[ad_1]

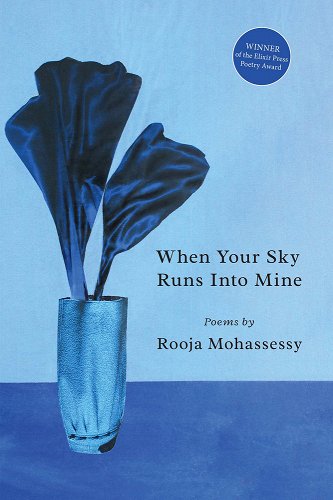

In September 2022 in Iran, Jina Mahsa Amini was arrested for wearing her hijab incorrectly; that is, the fabric did not cover her head completely. Three days later, she died while in police custody from severe head trauma, which the Iranian government denies. Her head, the object that caused her arrest, was beaten, the brain damaged beyond repair. Indignation swelled through Iran, women and girls flinging their chadors into the sky, demanding the right to choose whether or not to wear a headcovering. Hundreds of protestors, women and men, have been killed in protest or by executions by the Iranian government since. The legal right to choose whether or not to wear a headcovering has been on the Iranian mind for many years, and it may surprise some to hear that there was a time, during the 1930s, when the headcovering was banned in Iran. It may surprise some further to learn that there was a spell in modern Iranian history when women could choose—from 1941-1979. In all of these lived times, the headcovering has held power, this piece of cloth. In Rooja Mohassessy’s poetry collection, When Your Sky Runs Into Mine, winner of the Elixir Press 22nd Poetry Award, the power imbued in this piece of cloth is chronicled from the onset of the 1979 Iranian Revolution and from a personal perspective, through absorbing and erudite yet moving verse.

Though the chador holds a variety of meanings and purposes for women who have worn them in recent decades, the head-and-body coverings in Mohassessy’s collection represent a smothering of individual freedom. In “Hijab in Third Grade,” we see more than just a new school uniform; we see the acknowledgement of gender-shame:

In the mirror, buttoned up the midline

to the schoolgirl’s throat is midnight

falling darkly to her ankles, shunning

her shins.

The title of the poem—”Hijab in Third Grade”—carries its own solemn weight, that a little girl should be covered in fabric head-to-toe, if not to conceal her current shape, then to condition her for her womanhood. The schoolgirl is a bit older in “By Age Ten I Understood the Heft of Fabrics,” and her awareness of the stakes of her gender increases. In this poem, the perspective changes, too, from third-person to first-person, the fear moving closer to home, chiseling her innocence. Girls wearing navy overcoats, who have the privilege of raising their sleeved arms to allow breezes to reach their hidden skin, halt their chatting as they watch a black-chador-cocooned woman walk down the street:

If a man brushed past it hid one eye, both lips

at a crooked angle; we’d eat our words

midsentence and stare, our parents

jerking us away, worried we’d fall

into a harm worse than a manhole,

a wrong even they could not save us from.

Here we see another lived account, a highly specific visual narrative in verse, showing the reader that the heft of the garment goes well beyond the sweat in summer heat, beyond the inability to move the body unencumbered; the weight of the fabric brings life or death, and the decision-maker is the passing man, seemingly any man at all whose mere gesture, that of hiding an eye from the sight of a woman, is the point of power, so much so that that the girls are jerked away from this display, its influence causing irreparable harm.

Mohassessy logs some of these harms “worse than a manhole” through a wider lens in “Before and After the Revolution,” a poem in four verses contrasting the severe eighties to the looser fifties and sixties, and landing on the 2020s, when “…they [the Iranian government] still won’t trust us…” In the fifties, the tango and miniskirts are allowed; in the eighties, Coke bottles are inserted into the rectums of virgin girls for listening to the Dirty Dancing soundtrack, and the girls are arrested and raped repeatedly in jail for wearing lipstick. Mohassessy presents details of the extreme governance of the Iranian female body. One feels the control, the stoppage, the smothering of being. In “Death Was Like a Desire,” a poem in couplets, one line flows to the next, like the pressures of women, increasing still:

of new edicts. Fatwas condoned our arrest for the rouged

contours of our lips, not what came out of them, our hands,

the shade of polish on our nails, not who we’d caressed

the night past. In the cell we sat swathed in our last

layer of protection, prayed for lenience, for the whip

to thrash us over, not under our chadors. They said a bare square

inch of our calves, our song, called for repentance. And so

they defiled us at night since, they said, we were dirty already.

In this same poem, Mohassessy speaks for Iranian women and girls when she says, “We knew / no doubt we were undeserving—were taught / as much at school and for half a century prior.” If generation after generation, an entire nation is taught that their legal system is simply enacting the edicts of their god, then how do women (and men) fight such a system, even in their own minds? If they had the ability to speak their minds and hearts without repercussions, what would they even believe to say?

