[ad_1]

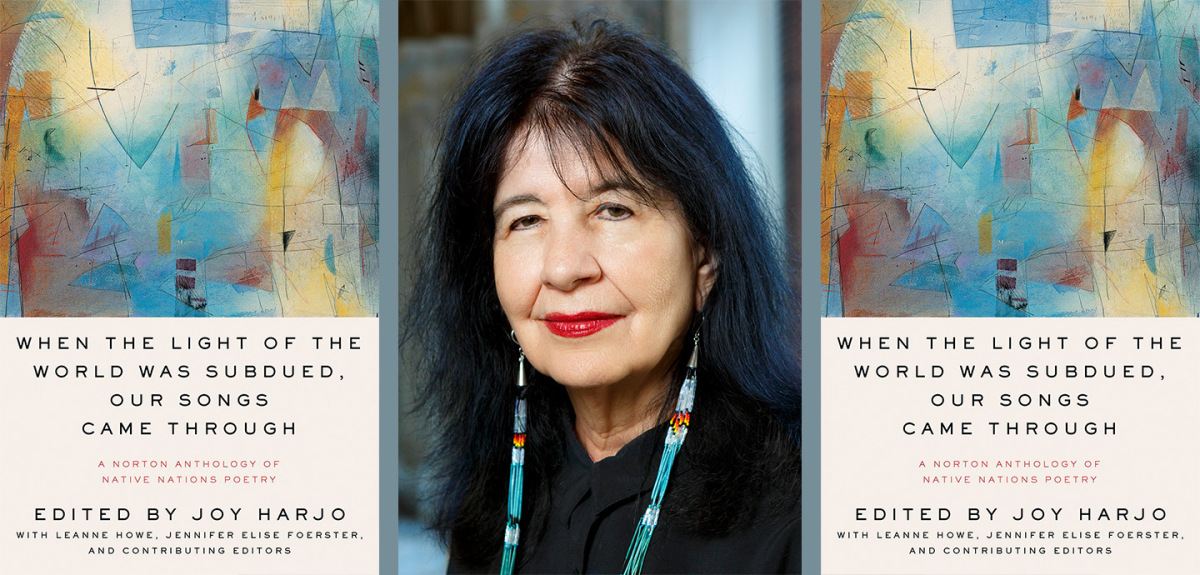

“It is poetry that holds the songs of becoming, of change, of dreaming, and it is poetry we turn to when we travel those places of transformation, like birth, coming of age, marriage, accomplishments, and death. We sing our children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren: our human experience in time, into and through existence.” So begins the anthology When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through, the first comprehensive anthology of Native Poetry, edited by Poet Laureate Joy Harjo.

Included within this landmark anthology are hundreds of poems dating from the 17th century to the present, representing close to 600 Indigenous tribal nations in the United States mainland, Alaska, and the Pacific Island territories. The anthology’s historical and geographic arcs celebrate Indigenous poetry in all its forms—oratory, song, ritual—and bring together the lived and diverse histories of our nation’s first peoples.

I recently talked with Joy Harjo about her experience assembling this anthology, her hopes for the image of Indigenous poetry, and the value of poetry in the present.

Clancey D’Isa

This collection includes over 160 Indigenous poets, dating from the present back to the 17th century. It includes both written works and poems which have been traditionally delivered orally. Could you tell me a little bit more about the structure of the anthology?

Joy Harjo

The thought behind the structure of the anthology was to divide it by geographical areas, instead of by state. It would be difficult to divide it by tribal groups because we only originally were offered 300 pages for such an anthology. Even with the amount of pages we have now, a little over 400, the question still persists: how do you fit over 500 federally-recognized tribal Nation’s poetry into an anthology that size? That was the first challenge.

Then you have to decide, of course, how are we going to do this: will it be chronological by age? It was really important for us to make a point that our tribal nations are situated in very specific geographical environments, in specific geographical areas, with particular environments. Many of the pieces are located specifically in those places. Traditionally pieces belong to certain areas, in that they wouldn’t have come into being without being in certain areas. We decided to divide the anthology into five rough and inexact—nothing could be perfect—geographic areas. For the Muscogee peoples, our directions go East, North, West, South, and back around. We decided to let the Northeast and Midwest go first, and then we would come back around to the Southeast.

When you read the sections, you can also see and come to understand a certain sense of place. If you read a section from beginning to end, you can read how colonization moved in different ways.

Clancey D’Isa

The anthology’s structure supports a beautiful reading experience. Throughout the anthology, there are biographies of each poet before their poems. Could you tell me more about how you imagined those biographies informing the reader?

