[ad_1]

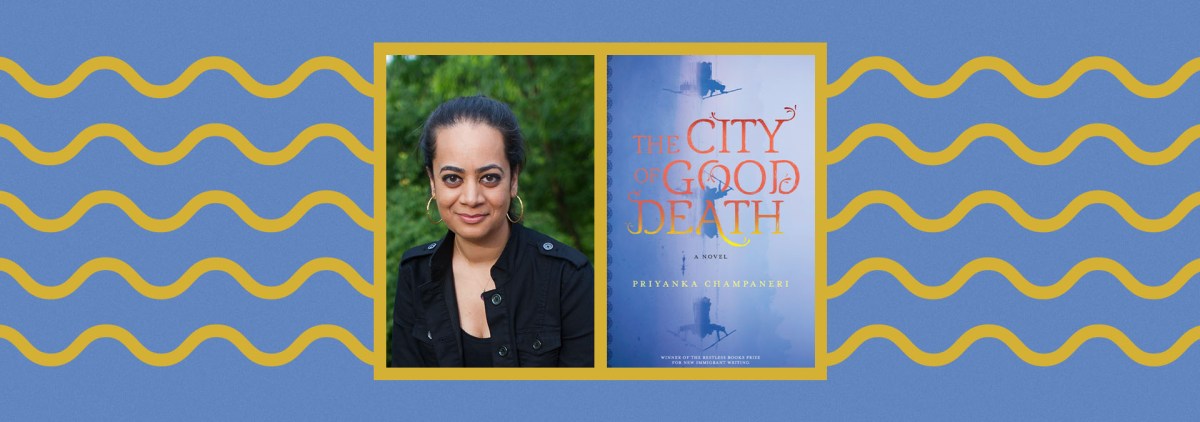

Priyanka Champaneri’s enthralling debut novel, The City of Good Death, winner of the 2018 Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing, is a heart-warming read about a city where people come to die in peace and the beauty of being alive, enhanced by the unapologetic presence of death in the lives of its characters.

Set in the holy city of Kashi, India, Champaneri’s novel tells the story of a death hostel manager, Pramesh, who left his village for a new life years ago. The story commences, however, when the dead body of Pramesh’s cousin is found in Kashi, and takes us to their childhood in a small village.

I asked Priyanka Champaneri about what happens after one wins such a prize, the role gender plays in how different characters navigate the loneliness of life and death, and how having spent eight years writing a novel set in “the city of good death” makes her view the times we live in.

Nazli Koca

Congratulations on winning the New Immigrant Prize! Can you tell us about the origin story of The City of Good Death and what made you submit it to the contest in 2018?

Priyanka Champaneri

Thank you so much. In 2005, a friend sent me a Reuters article about the death hostels in Banaras. I had grown up in a Hindu household, and so I had a faint recognition that Banaras was an important city, but the death hostels were entirely new to me. The thought of setting a story within such a place immediately came to mind, but I didn’t act on it for many years for a few reasons: I didn’t think I was capable of doing justice to the idea; I lacked experience with that part of India; and my own identity as a Gujarati—not a Banarasi—born and raised in the United States created even more barriers which made me wonder if I was the right person to tell that story. But the idea always remained in the back of my mind, and I found myself drawn to absorbing anything I could find on Banaras. The more I read, the more various characters started to emerge and assert themselves, and I felt the gaps in my knowledge—gaps that had prevented me from deciding to write in the first place—being filled, until I felt comfortable enough to begin.

By the time I decided to enter the Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing, I’d spent about eight years writing and revising a draft, finding my fantastic agent, Leigh Feldman, and receiving rejections from almost every tier of the publishing industry. My motivation for entering was to simply shut that final door for myself so I wouldn’t have any regrets years from now about giving up too soon. I forgot about the submission until months later, when in the fall of 2018 I received the email that I’d won.

Nazli Koca

You said you’ve never been to Banaras (Kashi) yourself, but your descriptions of the city are extremely vibrant. More than once, I found myself lost in the streets of Kashi, tasting the food its people were eating, smelling the scents of its streets. Clearly you’ve put a lot of work into the set up.

Priyanka Champaneri

This is an incredible compliment. I’ve visited parts of India, but I have yet to physically visit Banaras, so perhaps I was creating the city for myself just as much as I was for the reader. I dove into everything I could find on Banaras—film, photography, ethnography, memoir and fiction, even YouTube videos uploaded by travelers walking through the city’s narrow alleys. I was really hungry to find visuals—not just the famous scenes of the crowded ghats that many people are familiar with; but, also, pictures of daily life, empty alleys, anything to give me a sense of place so I could envision it fully in my mind. All of the research was helpful to a point, but I also relied on my memories from my travels in India: small details that you can’t learn from books, things that have stayed with me and seem to be universal no matter where you go in the country—the market lanes, the smells and sounds, the quality of banter. All of it just goes into the mental well, and then when I sit down to write it’s a matter of focusing on the story and hoping to recall the right piece when I need it. When the writing is flowing, it feels like a scene from a movie scrolling before my eyes, and my job is to keep up and record it all faithfully.