The Iranian woman of Mohassessy’s collection is not just muffled in Iran. “Interview for Asylum” begins with an officer in an unnamed country telling the interviewee, “Discarding your hijab is non-negotiable,” one directive of many in a poem demanding obedience to man and country:

Let us examine your profile. Please stand.

(scrutinizes her face closely)

In time, you’ll need to carve and discard the inordinate

chunks of your cheeks,

reject the ridges

of your congenital jaw.

(returns to his desk)

Now remember, blow jobs should be airy—

be sure to make room.

As for your blood, it’s thick. It extends too far back.

From country to country, from man to man, the asylum-seeker has landed. For survival, she obeys, a response she has mastered. Yet in this poem, she has no voice; she does not speak:

And your tongue. Utter a few words, would you?

Discordant. Do you hear it? Can it be tuned?

O so quiet! Terrified beyond despair. She’ll never serve.

Mohassessy’s Iranian woman, trained to be docile, is now not meeting the man-standard of verbal expression in a different country, and her life is in yet another man’s hands.

The Iranian immigrant girl of Mohassessy’s collection is muffled, too. When the teacher asks her to tell the class about herself in “All About Me,” she cannot speak; however, the narrator knows what to say. Here and in other poems in this collection, the perspective is fluid: “Oh my feline soul, / when he asked the child in the front row to tell / all about herself.” Who is speaking to whom? It is exciting to peel back the layers. There is the narrator; there is the soul; and there is the child. The narrator speaks to her own soul, which is the same soul of the child, yet the narrator views the child (the self) from a distance, observing—just as we do when we see our little selves in our memories, knowing now, as adults, the perfect words to say, if only we would have been brave enough to say them:

she would’ve spun in her Baluchi skirt stitched

with mirrors and demi-moons, to show

and tell, and the children would’ve reached for the shards

of light dancing on the walls, not shunned her like a castaway.

Muffled, also, in this collection, is the narrator’s mother—but only genetically. She cannot hear with her ears or speak with her mouth, yet see what this woman, “mute as a 1920s flower, deaf / as if by grace to the air raid sirens,” produces in “War”:

she greeted guests, looped through folding stools,

her gold hoops lost in her curls. Once a month she’d tuck

the good-sized deaf and dumb society of Tehran

into our three-bedroom flat she’d decked

into a close semblance of a French brothel.

This mother does not wither but listens to the needs of her community and provides strength in secret and creative ways. Mother’s strength is seen again in “Rose D’Ispahan,” where she is again compared to a flower, this time la rose du petit prince, a “pale ghost” to the robust flower she used to be. Yet with all the mother’s strength, we feel the narrator’s pain as she ruminates on what it must have been like for her strong flower who helped her daughter pack to leave Iran:

Mother, once your little prince left, how did you haggle

for rationed coupons? Who signed the air-raid siren

into your eyes? You managed though the house no longer heard

the doorbell, could barely read or write, every room dumb,

half-opened doors shutting without a sound.

Empathy for the hardworking woman culminates in “Godliness,” the only prose piece in the collection—lush and deliberate, like all the pieces here—where the narrator still does not say what she wants to say to the person before her, this time a middle-aged Chinese woman who pummels the narrator’s muscles and purifies her pores in a luxury spa in Shanghai. “O sister! I know your gait, the way you shift weight like a beast of burden, but they catch up with us, you see.” The narrator thinks these words and over two-hundred more words of compassion but instead says, “Xin Ku Le,” meaning (abbreviated), diligence, exhaustion and action completed. Again in this collection, unspoken thoughts.

This piece is nestled in the third section of this collection, one that contains a couple of heady poems of freedom in exile such seen in these lines in “Loneliness”:

I’ve been familiar with the men

of this land and their jet-black hair,

friendly with women, their thighs

parted in monsoon afternoons,

The air pressing, pregnant with downpour.

And these lines in “Bared”:

the waist, silky madronas peel before my eyes. I walk the dog, check on

toyon at the bend in the road. It came out in June, thick creamy clusters

quickly wilting like a bouquet in the musty hands of an anxious bride.

But Mohassessy does not escape her Iranian-woman yoke for long in this collection—on the contrary. The poems are anchored in Iranian history, beautifully wrought, and unfortunately, highly relevant as we are, today, witnesses to the harrowing fates of Iranian women if their hijabs should slip, and to Iranian men if they should stand up for them. When Your Sky Runs Into Mine is a personal and political record in rich verse, both in construction and content, that cannot and does not keep quiet.

POETRY

When Your Sky Runs Into Mine

By Rooja Mohassessy

Elixir Press

Published February 1, 2023

[ad_2]

Source link