[ad_1]

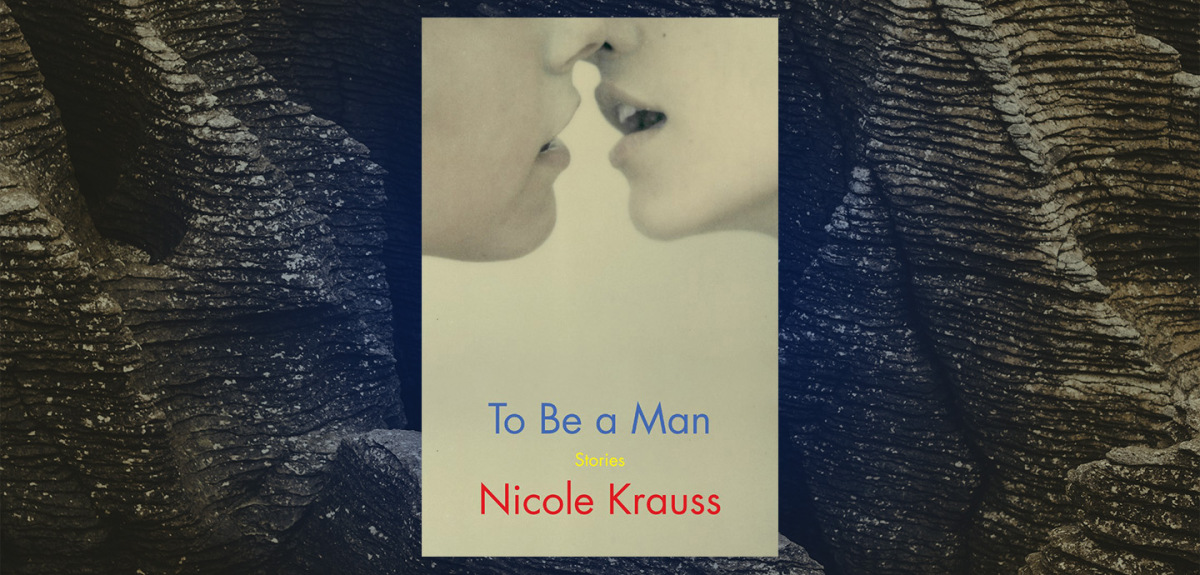

In the title story of Nicole Krauss’s fifth book and first collection of stories, To Be a Man, the narrative bends and breaks. Written in three sections with subsections, the narration shifts from first person to third, and then back to first. It’s only twenty-five pages. And it is as brilliant in execution as it is a pleasure to get lost in the stream of consciousness that creates the story itself. This kind of depth and structural experimentation is what makes To Be a Man such a beautiful, unique book.

Written with spare yet graceful prose, Krauss’s stories are intimate. They read like a secret between friends. There’s something otherworldly about Krauss’s work. I can’t quite put my finger on it, but there’s a sense of dreaming. The stories are realist in approach, certainly, but there’s a ruminating quality that reminds me of Patrick Modiano’s prose. They say there’s something awry here; the reality is rather unbelievable. Krauss’s creative framing, perspective, focus on love, sex, motherhood, and foreign lands are the common elements found throughout this extraordinary collection.

Several themes sew the book together, but the one that strikes me most is distance and its barriers. The stories are international, spanning New York, to Switzerland, to Latin America, to Tel Aviv, the grounding city in the collection. The push and pull between home and afar is an anxiety that adds necessary tension to Krauss’s subtle style.

In “The Husband,” a woman, Tamar, lives in New York, though she grew up in Tel Aviv, where her mother and brother live. When a man strangely shows up and claims to be her long-lost husband, Tamar’s mother takes him in even though he is not. Tamar is concerned, but being far away, she is powerless. This inability to act coupled with the worry that seeps into Tamar’s own psychology of repressed loneliness is what gives the story its meat.

In “I Am Asleep But My Heart is Awake,” a woman’s father dies in New York, where she lives, and she’s given the keys to his apartment in Tel Aviv. Here, Krauss taps into the strangeness of when we realize that our parents have lives apart from ours, their humanity. The Tel Aviv apartment represents a distance physically, but mostly emotionally.

The idea of the unknown is prominent in the book. Perhaps the best example is “Seeing Ershadi,” a bizarre, addictive story about an Israeli ballet dancer who possibly encounters a film actor (Ershadi) when she is on tour with her company in Japan. The movie itself captures the narrator’s interest, but it’s Ershadi who infects the narrator’s psyche. Why is he in Japan, and why must she find him so badly? Even she doesn’t know. When she recounts the story, her friend Romi claims to have had a similar experience with Ershadi. Krauss shifts into the third-person lens to tell the second half of the story as Romi, too, sees Ershadi. The hunt for the actor reads panicky, in a good way, and the whole thing’s strangeness gives an element of suspense. Everything about the story is foreign.

While the unknown haunts these stories, perhaps the most significant consideration for Krauss is the concept of love as a union. Divorce appears in almost every story, and often protagonists discuss the desire to never marry again. The story “End Days” is about Noa, a college-age girl whose parents are amicably getting divorced, and Noa must deliver the papers to the Rabbi. Neither parent seems to be very upset about the divorce, and this affable attitude troubles Noa. What is marriage for? In some ways, the ease of the divorce is what’s most troubling.

The idea of the independent woman is a firm stronghold in the stories, but also, the loss of companionship, too. Are children enough? Companionship comes in many forms. In “In the Garden,” the union is between an assistant and a landscape architect; in “The Husband,” it’s Tamar’s mother and her stranger lover, but it’s at the expense of Tamar and her mother’s union. In “Switzerland,” at a boarding house in Geneva a young teen girl has an affair with an adult man when he comes to town, and there’s a danger that looms around that relationship. Still the young narrator has a sense of longing for that secret pairing.

Krauss’s characters dig and rake at the debris of their lives, searching for something, looking into daily activities for meaning. In “To Be a Man,” the narrator considers stories people had been telling her: “She was not aware of having asked for these intimate and staggering stories about their lives, but maybe in her way she had been; maybe she had the look of someone who was trying to work something out, something at once vast and fleeting, which could never be approached head-on but only anecdotally.”

FICTION

To Be a Man

By Nicole Krauss

Harper

Published November 3, 2020

[ad_2]

Source link