[ad_1]

A general move that most fantasy has made, perhaps most fiction has made, is to zoom in, to show more, to unpack rather than summarize. Where a fairy tale or earlier fiction might just say “they traveled for a month,” the more modern approach is likely to tell you what that felt like, what they wore and ate and thought about, the weather or the landscape,letting detail and conversation fill pages. There seems to be a general writerly drive—or readerly desire—to fill in, expand, tell more. “Show don’t tell” writ large, an attempt to capture the emotional significance by getting really close, with human observation. As Alexandra Erin notes, it’s why there is a real sense in which Twilight is better written than Dracula; it’s why even quite faithful retellings—Madeline Miller’s Circe springs to mind—can succeed: by stepping closer, decompressing, making obviously fictional archetypes less mythic, more human.

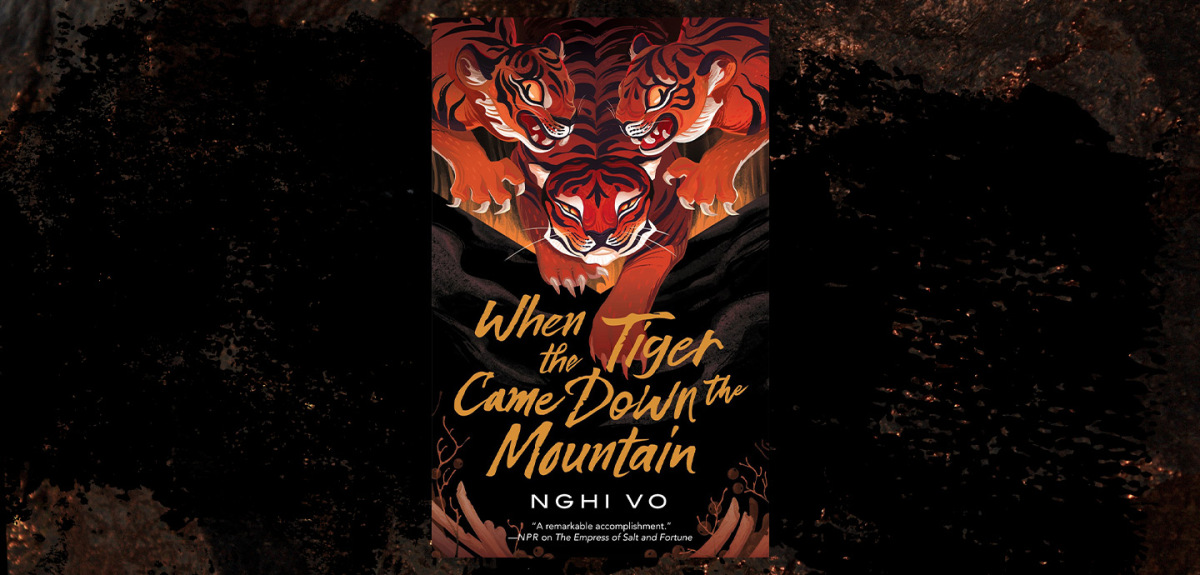

Given that impulse, Nghi Vo’s When the Tiger Came Down the Mountain is masterful in its ability to step back, to allow the fairytale stay in its frame, at a bit of a distance from the immediate action. That refusal to humanize more than warranted works hand in hand with the space that Vo gives for the non-human—even when it walks and talks a bit like a person.

The novella is a sequel to The Empress of Salt and Fortune, but certainly doesn’t require reading that first. Set in a fantasy world inspired by Chinese history, it again follows Chih, a cleric from an order focused on recording history, as they travel—by mammoth!—into the chilly northern country. Ambushed by a trio of shape-shifting tigers, Chih and their mammoth-riding escort, Si-Yu, find themselves with nothing but a story to keep these polite but hungry predators at bay—a captor, rather than captive, audience. The immediate, detailed story thus recedes to a frame around the story of the tiger Ho Thi Tao and the human scholar Dieu: a love story presented as historical, but with obvious shadings of fable.

Chih learned the human version of the tale, while the tigers know their own; much of the excellence of When the Tiger Came Down the Mountain is in how the novella plays up this contested retelling. Although the two versions of the tale differ more in detail and tone than in the basic outline, the tigers are at turns affronted and intrigued by the human “errors” in Chih’s story, and so—despite the threat of violence never far beneath the surface—find themselves drawn into a revising process: for honor, for accuracy, and, increasingly as they invest themselves, for the sake of a good story. “‘There is an addition for your books, cleric. Make note of it so that they will find it after we eat you. Please continue.’”

