[ad_1]

In the summer of 2017, when she was feeling particularly overloaded, Anna Funder returned to the work of George Orwell, a writer she had “always loved.” She hoped that by reading his analyses of “the tyrannies, the ‘smelly little orthodoxies’ of his time” she would be able “to liberate myself” and in particular to understand the “motherload of wifedom I had taken on.” After reading his texts, she began on the biographies, moving “from the work to the life.” The drama of Orwell’s adult years, the importance of his autobiographical writings, and his distinctive narrative voice, which leads many readers to feel a personal connection to him, all fuel the temptation to explain his writing in terms of his personality and experience. This has produced some excellent accounts of his life but too often obscures the complexities of his thought and technique.

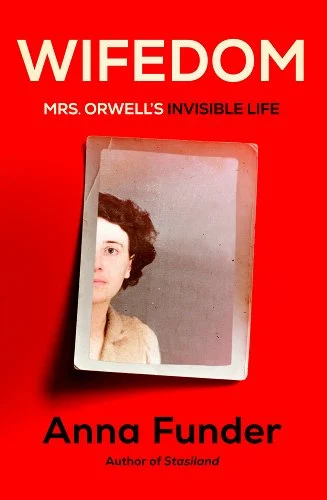

Wifedom by Anna Funder is fortunately not another biography of Orwell; there is an extra step, from the “man to the wife,” and, more broadly, an account of the gendered systems that enabled his writing. The result is an engaging, informative, but flawed book that focuses attention on Eileen O’Shaughnessy—who was married to Orwell from 1936 until her premature death in 1945—but too often speaks on her behalf. Funder insists early in the book that she chose not to write a novel about Eileen because she did not want to “privilege my voice over hers” but this is frequently what she does.

Funder insists that Eileen “hasn’t really been in the biographies.” The word “really” does a lot of work here, but the argument serves a useful and critical function. The major events of her life after meeting Orwell are well known, and some of his biographers have claimed to pay significant attention to her. Jeffrey Meyers, for example, describes Eileen as the “self-sacrificing heroine” of his Orwell: Wintry Conscience of a Generation. Yet, despite this, she largely remains a marginal presence in accounts of Orwell’s life. As Funder emphasizes, this has reinforced the myth of Orwell as a solitary genius, a writer who has “done it all, alone.” She is astute about the mechanics of this process, exposing biographers’ use of passive voice to obscure Eileen’s presence and agency, to literally displace her as the subject of her own narrative. Wifedom puts her at the center of the story. Its careful, detailed reconstruction of her time in Spain, where she worked in the Independent Labour Party offices, is particularly good. As Funder argues, far from merely visiting her husband, she had significant responsibilities, almost certainly “saved lives,” and acted with remarkable courage during the Communist purge in Barcelona. Eileen may have spent much of her married life cooking, cleaning, typing, editing, and otherwise creating the conditions for Orwell to write. But when she had opportunities to do other work she flourished.

One challenge when writing about Eileen is that there are comparatively few first-hand accounts of her and even fewer documents in her own words. The discovery in 2005 of her witty, perceptive letters to her Oxford friend Norah Myles significantly extended the understanding of her thoughts, personality, and voice but there are unfortunately only six of them. Consequently, Funder’s book largely reinterprets and reorganizes familiar information. Orwell’s numerous affairs, which are central to Funder’s argument that he was a neglectful, self-absorbed husband, are already well-known. In contrast to some of the biographies, she insists on the damage they did to Eileen, rejecting his repeated claim to the women he seduced or simply “pounced” on, that she accepted what he was doing.

Funder’s decision to compensate for a lack of Eileen’s own words by reconstructing what she felt is nonetheless a mistake. When writing about Tosco Fyvel’s notorious statement that Orwell claimed he had slept with a young Moroccan woman with Eileen’s permission, for example, Funder describes their conversation, Eileen’s thoughts while she waits, and Orwell’s return home. Funder insists she is using “evidence most biographers omit” but there is no evidence; as she acknowledges, she is “imagining these details.” Insisting that “there must have been some kind of scene” does not justify inventing its content. To question these fictional interludes is not to be complicit in attempts to obscure Orwell’s failings in order to reconcile “‘decent’ Orwell with his actions” but to raise ethical concerns about speaking for someone else. The creative passages imagining Eileen’s reasons for acting and writing as she did have been widely praised in advance notices for the book but are problematic in themselves, not just because the Eileen that emerges from them is less interesting, less assured, and has less agency than the one in the letters.

There is a great deal to admire in Wifedom. It is well-written and, on its own terms, carefully researched, although it is a shame Funder did not consult the extensive scholarship on Orwell, as his ideas about gender and sexuality have been discussed for decades. It has little new to tell us about Orwell but it is not about him; it is about Eileen. The closing chapters, about the period after her death, are significantly weaker than the remainder of the text, as if Funder has simply lost interest. The book is at its best when tracing the details of Eileen’s life, her friendships, and her creativity, but has less to say about some of the broader issues it raises. Funder does not, for example, provide a satisfactory response to the question of “how to think about an author you’ve long loved if you find out they were” an “arsehole.” She does, to her great credit, worry others will answer simply and reductively, and that Orwell, whose work “is precious to me,” might “risk being ‘cancelled’ by the story I am telling.” One hopes, even in the current climate, that will not happen. Orwell was a wonderful writer and a poor husband. The one does not invalidate the other, and his brilliantly original essays are no more compromised by his infidelities than King Lear is by the second-best bed. As Funder demonstrates, being married to Orwell was a difficult, exhausting experience. We can acknowledge that whilst enjoying texts that exemplify the possibilities of political writing and are, like all good works of art, superior to the person who produced them.

The importance of Wifedom fortunately does not lie in its insights into this question or anything it tells us about Orwell’s work, but in its account of Eileen, a keenly intelligent, talented woman who has too often only appeared as a peripheral figure in his biographies. Her life was fascinating and worthwhile in itself; we do not need to see it merely as a footnote to his, nor have Funder tell us what Eileen might have thought or felt, to appreciate its value or the possibilities cut short by her early death.

FICTION

Wifedom

Anna Funder

Knopf Publishing Group

Published August 22, 2023

[ad_2]

Source link