[ad_1]

A middle-aged white woman walks down the street to the grocery store and convinces herself that she’s different than the other women she’s passing by. That the self-reflexive thoughts she’s having, the awareness of being a privileged white person, who voted for Hillary Clinton, and didn’t want any of this to happen, and has spent four years angry and hurt by the pain in the world, separate her from all those around her. And yet. . . Dana Spiotta reckons with this “yet” in her new novel, Wayward. The story follows Sam, a woman in her 50s who seemingly all of a sudden leaves her husband, Matt, and 17-year-old daughter, Ally, and moves to a cottage closer to the heart of Syracuse, away from the suburbs they’ve resided in for so long. This “yet” follows Sam around no matter how far away she moves, or how much she changes her routines or the number of protests she marches. After all the Facebook groups she joins, and new friends she makes, she is still a middle-aged white woman, the most invisible of people, the least-thought about sort of person, and yet. . .

“She understood why the world despised comfortable older white women—and age was the point—even if they didn’t vote for him, they had been around long enough that the horrible state of things was partly on them. It was.”

After Sam’s departure to her new home, her and Ally’s relationship deteriorates as the distance between them expands. She continues to text her daughter each night, but no answer ever comes. Instead, she sleeps in front of the fireplace in her drafty fixer-upper, and thinks about her life as a mother, and how that has both defined and controlled her existence.

“Why had she wasted so much time, expended so much energy on this endless, fruitless, pointless questioning of her parental inclination? Time that could have been spent clutching the little body to her, comforting her daughter while she could still be comforted, before she grew up and they both become, well, uncomfortable?”

The novel switches between Sam and Ally’s perspective. Sam dives further into an attempt at living her own, isolated life, much of it online early on in the story, as she realizes the true appeal of social media: the fun of the internet is obsessing over your own interests and new ideas, and deriding others for theirs. Underneath this though, is a battle inside Sam to decipher her place in the world. How does a middle-aged white woman move through the world? How does she present and direct anger appropriately and in a genuine-seeming way? At both the personal level and collective, social level, these frustrations are not given a care in the world, and maybe rightfully so, but the issue remains of where does this anger go? What is it to be used for? All the while, Ally is dating a 29-year-old who works with her father, and is discovering for herself what it means to live an isolated, adult life, away from the teachings of her mother.

“She [Ally] had read her Sartre, but she had also read her Kant, and she had her Rawls. Or in any case, she had their Wikipedia pages, which were quite extensive. She knew what bad faith was. What all the concerned adults advised was degrading, crude. Such as, if you do send a naked pic, never show your face with your body. Again, so cynical. They actually want you to disembody yourself, separate your identity from your body to ‘protect’ you. Everything is doomed if you expect so little of the world.”

For much of her arc, Ally’s issues are ones that her mother could answer and help her through, but as they both reckon with what it means to consider themselves new people—even if they haven’t changed very much at all. Spiotta’s novel does an impossible task. The depiction of middle age and motherhood, of divorce and Facebook groups and Medium posts to sign to cancel friends, of a shooting of an unarmed boy by the police as Sam walks around town, the realization that the people walking around you at the State Fair aren’t “good ole America” and they also aren’t strictly gun-toting, racist rednecks either—all the clichés are there and yet Spiotta effortlessly shows this as the very tangible, very American reality that it is.

In the same way that Ben Lerner writes about art, and Rachel Cusk writes about her own views on motherhood and family, Spiotta avoids the clichés and corny nature of these topics, and injects a palatable sense of realness to these normal affairs of life, of growing old in the world and in relationships and the changing nature of parenting. She accomplishes this in a supremely polished and measured prose that strays away from the more DeLillo-heavy style of her previous work. Wayward is a novel that captures middle age in all its charms and ugliness, in a way that seemingly only her and a few authors could manage. None of the realizations in the book are epiphanies for Sam. They are simply altered viewpoints from a place of ignorance, of comfortability and white suburban living, to one actually in the world. Straying waywardly from the lifestyle we expect of those we don’t really see isn’t groundbreaking or transgressive, it’s a capturing of life lived in pursuit of expended emotion, anger and happiness and pain all actually lived and felt away from the safety of a television and a phone screen. In the end, as always, it’s all about choices.

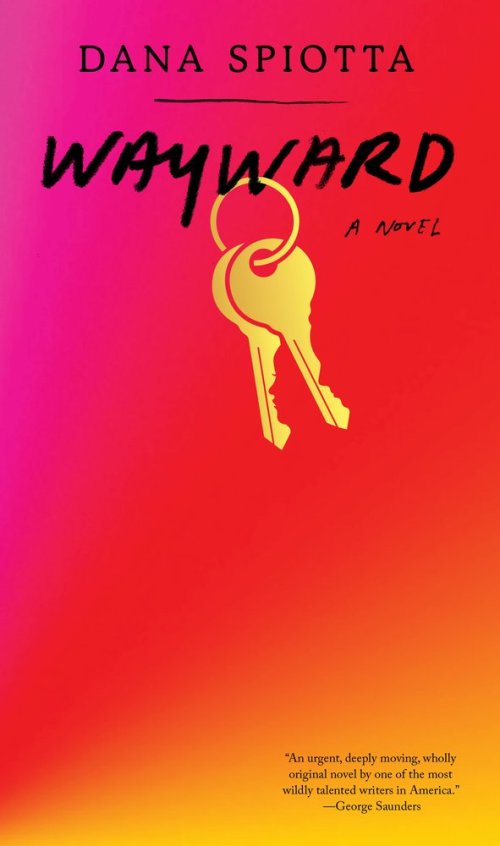

FICTION

Wayward

By Dana Spiotta

Knopf Publishing Group

Published July 6, 2021

[ad_2]

Source link