[ad_1]

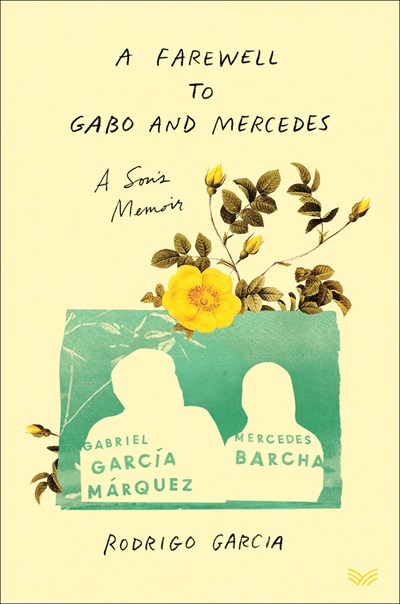

Rodrigo García lost his mother, Mercedes Barcha Pardo, in August of 2020. Like so many others, he was kept from her bedside by COVID-19 travel restrictions. In A Farewell to Gabo and Mercedes: A Son’s Memoir, he writes:

“Unable to travel, I saw her alive for the last time on the cracked screen of my phone, and again five minutes later, gone forever. Two brief live videos, separated by eternity, from which my capacity for storytelling has yet to recuperate.”

While García may not yet be able to communicate the experience of her recent death, her profound influence on his life and her shared loss of García’s father, writer Gabriel García Márquez, form the basis for this short but powerful memoir.

An award-winning director and screenwriter, García brings both his gifts as a writer and his filmmaker’s eye to the story of his parents’ lives and deaths. He frequently frames his experiences in images, calling a view of his father’s body in the mortuary “the most impenetrable image of my life.”

These images are woven into short, even fragmentary chapters: restless, uneven beats of memories, anecdotes, and recollections, flashes of wry humor, and eddies of disbelief and sorrow. Not a stream of consciousness—not nonsensical or disjointed—but the logic of grief reflected in a Morse code of spare and thoughtful prose.

Though García’s mother recently passed, his father died in 2014. Nevertheless, this account of his loss is as close as a breath on your cheek, its sharp detail and emotional immediacy all but erasing the years that have elapsed.

The passing of a literary icon is in some ways predictable. Gabriel García Márquez’s extraordinary body of matchless work, his Nobel Prize in Literature, and the profound love and devotion he inspired in his millions of readers guaranteed long before it happened that the news of his passing would be nearly as momentous as his extraordinary life.

García captures this singular aspect of his father’s death in a quiet stream of revelations. Floods of condolences began to pour in just after the news broke on social media. Documentaries on García Márquez’s life and achievements began to play on television even before his body was removed from the family home. Two hundred people gathered to grieve in the street outside his house, their numbers dwarfed by the thousands upon thousands that waited in line to pay their respects at his memorial at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City.

But this is not the story of a celebrity death. Instead, García manages to balance the vast scope of the loss of the writer with the achingly intimate particulars of the death of a father, which, though they may differ in detail, are nevertheless recognizable to anyone who has lost a loved one.

García weaves the details of his own story into a constantly fluctuating chiaroscuro of the banal and the profound. The constant flights back and forth between his life in L.A. and the family home in Mexico City, and a quiet moment in the garden, marveling that “nothing betrays the fact that a person’s life is ending in an upstairs bedroom.” Ordering a hospital bed for in-home care, and seeing his father eventually laid out on it in a shroud, his jaw carefully bound. The orderly, lulling presence of nurses and charts and medication schedules, and the dizzying moments after the heart stops. The waiting and uncertainty, and the end and the certainty.

Bearing witness to these moments can be uncomfortable, and while he offers them to readers, García frequently reflects on the tension between the public and the private that his family has always had to negotiate, right up into the very pages that he writes. He also offers personal glimpses of his father in his earlier days that will delight even those readers already familiar with the writer’s biographies: how a copy of Thornton Wilder’s Ides of March had a long tenure on García Márquez’s nightstand, how he characterized Elton John as a “bolerista,” how his confidence in the quality of One Hundred Years of Solitude waxed and waned depending on the time of day, and how when García attempted to speak to his father while he was writing, it was like trying to speak to a man in a trance, the writer so focused that he was “lost in a labyrinth of narrative.”

Alongside these gems, he also gives heartbreaking insight into García Márquez’s struggle with dementia. García writes of its effects, “He eventually reread his books in his old age, and it was like reading them for the first time. ‘Where on earth did all this come from?’ he once asked me.” How many readers, breathless at the annihilating conclusion of the six-generation saga of the Buendía family in One Hundred Years of Solitude, asked themselves the same thing?

(And yet, García reveals, his father could have written two more generations of the family into the book, but decided against it.)

Though ties to the actual text of Gabriel García Márquez’s books are not numerous, the quotations of his work interspersed throughout the chapters remind readers not just of his extraordinary talent, which vibrates in every line, but also, García writes, that “like so many writers, [García Márquez was] obsessed with loss and with its greatest manifestation, death.”

He notes that his father “complained that one of the things he hated most about death was that it would be the only aspect of his life he would not be able to write about.” Not only has García successfully taken up this mantle for his father, but he also does full justice to other themes that serve as cornerstones in García Márquez’s work: a deep reverence for the power of narrative and a fascination with the mutability of time.

These connections underscore García’s testimony that “No director, writer, poet—no painting or song—has exerted much influence on me compared to my parents, my brother, my wife, my daughters.” The legacy of Gabo and Mercedes is evident both in this book and by this book, its pages describing the impact of their momentous lives and its presence demonstrating their son’s inherited, inescapable need to tell their stories.

NONFICTION

A Farewell to Gabo and Mercedes: A Son’s Memoir

by Rodrigo García

Harpervia

Published July 27, 2021

[ad_2]

Source link