[ad_1]

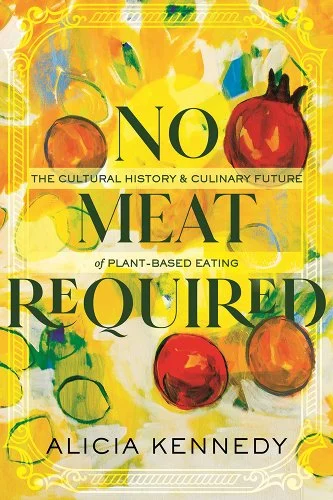

Plant-based diets have in recent years shifted from fringe movements to mass market consumerism. The widespread market penetration of products like oat milk lattes has also meant many omnivores are making vegan dietary choices whether they intend to or not. Although there are ever more vegan cookbooks, there isn’t much about the history of vegan culture, particularly in the United States. That’s the story Alicia Kennedy’s new book, No Meat Required: The Cultural History & Culinary Future of Plant-Based Eating, seeks to tell.

No Meat Required examines the history of vegan and vegetarian cuisine over the last century or so, primarily in the United States, and to a lesser degree, within broader Western culinary traditions more generally. She does cover the intersection of historically vegan and vegetarian cuisines from other parts of the world, but largely as they pertain to the rise of vegan cuisine in the United States. She also notes that Asian-influenced vegan cookbooks have been a welcome addition to the culinary traditions of Western vegan cuisine in recent years.

The book is particularly focused on the shift from the late 1970s, when veganism was more of a niche cult, to today, when national chains and typical supermarkets are hawking Impossible Burgers and vegan dairy products. Kennedy also weaves through this history her own personal narrative, interjecting her experiences shifting from omnivore to vegetarianism to veganism and back again. The interwoven discussion of her personal journey helps contextualize much of the choices people face when making their own dietary decisions. These are choices that are now easier to make in large part because of the various investments in innovating plant-based foods. Kennedy even criticizes modern vegan trends focused on replicating meat while ignoring the beauty of fruits and vegetables–these are naturally animal-free, a point seemingly lost on the food technologists.

At the core of this book is a history of vegan and vegetarian cookbooks. Printed pages, of course, play a key role in disseminating information and it makes sense to use the cookbook as the lens to traverse these various eras. Books also have the benefit of a clear, time-stamped historical market, but if there is a criticism here, it is that Kennedy relies too heavily on the cookbooks. Nevertheless, Kennedy creates a strong sense of the timeline during which vegan cuisine has been adopted by moving chronologically through the publication of seminal works. Using the publications, she examines how they have impacted vegan, vegetarian, and omnivore food choices.

One great example of how cookbooks have a profound influence on culture is in how the concept of complementary proteins entered into the collective consciousness. A frequently repeated myth claims plant-based diets are unable to provide enough protein, and Kennedy traces this source to a single, popular book. The belief is based on the concept that plants alone cannot produce the correct protein and need to be consumed in combination with other foods–rice and beans, for instance, would provide the right combination of constituent components. But as Kennedy debunks it, this popular idea has roots in the 1971 publication of the first edition of Frances Moore Lappé’s Diet for a Small Planet. As a testament to its popularity, the myth persists today even among nonvegetarians, despite corrections in later editions. Kennedy illustrates how these narratives enter into the collective consciousness, stating that a “mistake has remained part of the conversation on whether a vegan or vegetarian diet can provide enough protein.” Narratives like this create the backbone of the book’s premise extending the value of the book beyond the vegan community.

Kennedy even examines various restaurants and their impact on different trends. Some of these restaurants are famous for their vegetarian menus, like Dirt Candy in New York City, which has a Michelin star. Most of these restaurants are located in places you might expect to find a vegan restaurant, like Brooklyn or San Francisco. Whether the absence of other locations is an oversight or simply an indication of the lack of restaurants in other parts of the country is unclear. It seems strange to think today, with the broad accessibility of vegan cuisine, that there was ever a time when going out to eat required a major metropolitan city. Surprisingly, the increasing popularity of veganism hasn’t always been great for vegan restaurants or trends. In New York City over the last two decades, a number of vegan restaurants specializing in recreations of items like cheeseburgers, fried chicken sandwiches, and cheesesteaks have started closing down in part because of a wider availability of vegan cuisine and similar items at nonvegan restaurants. Innovations like Impossible and Beyond Meat have mainstreamed veganism in a way that specialty shops no longer are necessary to serve the community. Even Champs Diner, which Kennedy cites as one place still dedicated to these creations, actually closed earlier this year (replaced with Ro’s Diner, a copycat and also vegan). But it raises a question: If vegan food is becoming mainstream, is there still room in the world for dedicated restaurants?

There are moments where Kenendy could have gone a bit deeper into some of the developments. For instance, when she brings up aquafaba, the thick juice from canned chickpeas, we are given only a brief mention of it as the “gooey liquid in a can of chickpeas that can whip up like egg whites, bind baked goods, and provide a white froth on shaken cocktails like a whiskey sour.” But there is a missing narrative here–where it came from, who discovered it, how it transitioned from that weird sticky stuff poured down the drain into the key ingredient for frothy egg-white filled cocktails. Details like these could have filled out more of the overall history of veganism.

The chapter on vegan dairy products is one of the best, in part because it is wildly accessible to readers in the sense that even omnivores in today’s world have likely sampled some of plant-based alternatives. Oat milk, soy milk, and rice milk are all readily available at national coffee chains and a popular option for the two-thirds of the population who is lactose intolerant. The evolution of vegan cheese, the substitutes, and claims that some are now indistinguishable in the context of pizza constitutes a fascinating reflection on the subject.

Kennedy provides a refreshing perspective, however briefly, regarding the importance of animals in the agricultural cycle as she acknowledges the impossibility of removing them entirely. Ardent eco-vegans might take issue with her ultimate conclusions that aspects of veganism are not entirely environmentally friendly. She doesn’t trace all the various foodways that are less environmentally friendly, but one that sticks out is how 97% cashews, a big part of the vegan dairy scene, are derived from sources that are not necessarily sustainable or ecologically friendly. More importantly, she reveals her own shift away from maintaining an entirely vegan diet.

No Meat Required serves up a well-researched look at American veganism and lays the groundwork for plant-based cuisine. Should civilization last long enough, she is the Pliny of meat-free foods.

NONFICTION

No Meat Required: The Cultural History & Culinary Future of Plant-Based Eating

By Alicia Kennedy

Beacon Press

Published August 15, 2023

[ad_2]

Source link