[ad_1]

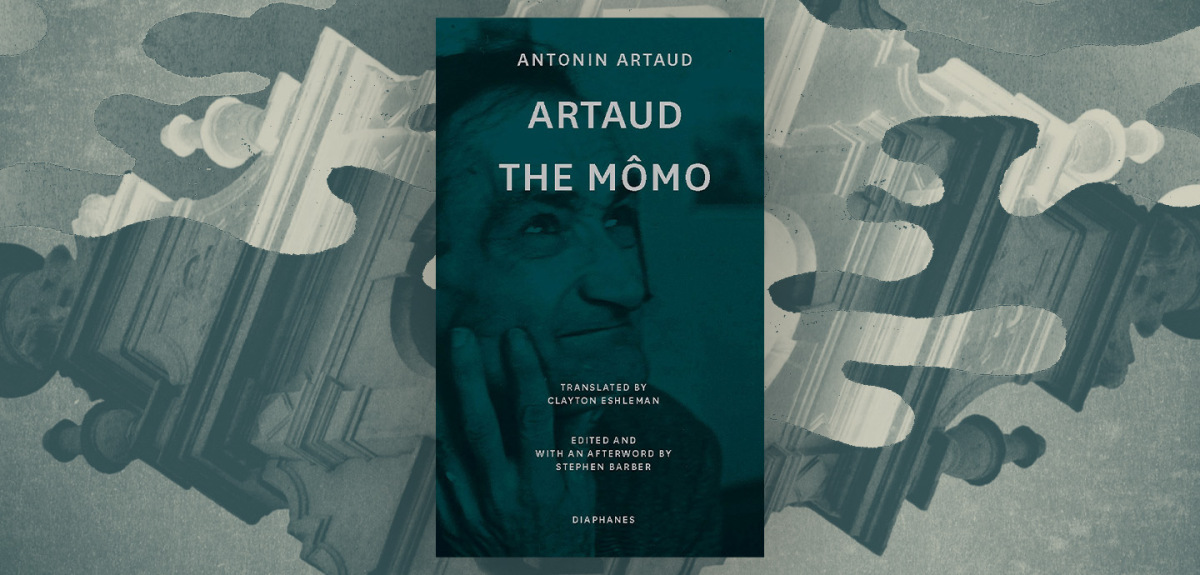

Antonin Artaud was one of the foundational voices in establishing the modern avant garde. His famous writings on The Theater and Its Double, and Theatre of Cruelty, place him alongside Breton and Brecht in creating the contemporary understanding of avant-garde practice. This new collection, Artaud the Mômo, draws from his last period of writing, during his stay at a sanatorium in Rodez under Vichy France. During this time, he underwent electroshock, and battled his infernal double, the Mômo.

Artaud was born in 1896, and beginning in the 1920s, he developed a practice based in exuberant and vivid imagery. Following his commitment to an asylum, he created a series of works based on a persona called The Mômo. This edition of Artaud the Mômo incorporates works that the longtime translator Clayton Eshleman compiled over many years, alongside previously unpublished letters by Artaud that give greater perspective on his understanding of the work. Much of it has previously appeared in the 1995 edition of Watchfiends and Rack Screams, but there are changes to this printing that make it exceptional.

Eshleman has been a champion of surrealist tendencies in poetry, beginning in the 1960s. He published many works of poetry within a cohort supported by Black Sparrow Press. He edited Sulfur magazine. And through the years became one of the principal translators of Artaud and Cesar Vallejo in English. Like Artaud, Eshleman is a student of human history and anthropology. This manifests in writing like, Jupiter Fuse, a collection that examines cave paintings.

I will share some simple facts from Eshleman’s introduction: Artaud was born in 1896, and as a child he suffered from meningitis, which led to prolonged illnesses, including debilitating headaches. At the age of 15 he claimed to have been attacked by a pimp in the street, the first of a series of attacks that were alleged, and contributed to an inevitable diagnosis, “attack syndrome.” Artaud was institutionalized beginning at a very young age, living in clinics from 1917-1920. His prominence in literature is defined by the period 1920-1936, when he lived in Paris, contributing to the Surrealist project, and developing his signature poetry and dramatic practice, including Art for Art and Theater of Cruelty. He was in films, such as Dreyer’s Jeanne d’ Arc, and Abel Gance’s Napoleon. And he began his project with works like Celestial Backgammon, The Umbilicus of Limbo, and Nerve-Scales, as a mix of drama, poetic fragments, and writing on literature. His pronouncements and manifestoes were contagious: “All writing is pig shit.”

