[ad_1]

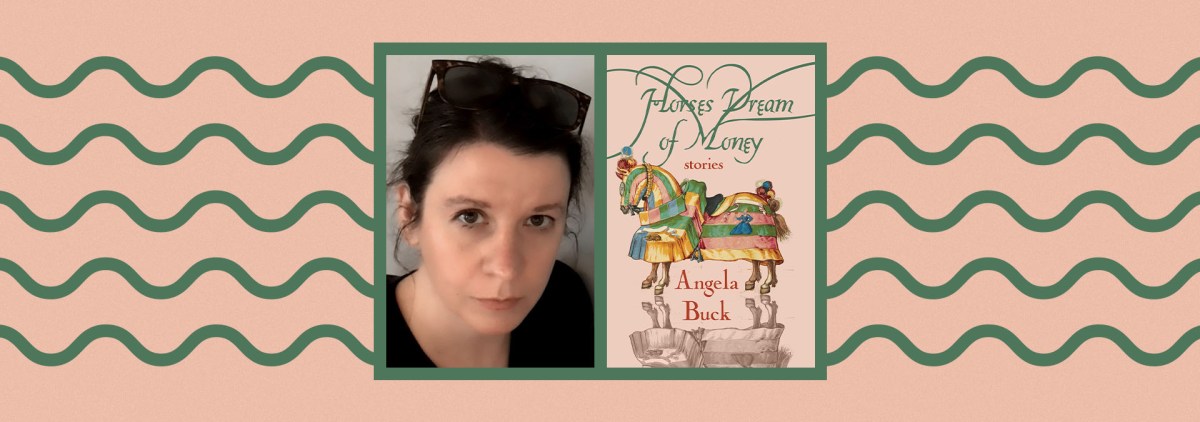

I have known Angela Buck for sometime. We went to graduate school together at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, where I knew her to be funny, thoughtful, and incredibly talented. Her new story collection, Horses Dream of Money, exemplifies all of those qualities.

The collection blurs horror and humor, fantasy and realism. It highlights the complexity of growing up in a world full of absurdities, while brimming with playful imagery and language. I spoke to Angela about what inspired this collection, as well as her processes for writing and organizing it.

Amy Brady

Your collection blurs the genres of realism, horror, and fantasy. Has this always been your writerly approach? Or is genre-crossing unique to this collection?

Angela Buck

I tried to write poetry before writing fiction. I say “tried” because I could never get the hang of line breaks. I’m a sentence writer ultimately with a poet’s attention (I like to flatter myself) to language. Language is an odd artistic medium because we mostly use it in a functional manner just to get on in the world. Also it’s tied to our bodies in a way that makes us think it’s ours. But the writers I like best treat it as an alien substance or at least something that isn’t easily pressed into the service of representation. In my limited explorations, I’ve reached the conclusion that language is an abstraction, not a representation of the world as such. Words select and arrange from the world’s surplus of matter and sensation, and necessarily leave things out. And sometimes a little cabal will try and fail to secede from the world entirely. So realism is a nice idea but bound to fail, and is probably only interesting in its failures anyway. Horror is an appealing genre to me probably because I feel fearful and paranoid a lot of the time, so it speaks to me on that level. If something supernatural or fantastic needs to happen in a story I’m writing, I usually indulge that desire, as long as it doesn’t involve elves or hobbits.

Amy Brady

One of the collection’s most provocative stories is “The Solicitor.” Please tell me about its origins. Was it inspired by real events?

Angela Buck

This story was inspired by feelings of disgust toward liberal feminism and its lame dreams of the girl boss. I tried to lean into that revenge joke and take it as far as I could by having a middle-class, teenage girl mail-order an older boy to serve as her sexual mentor and bring out her true professionalism. This is not really her choice but, instead, encouraged by her mother who wants her to be successful in life. Like the stuff we order on Amazon, the older boy is living under cruel and inhumane working conditions, a kind of wage slave. But then she falls in love with him! Which makes her no longer a professional but a person/comrade. So it’s kind of cheesy that way, but I felt happy when I was writing it.

Amy Brady

Your stories span eons. How does your writing process change when you’re setting a story far into the future versus the present?

Angela Buck

I don’t think it does. I follow my ear more than any definite plot or concept. The concept comes into view as I’m writing, never before. The exception in the book is “Coffin-Testament,” which started out as a style exercise. I wanted to write something that sounded like Sir Thomas Browne’s Urn-Burial. And then it took on a life of its own as a sci-fi story narrated by a group of lady-robots from the future trying to figure out American culture based on its trashy human remains.

Amy Brady

Despite their occasionally dark subject matter, your stories are often quite funny. How did you find your voice on the page? Especially such a distinctive voice that can traverse so many different tones and emotions?

Angela Buck

I experience life as something horrifying and absurd and ultimately beyond comprehension so that aesthetic combo comes naturally to me. I’ve felt that way for as long as I can remember but must hide it socially in order to convince other people that I’m a reasonable, fun-loving person. Look how relaxed I am! etc. Artistically, I don’t think moderation or responsibility is the answer to our predicament but instead to exaggerate the insanity of our lives and give into our most ludicrous visions on the page, where at least they can’t hurt anyone else. The writing I like best and try to emulate, I guess, is the kind that seems like it might break down or explode at any moment because of its awkward and volatile blend of emotions. Writing that is straightforwardly sad or uplifting or clear in its “this is how you should feel about this” attitude usually doesn’t appeal to me.

Amy Brady

The organization of stories seems to me to be an invisible but very important aspect of a collection. Would you discuss your process here? How did you decide the order of your stories?

Angela Buck

I originally wanted to call the book Masters and Servants, but the FC2 Editorial Board didn’t think that captured the playfulness of the writing, so I changed it to Horses Dream of Money, which is a line that comes from the longest story in the book, “Bisquit.” But all of the stories have to do with power dynamics in some way, the messiness of that, its subjective dimension. This is not to say that power is entirely a subjective affair, but political theorists and historians are better equipped to model its objective dimensions. Artists do the subjective part; that’s the division of labor. And I think as individual subjects we are kind of fucked—that’s my pessimistic point-of-view—and only rarely do we glimpse freedom, and when we do, we mistake it for something else or pretend not to see it because there’s nothing to be done about it (as an individual). And that realization is too painful to bear. I’m a conservative or a naturalist writer, I guess, to the extent that I believe we are almost entirely determined by social forces beyond our control. That’s why I feature many animals and children and K. and Molloy-like characters in my stories. That just feels more honest to me. So I began the book with “Work,” which is a short and concise poetics of doom and ended with “Bisquit,” which is the longest story and the most elaborate version of that theme. The other stories are like steps from “Work” to “Bisquit,” but don’t have to be read in any particular order.

Amy Brady

What’s next for you?

Angela Buck

I have several “projects” in stages of agony and disrepair. One is a self-help guide called Zombies, Do Less. Another is a coming-of-age story set in an alternate Florida-like locale which currently contains too many badly written sex scenes featuring teenage girls. Before I die I would like to translate Ovid’s Metamorphoses. When any of this makes its way into print, I will advertise it on my website.

FICTION

Horses Dream of Money

By Angela Buck

Fiction Collective 2

Published February 23, 2021

[ad_2]

Source link