorded a bunch of French folk tales for me on tape that I used to listen to before I went to sleep. (He was a big Francophile.) I was just steeped in this, so there’s probably something of the fairy tale that lingers in my work. Also, when you grow up as an only child in the woods, as I did in the Adirondacks, those stories sort of spill over into the landscape.

And I don’t know if fairy tales work with straight satire, so maybe that also is a reason I prefer to write about the world with a more absurdist or fairy-tale, rather than a “satirical,” twist.

Regan Mies

Another similarity I noticed between The Visitors and Ghost Pains is debt as a theme. In “Weimar Whore,” a woman transforms into a character from a very specific time and place; she invites a boarder to sleep on her couch, worries about inflation, stews cabbages, and things escalate from there. At the story’s conclusion, you write that cities are built on trash and debris but that it might as well be said that they’re built on debt. What makes this theme of debt so ripe for fiction? The cyclicality of politics, the economy—or something else entirely?

Jessi Jezewska Stevens

It’s funny, I’m always writing stories on the side while I’m working on novels, so they kind of track these other preoccupations. I would hate to say that I workshop ideas for novels in stories, because it doesn’t feel that way. It feels like . . . I guess “B-side” would also demote them, but there is some kind of resonance there. I remember when I was writing the end to that story my editor was like, “Is this too close to The Visitors?” I wrote “Weimar,” right when The Visitors was coming out, and it was still on my mind.

As for the description of debt . . . I guess it’s just true, so why wouldn’t I write about it? We know it so well that it’s boring. But maybe it feels surprising when that idea comes at the end of a story that feels slapstick for a few thousand words, and then suddenly feels a bit darker or more unsettling. Then we recognize the abyss again.

“Rumpel” started when I was talking with my husband and some friends after I read an article about this guy who lost his Bitcoin password and was going through these landfills searching for it. He had, like, 200 million dollars in his account, and the whole thing is this Ponzi scheme anyway—it was just this amazing headline, and we were riffing, and I got on this Rumpelstiltskin thing about how this guy couldn’t find his password. So, it started as a joke, and then it became a world.

Regan Mies

Along with debt, trash and dirtiness are recurring, intertwined themes throughout your stories, and so are characters really wishing for and desiring cleanliness in response. I’m thinking of Tina, the main character in the titular “Ghost Pains.” She’s a headhunter at a tech conference in Poland, and she’s also helping an ex navigate Polish bureaucracy so he can receive his inheritance from his recently passed grandfather. At the same time, there’s this joke-like aspect, like you mention, where Tina’s dealing with an infected nipple piercing. Throughout the story, she finds herself wishing more than anything for a “deep, internal cleanse.” And then, in “Letters to the Senator,” party guests draft letters to their senator before ultimately tossing all these scraps aside. The narrator observes that the group needs “a hint of ammonia or bleach to clear the neglected plumbing of our souls.” I wanted to ask what you think: Is there a way for us to cleanse ourselves, as individuals or a society, or as readers, writers, artists? Do we need to?

Jessi Jezewska Stevens

No. I mean, I think it’s a preoccupation, but I don’t think it’s possible or desirable. That’s why I’m so interested in it.

I like this question though, because it gets to what might be one of the more contiguous threads in the book, which is relationships to history and the characters’ shifting relationships to history. They’re looking at history in new ways in a lot of these stories. You’re a millennial . . . or are you a Gen Z?

Regan Mies

I’m at the cusp? I think I’m more Gen Z. I pick and choose.

Jessi Jezewska Stevens

Generation-curious. I mean, I don’t know if it’s unique, but as a solid millennial, I do think that at least in our (American) generational moment, a lot of the social issues that we have dealt with revolve around this idea that we can clean up history, clean ourselves of history, or do better than previous generations. I think it’s incredibly important to hold on to the idea of social progress. We ought to try to do better than previous generations. That’s important. On the other hand, I think there are some things that simply can’t be reconciled. Things that just . . . stay stains on human history forever. I think my characters begin these stories naive about their personal histories or, in that titular story, about broader histories. That story gets into restitution law in Poland, for example. Or in “Weimar,” I was thinking about how hysterical it is (or isn’t) to draw analogies between the Weimar era and our times—how hysterical and how fetishistic.

Things that happened in the past, on the one hand, they seem like they have nothing to do with you; you’re of a new generation. On the other hand, they have everything to do with you, because things that can never be truly atoned for or reconciled continue to emit these . . . energies in the present and influence the way we relate to each other. That motif of wanting to be pure and wanting to be a good person is dramatized maybe in the discomfort these characters have with being historical beings, with the idea of history, and with the idea of inheritance.

One more thing on the trash motif I’m reminded of: I feel like in contemporary fiction there’s rightly a lot of discourse about how all of our stories circle around the drain of “late capitalism.” But I’m equally if not more interested in the flip-side logic of consumerism, the idea that we don’t really shape our worlds anymore. We just exercise our preferences amongst preset options or exercise our purchasing power. And then we consume and expend, and then we have all this trash. And this idea of waste, maybe, is also an American preoccupation. Or at least an American state of being. We’re famous for waste. But there’s this weird way that, because it’s trash, because it has no use-value, it’s outside the logic of capitalism, and also kind of . . . temporally static. It’s one of those last spaces where you can be like, What can I do with all this trash? Literally or figuratively. And on your own terms. Maybe there’s some creative potential there in trying to do something more human or beautiful with it. I think it’s there in the stories, definitely in The Visitors, and then in my first novel, The Exhibition of Persephone Q, Misha has a metal detector and he’s constantly collecting trash. . . . So yeah, that is a preoccupation.

Regan Mies

You’ve also written on topics such as degrowth economics, climate change, and nationalism for Foreign Policy, among other publications. Do you ever find that your nonfiction writing directly inspires your fiction or vice versa?

Jessi Jezewska Stevens

Definitely. I don’t know if I have a grand theory, but even just that motif of trash is an example. When I’m writing about climate movements in Europe, or about climate policy, I’m preoccupied with technocratic relationships to waste. But the literary part of me is fascinated by the spectacle of it. I think it’s easy to underestimate how fascinating it is to learn something from fiction, too. It’s attractive when there’s a bit of expertise about some niche on the page. When you go into a deep dive into a climate activist world—or, I’m writing something about Vienna right now—you’re so steeped in the detail and know-how of a subculture that it becomes fascinating in itself. I think that in order to write nonfiction, or at least the kind that I write, you should be deeply curious, a listener, and I think that’s also the orientation I have towards my subjects when I’m writing fiction.

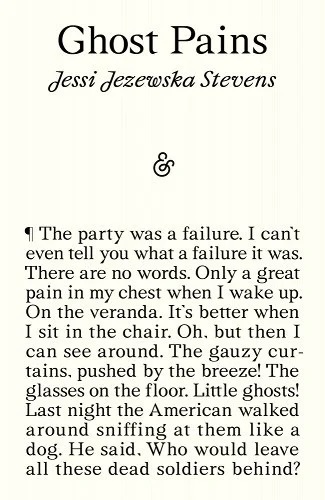

FICTION

Ghost Pains

By Jessi Jezewska Stevens

And Other Stories

Published March 5, 2024

[ad_2]

Source link