Nazli Koca

I loved the ways in which Shobha and Kamna overcame the loneliness of womanhood. The novel does a painfully beautiful job portraying how gender roles can push women into isolation, especially in closed societies. Likewise, codes of masculinity can stop men from forming or nurturing genuine relationships. What are the differences between the way men and women choose to deal with this in the world of your novel?

Priyanka Champaneri

Any gender or class-based society is going to attempt to box people into a standard of behavior governed by strictly ingrained rules. What’s interesting to me is how individuals react within those boxes, the ingenuity and the weakness that can emerge. For men, there’s great freedom and the ability to abuse or be generous with that power, but it can come with the trade-off of being unable to communicate emotions or to see beyond the boundaries of the “right” way to do things. Whereas women, who often have little to no latitude within their box, can create these intensely robust internal lives based on observation and emotional acuity. And those abilities can allow them to be the masters of every social interaction they have—observing the mood and the moment, deciding whether to speak or stay silent, being meticulous in their choice of words. So Pramesh, stricken by grief and overwhelmed by resurging memories of his past, is unable to goad himself into action because he’s so intent on avoiding a scandal that will harm his family’s reputation. Whereas Shobha is able to quietly investigate on her own and try to make sense of what she’s remembered and learned, because she’s surmised that the thing troubling her husband isn’t likely to go away on its own.

Nazli Koca

You wrote a very long novel—a surprisingly long novel for a debut, even though it is a widely known fact among writers that the longer your debut is, the harder it will be to sell it. What made you stick to the length, and the form of your novel in general, against all odds?

Priyanka Champaneri

It never crossed my mind that a lengthy debut might be a problem for publishers—I didn’t know any better. My earlier drafts were much longer and had more characters, more secondary plot lines, lengthier scenic descriptions. I absolutely assumed—naively, I think—that if I did the best I could and looked at the book as objectively as possible before sending it out, someone would come along and want to publish it. Knowing what I know now, I’m not sure I’d have the same confidence about submitting a long manuscript for a debut.

Looking at my history as a reader, it might have been inevitable that I would write a long book. So many of my favorite reads are long and epic, with many characters and numerous plot strands that weave in and out. Anna Karenina, Midnight’s Children, A House for Mr. Biswas, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, and my ultimate desert-island book, A Suitable Boy. These are all books that give me the thrill I’m looking for as a reader—the feeling of being so completely immersed that you feel as if you’ve suffered a grave loss when you finally finish reading—you just never want the experience to end.

Nazli Koca

What has changed in your life and writing career since you won the prize?

Priyanka Champaneri

The writing lessons I’ve learned have been profound. When I started, I was very focused on this idea of “writing perfect”—meaning I’d constantly go back and comb through what I’d already written, fixing everything on the line level in a very focused way, before I allowed myself to start writing for the night. Shocker: so much of what I’d meticulously labored over in those early years ended up on the cutting room floor during the revision process, both when I was revising on my own and while working with my editor Nathan Rostron. Working with Nathan was like novel-revising boot camp—nothing gets past him. He caught every plot loophole or gap in logic and prompted me to reach deeper by asking me questions as a starting point for filling those holes. I learned more about the value of a clean line, of balancing between lyricism and clarity. And I’m now a firm believer in messy drafts, in just dumping it all out on the page and letting the story propel me forward, knowing there will be a time for fixing it all much later down the line.

Nazli Koca

Do you feel that working on a novel in which dying plays an equal part as life for eight years made you view the Covid crisis differently than most of us?

Priyanka Champaneri

Writing a book on death is not the same as experiencing it personally. It’s one thing to look at death on an abstract level—it’s the universal leveler, inevitable and unyielding, whether it comes via the pandemic, old age, or otherwise. But it’s another thing to look at a specific life and feel the brunt of grief associated with losing everything that person brought into the world, and knowing they should have had more time.

The defining image of the pandemic for me has been that of a person dying in a hospital, saying their goodbyes to loved ones over a screen, with only an essential health care worker clad in PPE present to serve as a witness and provide comfort in those last moments. And of families denied their specific mourning rituals as part of the grieving process. This period in human history is going to leave a lasting dent globally not only because of the lives lost; but, also, because of the psychological and emotional trauma for the ones left behind.

FICTION

The City of Good Death

By Priyanka Champaneri

Restless Books

Published February 23th, 2021

[ad_2]

Source link