Between 1924-1926, Artaud was a formal member of the Surrealist project, contributing to La Revolution Surrealiste, and running the Surrealist Research Center, before his sensational and historic expulsion for his heretical adherence to the bourgeois art of theatre.

After this, he continued his work, including travels in Mexico to study the Tarahumara. In 1937 Artaud was institutionalized. These writings come from his prolonged institutionalization in Rodez. They reflect two of his nine years in institutions.

Artaud the Mômo is a fierce collection. The language is violent and pornographic by contemporary standards. The figures of his imagination are tormentors and mythical persona. The content features the principal figure of The Mômo , the double that Artaud created within his convalescence. It contains glossolalia, imaginary hermetic language, and scatalogical word play. The chief fascinations of Artaud the Mômo include self ontogeny, and the role of creation within mythical traditions as an opportunity for hermetic and occult authority. The translation has been well documented through the years, and this edition features a paired French/ English comparison.

Stephen Barber, the edition’s editor, draws on previously unseen letters to the original publisher Bordas to paint a vivid picture of Artaud’s final days. Artaud, able to leave Rodez for Paris, was brushed off by the publisher, his secretary wouldn’t allow him an appointment. Artaud wrote, “Sir, I am very ill… So I can almost never come into Paris…but my name is Antonin Artaud and you have published one of my books entitled Artaud the Mômo which has just sold out in the space of single days…you have made a killing with Artaud the Mômo picked up a fortune all that stinks ”

Barber goes on to explain that this translation of Artaud the Mômo was based on information Paule Thévenin received from Artaud, including post-scripts and hand written addendums.

It’s a moving work, Artaud circled his double, and the place after life:

“A blank page to separate the text of the book, which/

Is finished from all the swarming of Bardo/

Which appeared in the limbo of electro-/

shock.”

When Robert Walser entered the sanatorium he said he wasn’t there to write, he was there to be mad. But Artaud wrote. Althusser spoke of the genius, the lucidity that comes from Artaud’s madness.

“Every historical period has laws… but they can change at the drop of a hat, revealing the aleatory basis that sustains them, and can change without reason…This is what strikes everyone so forcefully during the great commencements, turns or suspensions of history, whether or individuals( for example, madness) of of the world, when the dice are, as it were, thrown back on to the table unexpectedly, or the cards are dealt out again without warning, or the ‘elements’ are unloosed in the fit of madness that frees them up for new, surprising ways of taking-hold…(Nietzche, Artaud). Louis Althusser, The Underground Current of the Materialism of the Encounter.

Artaud presents the impossibility of art. His strained relationship with his uncanny double, The Momo, is corporeal and metaphysical, and essentially highlights the truth in the paradox around thinking, experiencing, and mental illness. He shows there is a world beyond a dualism of psychotherapy and pharmacology. But the truth of the unruliness of bodies, the inevitable breakdown of our bodies, does not dispel the bitterness. Because there can be no consensus on the metaphysical aspects of schizophrenia, the avant garde has consistently fetishized “madness.” Breton’s Mad Love, the Surrealists on through Jarry’s Theater of the Absurd, on to Zulawski’s ultra cinema. In Zulawski’s Szamanka, psych ward patients are juxtaposed against a mythologized shaman. The question has always been present about the limits of the mind. Certain trends in the avant garde appear perverse, in stark relief against suffering bodies. And yet the perversity too is part of the mystery. Madness and genius. The obscure founts of inspiration gurgle. And Artaud is the essential mad genius.

In 2020, the legacy of this work must be treated both as a looking at and past the dialectic of a genius body breaking down. There are so many smart incisive accounts of contemporary people living with and around psychosis, including Marin Sardy’s The Edge of Every Day, and Sarah Townsend’s Setting the Wire. In a 2020 interview with the Rumpus, Sardy says, “Schizophrenia magnifies that, that fragmentary nature of experience.”

Sardy identifies this as one of the central reasons artists, and the avant garde, attaches to this experience. It heightens the fragmented experience of the world, the breakdown of language, and tradition. And by doing so, makes the world unfamiliar. This is, of course, a central tenet of Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty.

Artaud was the essential modernist, living in a body torn apart, embodying art. This collection captures his final desperation.

POETRY

Artaud the Mômo

By Antonin Artaud

Diaphanes

Published October 30, 2020

[ad_2]

Source link