The novella’s structure echoes One Thousand and One Nights, with the act of careful storytelling staving off death. The story is also reminiscent of Trickster traditions, like Coyote or Anansi, or Gandalf tricking Beorn and the trolls in The Hobbit—smaller, weaker characters relying on cleverness, and using story itself to pull even their villains into the audience. The tigers’ correction of the tale—often changing entire plot points, but sometimes charmingly minor, as when they point out that Ho Thi Tao’s offer to let Dieu try to run away was kind, not callous—is less about there being two sides to the story, and more about getting the tiger back in.

Maria Dahvana Headley’s The Mere Wife and Beowulf translation have monsters on my mind of late. As Tolkien said, “Beowulf’s dragon, if one wishes to criticize, is not to be blamed for being a dragon, but rather for not being dragon enough.” One of the many points of brilliance in When the Tiger Came Down the Mountain is the space and voice Vo gives to the non-human, in how she lets them be tiger enough. Yes, they talk, may walk upright for now, but, like Waterson’s Hobbes, they never hesitate to remind us that humans’ real purpose is to be tiger-food; the tigers voices’ ripple with fierce and catlike hunger, arrogance, and territoriality. The centrality and authenticity of that non-human reality anchors the fantastic elements of the world, from mammoths to fox spirits.

As a piece of fantasy literature, Vo’s worldbuilding is a command performance, if a subdued one. The material reality of the story’s present feels incredibly strong, from the stitching on Si-Yu’s boot to the brief sketches of geopolitics and history. What’s truly impressive is the way Vo weds this firm reality with fantasy and fairy tale. Chih has listened to ghosts, seen a dragon: there’s no sense that the folk tales are false. The novella is rather a meditation on versions of stories, shadings and retellings, the importance of the teller’s intent and insight—and it never dismisses even the most fantastic ideas as “just a story.” The marriage of Ho Thi Tao and Dieu feels like a fairy story even within the novella, but we hear it in a realistic, believable setting—but also, again, alongside talking tigers. These are the folk tales they tell within folk tales.

The novella is also notable for its quiet subversion of gender norms. Ho Thi Tao and Dieu’s story is a love story about two women, though not both human; Chih is non-binary, and these facts pass without comment or judgment. Like The Empress of Salt and Fortune, though, When the Tiger Came Down the Mountain is charged with female agency, with women full of anger, hunger, power. The novella is particularly rich in the polysemy of feeding: as a clear metaphor for sex, as a simple fulfilmment of need, and as violence. It calls to mind the intersection of violence and queer desire in vampire or werewolf stories, like Indrapramit Das’s The Devourers. And yet, there is room for sweetness here, and complexity. The tiger loves the scholar’s beauty, and comes to wonder how the scholar might also be ugly, “which could also be fascinating and beloved.”

What I find delightful about When the Tiger Came Down the Mountain is how it’s willing to let the frame stand, and to use it. While “The Marriage of the Tiger and the Scholar” might be “true” within the world, it’s treated somewhat like a folk tale, and there are gaps, different versions and interpretations; the novella never jumps “all the way in” to give us what Ho Thi Tao or Dieu “really” experienced. We never forget that this is a tale being told—and that very distancing allows for emotional punches within the tale, and a heightened sense of reality without. When Dieu shares her favorite poem with the tiger, we’re told that “when you love a thing too much, it is a special kind of pain to show them to others and to see that they are lacking”—a line that would feel forced or saccharine in the narrative of the frame story, but which feels utterly natural, and powerful, within the retelling. Likewise, the contrast of the mythic figures in the tale cements the ordinariness and hence believability of Chih and Si-Yu, and, while we get very little personal detail about either of them, much less the three tiger sisters, Vo accomplishes just the right amount of characterization in how each of them react to the story being told.

It’s a bit hackneyed to observe that there are enough ideas here for a much longer work, and it’s delightful that When the Tiger Came Down the Mountain is the length that it is. We are in a golden age of the novella, and Vo knows how to make the most of the form, with short, propelling chapters and potent ideas. The world is scaffolded off real history and folk traditions but feels fresh and interesting, and Vo once again succeeds in using a scholarly, contemplative protagonist to tease deep emotion and significance out of old stories. It’s an incredibly, quietly skilled and entertaining accomplishment, and the final scene—a wordless interaction between Chih and another non-human character, this time a mammoth—closes the novella with a strange sense of hope and openness. I hope there’s more to come.

When the Tiger Came Down the Mountain

Nghi Vo

Tordotcom

Published December 08, 2020

[ad_2]

Source link