[ad_1]

In the first chapter of her memoir, Acceptance, Emi Nietfeld reconnects with her estranged mother. Nietfeld, a young software engineer living in New York City, is about to get married, and her mother’s arrival to meet the new in-laws threatens the tenuously peaceful life Nietfeld has built for herself. Her mother, a former crime-scene photographer, is a hoarder, a bright but chaotic woman whose inability to wrangle her own inadequacies led Nietfeld to psychiatric hospitalizations, foster care, and a homeless stint when she slept in her car. As the book opens, Nietfeld is in a good place, now Ivy League-educated and employed in big tech, about to marry into a stable and loving family. While her tenderness toward her charming and cheerful mother is clear, so is her concern: will she upend this hard-earned peace?

The reader quickly realizes this is a flash-forward, meant to give us a cautiously optimistic end point, as the story then takes us on a harrowing ride through Nietfeld’s youth. Nietfeld is ten when her father checks out. Her mother is plucky and warm, arguably Nietfeld’s biggest fan, but incapable of making the sacrifices necessary to parent. This ineptitude provides the framework for the story; it is the catalyst for everything that follows. When the young Nietfeld protests the state of their home, which towering piles of dollar-store purchases and the stench of mouse urine and dog excrements have rendered uninhabitable, her mother blames Nietfeld for being difficult, convincing doctors her daughter is the problem.

Soon the young Nietfeld develops the only coping skills that make a dent in her misery and curb her powerlessness: bulimia, self-harm, and a suicide attempt. In the psych ward, she luxuriates in the cleanliness, hot water, and regular meals. Back at home, her mother seems as ensconced in her denial as before, and Nietfeld develops asthma and migraines from the mice and mold. When doctors tell her mother to clean up her act, she takes her daughter out of their care, looking for providers who will support her viewpoint and instead focus their energy on Nietfeld, who then resumes her self-destruction. Once put on heavy medication and saddled with a punitive medical record, Nietfeld becomes an unreliable narrator in her own self-advocacy, her agency stifled by the systems meant to protect her.

Acceptance shines emotionally when it points out the deficiencies in our social safety and healthcare systems and their effect on a powerless minor. Social workers don’t push to come inside the hoarding home because once they do, they will have no choice but to take action, knowing the child will be forced into a system where they might fare worse than with their neglectful parent. Treatment staff tighten the reins without mercy on teens desperate to be heard, putting the onus on them to accept their suffering and redirect their path with willpower, presumably because staff don’t have the resources to do so. From psychiatric hospitals to foster homes, from therapist visits to counselors’ offices, Nietfeld is encouraged to be resilient, admonished to take responsibility for her fate, told to show grit. “Kids too young to speak would be held responsible for their own problems,” she writes. “It didn’t matter how they were wronged, or how preventable the harm; their job was to contain the damage, making the blast zone smaller by absorbing all the impact.” From shelters to libraries, again and again she encounters adults who adhere to rules devoid of nuance and kindness.

Nietfeld’s memoir is a sharp critique of our society’s beloved narratives of resilience and meritocracy. Should a child have to pull themselves up by their bootstraps? Nietfeld’s tale demands empathy from readers for the girl who receives none from either culture or infrastructure. She brings us poignantly into the viewpoint of a youth whose sharp eyes discern the problem but whose voice is repeatedly unheard or—worse—turned against her. In the United States, children have little to no rights, no matter if their perspective might allow them to assess the situation more shrewdly than adults on the outside can. When the parent spins a delusional or harmful narrative, the child frequently has no recourse to rectify it and save themselves. But they shouldn’t have to if the system proved adequate in halting their fall.

Nietfeld is both forgiving and pragmatic toward her mother. The author seems clear that some of her traumatic experiences are the result of her mother’s inability to accept reality and fulfill the inherent requirements of caring for her offspring. “I knew she loved me with her whole heart and that love wasn’t enough,” she writes. What happens to a child whose parent claims to adore them but whose actions demonstrate neither the altruistic responsibility nor the self-care required? Nietfeld loves her mother too much to drill into accusations. Instead she lets the reader connect the dots, laying out plenty of heart-wrenching evidence on the page. Meanwhile she shows how she herself did the hard work of self-questioning and adapting: “For my parents, emotions created their own reality. It was up to me, as their child, to assimilate their points of view, even when they contradicted what I considered facts.”

Several mother figures step in to guide young Nietfeld through the years: the candid psychiatrist, the strict Christian foster care mother, the encouraging photography teacher, the mentor who provides both guidance and rescue at the worst of times, the college admissions consultant who pushes Nietfeld to strategize her Ivy League application process, and various friends’ mothers. Each of them helps to shape Nietfeld morally, emotionally, and academically—although perhaps not always in the way they intend. And while Nietfeld recognizes their valuable contributions, each of them leaves the young woman longing for more. None are her real mother after all; none provide that unconditional acceptance we expect to take for granted as children. And there lies the gripping hook of Nietfeld’s story: the despair of the unmothered child, inherently deserving of devotion but untethered from it and reeling.

Acceptance’s narrative arc follows Nietfeld as she struggles to wrap her brain around this existential injustice, as does the reader, while life continues to throw her horrendous curve balls. This is a propulsive memoir, written with the craft and fire of a page-turning thriller. And this makes sense: writing, after all, is what saves Nietfeld. Writing is how she learns to assert her own narrative and compel others to pay attention. “It seemed clear no one cared about my experience when I just said it,” she writes. “But if I could write well enough, I could trick a reader into caring.” Starting in exchanges with medical staff and continuing with Ivy-league college admissions which she saw as her only way out of destitution, Nietfeld hones her narrative. However, in rejecting her self-erasure, she must also manifest the self-sufficiency and fortitude she so fiercely wants to rebuke. Reality doesn’t give her a choice. “My past would be the price of my future, but only after it devastated me.” Embracing the system is her exit ticket, and writing is her vehicle. Acceptance becomes a tale of resilience and grit, and simultaneously a searing rejection of the cultural hunger for this narrative.

By bookending her memoir with scenes in the present, Nietfeld sets up Acceptance as a sort of love story between mother and daughter, two humans inherently connected through blood and affection but living disparate realities. When love stories end, there is heartbreak, and hopefully there is growth. To survive, Nietfeld must mother herself, taking on the burden and the pain that should be shouldered by her parent, but she must also mother that parent, repeatedly leading the way with wide-open eyes and demanding her mother face the truth. In light of Nietfeld’s harrowing journey, we come to understand their eventual estrangement as neither angry nor reactive, but simply the natural next step for a mother and child who never inhabited their respective roles. Sometimes love isn’t enough.

NONFICTION

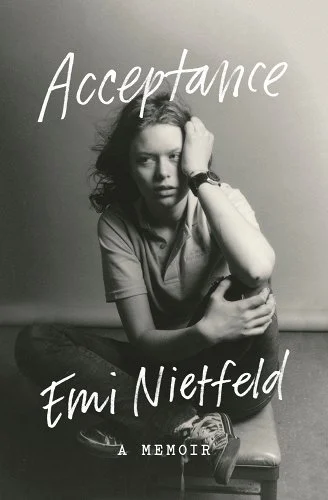

Acceptance

By Emi Nietfeld

Penguin Press

Published August 2, 2023

[ad_2]

Source link