Joy Harjo

It is always important to give context in the midst of such a project. This is such a wide-ranging book of poetry, in terms of time, in terms of tribal nations represented, in terms of generations included. We felt that it was very important to preface each poem or section of poems with a little biographical statement, so that it would give at least a little bit of context to the poems which followed. Through reading, you may move from one tribal group to another, and the distinctions and histories are important. For instance, the Pacific Northwest, Hawaii, and Alaska those areas cover miles and miles and miles. Each of those areas could have its own anthology. We could do a whole series—an Encyclopedia of Indigenous Poetry—because so much was left. We had to work within page parameters and there were many poets who were not included. We could have easily doubled the anthology.

Clancey D’Isa

You talked about the way you could track the movement of colonization through these poems. These poems trace many other things too: Indigenous traditions, blood politics, climate change, the genocide of Indigenous people, identity politics, and generational hope. As an editor, how did you approach such an expansive and historically significant project?

Joy Harjo

What makes this project unusual is that we decided that the panel of experts would consist solely of Native Poets. We had Assistant Editors who were students at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, where I was teaching at the time. I had two different classes who assisted with the basics of putting the anthology together. They got to be part of the process alongside the Native Poet Editors. We convened on Skype, in a time before Zoom, to discuss what would be included in the anthology.

There was a great joy, in all of us, in reading poetry. The opportunity to, one, see what was there and, two, to read, was a wonderful process. The email exchanges were also insightful and useful as we moved collectively through the editing process. I especially appreciated learning specifics of construction and meaning that were rooted in languages, and of experiences particular to geographies and tribal histories.

The last part of the process of editing was when the three editors—Leanne Howe, Jennifer Forrester, and I—decided to read aloud as part of the process for final editing before we sent the manuscript to Norton. To hear the introductions and poetry aloud was so powerful. Hearing edits and the final work are an important part of my revision process for all of my projects. That’s how I hear what I miss from seeing the writing on the page. It took us several hours to read the whole anthology. Often we were in tears, sometimes we laughed. Overall we were inspired at what our peoples had accomplished in their lives and in their poetry. We want people to see that we are human beings. We survived beyond the cavalry coming after us in the movies; we aren’t all Pocahontas; we are human beings and there is a range of experience and emotions in our lives. All kinds of experiences mirror this in this collection.

Clancey D’Isa

Your introduction sings of an American Poetry that, at its core, recognizes Indigenous Poetry. As you note there too, there cannot be an American poetry without Indigenous poets. What does this anthology do to further redefine the relationship between American Poetry and Indigenous Poetry?

Joy Harjo

There has never been a comprehensive anthology of Native Poetry. Some years ago, I edited a Norton anthology of contemporary Native Women Poets, but there has never been a comprehensive anthology of Native Poetry. That says: one, that there hadn’t been, with any of the major presses any such essential text; two, that there was a need for it. We do not see Native peoples represented in the American story usually except as primitives, those who were in the way of progress. We are not present in the American literary canon, rarely on the prize lists. Our stories of racial and cultural violence have been excluded from the urgent larger narrative in which we are currently engaged. We have been disappeared.

This Anthology reframes American Poetry to include Indigenous Poetry as necessary to American Poetry. The act of the book appearing, being present with over 400 pages of poetry that go back from time immemorial to the present does that work. We are poets, we have accomplished poets, and we had poets long before there was an entity called America. We were here, we are here, we didn’t disappear or die; but, we are living voices and we are poets.

We’re crucial to the American story. There would be no America without Indigenous peoples. You cannot tell a story, whether it’s the story of American poetry or the story of American history or the story of American anything without the the contributions and presence of Indigenous peoples

Clancey D’Isa

How can poetry help us now?

Joy Harjo

Poetry holds a crucial role in society. Poetry can hold, in a very small container sometimes, what nothing else can hold. Poetry can hold grief so immense that there’s nothing else [that] can contain it; poetry can hold stories that are dense or unspeakable; poetry can hold joy and awe; poetry can hold the contradictory parts of ourselves, the contradictory parts of the country. Sometimes three or four little lines can hold a whole lifetime.

We can speak out in poetry in a way that allows people to hear multi-dimensionally. A poem can be constructed of many dimensions. Therein is the gift of metaphor. Collectively the arts are like that; but, poetry, because we’re humans and we speak, has that power. I’ve often wondered what role humans have on Earth—because there’s nothing that we appear to do that seems to regenerate the Earth. The only thing I can come up with is that we’re the story gatherers and the song makers. That’s our contribution.

Clancey D’Isa

What is your hope for this Anthology?

Joy Harjo

This Anthology, as comprehensive as it is, just barely touches on the wealth of Indigenous Poetry that exists. It is a thin slice of who we are. There are many, many, many more poets and many poets we couldn’t include. I hope this Anthology inspires people to listen, and that Native Poetry and Native Poets become included in the ongoing story of who we are as a nation and society of many.

Anthology

When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through

Edited by Joy Harjo, with Leanne Howe, Jennifer Elise Foerster, and contributing editors

W. W. Norton and Company

Published August 25th, 2020

[ad_2]

Source link