[ad_1]

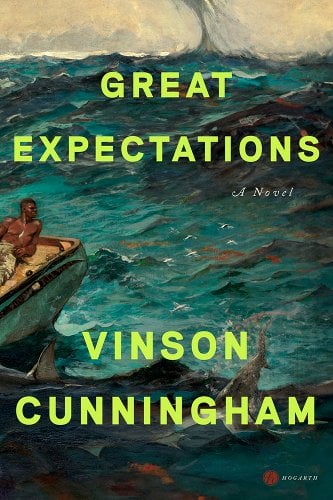

St. Augustine of Hippo tells us that if we understand something, it is not God. It does not follow that if we don’t understand something, it is God, but sometimes the whispering second notion appeals to an instinct, and we try to see the mysterious as the mystery of God, anything strange and new as His. Vinson Cunningham gets at this kind of tempted yearning in his debut novel, Great Expectations. His narrative, which we take to be told by a staffer on Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign though Obama is not named, takes as a guide the sense that something quasi-religious is going on: a great deal is expected of an upstart Illinois senator, so much that a pastor who normally avoids politics claims he will “usher in some new, unimaginable dispensation,” an age of miracles and signs and wonders. But the narrator, who has studied “the candidate” many times in the flesh, can finally “interpret the symbols he offered in profusion.” He knows all the rhetoric, and it doesn’t impress him anymore. He leaves the hotel near Grant Park where Obama will give the final speech of the campaign, seeks a childhood church, and, prompted by the example of a bona fide Black saint about whom he knows very little, he prays to the “veiled God” of his youth, who “still spoke words [he] couldn’t comprehend.” The American idol has thankfully been taken off the altar. If Cunningham has another novel in him he might well take on the idol of America—the right has its own heresy of Americanism to answer for.

David Hammond is a Black man in his early twenties, raised partly in Chicago and mostly New York. He has a daughter with a woman he is no longer seeing, and having dropped out of college in Vermont, he turns to private tutoring. His only student is the son of Beverly Whitlock, a longtime supporter of the Illinois senator’s career, who now brings him on to help with the presidential campaign. He works at a fundraising office in Manhattan, then is dispatched to New Hampshire for the primaries. There he meets Regina, a fellow campaigner with her own political ambitions. The campaign takes him to California, Connecticut, and back to New York. There are a couple developments that oughtn’t be discussed here, but every reader knows at least who wins. The novel is based on Cunningham’s own experience as an Obama staffer, and without knowing how fictional it has become in his hands, one can complain that it feels shapeless. Some personal crisis might have been devised and put into hectic motion alongside the race, the kind of thing that feels trumped up in a memoir but can be accepted as a protocol in a work of fiction. As it is, David has time to take us back into memories of childhood high jinks in Chicago, or of Pentecostal church in New York, and these excursions become more frequent in the later parts III and IV. There are a couple longueurs: a scene at a New Hampshire bar, and a discussion of old photographs. If the title raises up one great expectation besides those placed in the candidate, it is of some Victorian coincidence, or reversal of fortune. There is a twist connecting the two novels, but plot twists don’t do as much for us when the narration is as ambivalent and apologetic as David’s.

Cunningham is a theatre critic at The New Yorker, and is not coincidentally very interested in speech and movement. David notes the Black church cadences in the senator’s voice and the gestures that accompany them. The campaign events, public theatre for which David has behind-the-scenes access, are the strongest scenes, marked by moments like Cornel West’s introductory bow that “ended with his torso perfectly parallel to the ground.” But when David’s on the move, he looks hard, doesn’t see quite enough, and reaches for something that isn’t really there, like the “profligate branches of dead sumac at the sides of the road,” or the “thin, digressive trunks of the palm trees.” Readers might be disconcerted when Regina is reported to have “verdant eyebrows” and disappointed when David calls even the candidate’s body language “sour” before calling his features “sour” three pages later.

Cunningham writes fairly well, but he relies too reliably on em dashes—he doesn’t always finish and return right away; he often has a semicolon in there too—to bring elaborations and side notes into something like order. And excessive elaboration is something of a problem throughout. The same instinct for commentary that calls branches “profligate” and tree trunks “digressive” is greeted with a photograph of Beverly, David’s confidante and guide, and sees in her smile “a sociology of merited satisfaction.” Cunningham has accidentally demonstrated Great Expectations’ other stylistic issue, its tendency towards oddly detached, pseudo-professorial interpretation. It is not so much that sometimes a cigar is just a cigar—Mr. Clinton’s cigar seems to have been a symbol before it was a substitute—but a novelist who can’t let a smile just be a smile for a minute, so eager is he to transform it into some insight, is in trouble. David gets to Regina’s apartment, and gives a perfectly good account of dubious, dank smells, a “low corduroy couch,” dull razors and “exhausted” toothbrushes, but only so that he can tell us how such messy homes “disclose something fundamentally earnest, well-intentioned, serenely industrious, and refreshingly self-accepting about the characters of the people who live in them.” We’re off in an abstract zone of types, with a few lost metaphors (“disclose,” “fundamentally,” “refreshingly”) sounding echoes of the brick-and-mortar world David and Regina actually live in, and Cunningham’s readers don’t need any of this, anyway. Does Pip have to explain to us after our first look at Miss Havisham’s drawing room that she’s clinically barmy? If you can understand it so quickly and thoroughly, it is certainly not God, and it isn’t even anything very interesting. And without that kind of interest, you need a real plot, an irony or two, a few laughs, anything at all to keep things lively.

FICTION

Great Expectations

By Vinson Cunningham

Hogarth Press

Published March 12, 2024

[ad_2]

Source link