[ad_1]

Rare are books that can truly – in the most genuine and interesting sense – be called experimental, but Alexandrian poet and writer Noor Naga’s first prose novel is one such rarity. Sharp, switched-on, and self-interrogating, If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English masterfully continues, long after the last page is read, to provoke uncomfortable yet essential questions about what we demand from literature that represents otherness.

The experiment in Naga’s novel is primarily one of structure and perspective. There are three parts. The first, and longest, details the arc of a doomed Cairo romance between an unnamed Egyptian-American woman arrived from New York in search of a homeland she’s never known, and an unnamed poor Egyptian man who has left behind a traumatic past in the small village of Shobrakheit. It is 2017, six years after the Arab Spring, and the dream of “birthing a new order” in Egypt has faded away. “‘At some point after the Rabaa massacre of 2013,’” the boy from Shobrakheit (as he is known throughout the story) declares, “‘after the sugar crisis and the floating of the Egyptian pound last November, after it became clear that all the men who had disappeared from their beds at night for tweeting were not going to be released, the unthinkable happened: people began to long for the days of Hosni Mubarak.’”

This first part of the novel is told in short, single-paragraph chapters, each beginning with a riddle-like question (“If a city is actively trying to kill you, should you take it personally?”), and alternating between the perspectives of the two characters as they meet, get to know each other, become intimate, live together in increasing isolation, and eventually come violently apart. Permitting the characters to narrate in tandem from their separate points of view allows Naga to gradually reveal their divergent identities, backstories, and preoccupations, giving us valuable insight into the evolution and destruction of their relationship as it is understood by two people from very different worlds. And as the first part of the novel comes to a close, it’s painfully evident that the circumstances of their birth, the barrier of language, the startling inequity of their privilege, and the resulting guilt, resentment, and abuse make impossible a lasting connection: “I find myself measuring for the first time how far America is from Cairo, let alone Shobrakheit. How to bridge this ocean?”

The second part of the novel details the aftermath of the couple’s breakup. Relieved to be released from the burden of the relationship, the Egyptian-American woman returns to speaking in her native language and to what is familiar: “For too long I have been that other girl: weak, self-effacing – an obvious American in her fat-tongued, blubbering Arabic, and punished for it. But not anymore.” Falling easily back into her class privilege (though not without an uncomfortable awareness of it), she begins to date and sleep with William, a white British man. She continues to live in her large, light-filled apartment with multiple balconies, and teach English at the British Council in Cairo. The boy from Shobrakheit, meanwhile, stalks her movements from a distance, the grief of his loss adding fuel to his long-standing cocaine addiction. After enacting a desperate and devious plan that brings him back into her orbit, tragedy borne of jealousy befalls the boy from Shobrakheit, and abruptly ends the novel’s action.

The short chapters with alternating perspectives continue in this part of the story, but gone are the riddles; now introduced are footnotes, or “stage whispers,” to define certain expressions or references supposedly specific to Cairene or Egyptian culture, ones that were previously left undefined in part one of the novel. These footnotes, however, are mostly inaccurate, even ridiculous (“Despite their efforts to blend in, government informers in Egypt are always recognizable by their state-mandated painter’s mustaches”), and begin to suggest (if the riddles hadn’t already) that a game of sorts is afoot, one designed perhaps to poke fun at and, on a more critical note, illustrate the limits of an oblivious Western reader’s ability or willingness to understand a Middle Eastern culture beyond exotic stereotypes and fetishistic descriptions.

The third and final part of If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English – structured as a play script complete with stage directions – takes a fascinatingly metafictional turn, revealing Naga’s master plan to interrogate the very narrative she has so carefully created. The story of the Egyptian-American woman and the boy from Shobrakheit is now being workshopped as a memoir (don’t we always assume a first novel is autobiographical?) in a creative writing class populated by an English-speaking instructor and seven students, including the memoir’s author, Noor. She has brought for critique the intended third part of her manuscript detailing the complicated aftermath of her final encounter with the boy from Shobrakheit. Her effort, however, to provide a nuanced portrayal of the unjust circumstances surrounding this final encounter, rife with cultural and class implications, is met with disapproval from all but one of her classmates, most of whom are quick to condemn and dismiss the boy from Shobrakheit as a “junkie” and “psychotic stalker-rapist,” deserving of his fate. Their conclusion is “we do not need the third part.” “‘It is not about Cairo,’” one of them declares, “‘it is a deadly romance.’”

Except that the story is entirely about Cairo, and by concluding the novel with the privileging of the voices of a group of presumptuous, nescient readers (most of whom cannot even properly pronounce Shobrakheit) more interested in emotional investment in the characters and sensory descriptions of “the textures and kinks that make Cairo Cairo” than in wrestling with more uncomfortable truths about power, class, and intent, Naga ridicules our ignorant expectations of “marketable” literature depicting otherness. As a writer, Naga does not excuse herself from this scrutiny, the final revelation of this inventive and brilliant book scathingly proving her very point.

FICTION

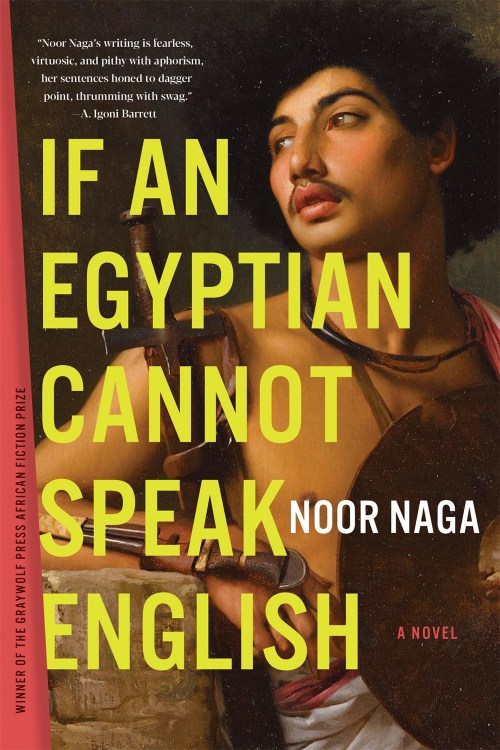

If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English

By Noor Naga

Graywolf Press

Published April 12, 2022

[ad_2]

Source link