[ad_1]

There are worse things than a local gangster’s cronies lurking in New Jersey’s wetlands…

It was a June night, warm but breezy. Lynn and the kids had gone to bed, and I was sitting out next to the giant rose bush with my neighbor Phil. The back of our house faced across our small yard and garden, to the side of the Victorian his dad had left him. We were drinking beer and smoking cigarettes and weed. He was telling me stories about his father who’d been a homicide detective in Camden, and about his cousin Donny, whom he described as “the walkin’ prince’a death.” The big old house, due to its poor upkeep, seemed like it could have been haunted. The cousins were both heroin addicts. Still, Phil was a pretty good neighbor, nice to the kids and Lynn, and Donny, back when he lived with his cousin, volunteered once to climb to the roof of our house, since I’m afraid of heights, and patch a hole near the chimney where bats were getting in at night.

At a lull in the conversation, I threw Phil my ghost story question. Back then I liked to ask people if they’d ever seen a ghost. It usually made for interesting conversation and, of course, I was chumming for story ideas.

He sat thinking for a while, and said, “There’s a shitload of roses on this bush.”

“I know, it’s gone insane. What about ghosts? You don’t even need a ghost, all you really need is a haunting.”

He shook his head, smiled, and said, “I don’t think anyone would call this a ghost story, but, you know, it’s in the same ballpark.” Phil hit a joint and said, “Donny’s crazy. You know that. He used to have a lot of wacky ideas and plans. This was back in the days he lived here with me. Once when we were dead broke for a long time, Donny came up with the idea to rob this old woman who lived over by the park.

“‘How do you know she doesn’t live with anyone?’ I asked him.

“‘I’ve sat in the park and watched her place,’ he said. ‘She’s alone, for sure. All we have to do is distract her. I’ll get her attention and you slip inside while she’s talking to me and get whatever you can get.’

“We hadn’t used in a while, and by then, that damp turd of a plan sounded like genius. So, we waited until it got dark. Those were rough hours. When we got down to it, I took up a position out of sight behind the hedges planted along the front of her place. Donny went to the door. If I heard him talking to the old lady and it sounded good, I was supposed to slip around to the side and back doors and give them a try. I was armed with my trusty paperclip that could work on just about any lock if you knew what you were doing.

“Donny rang the doorbell and a few seconds later the woman opened the big wooden door. ‘What do you want?’ she asked in a cranky voice, and instantaneously, he punched her right in the fucking face. I saw her glasses fly off and she dropped like a lead balloon back inside the house. Right there, I was ready to bag the whole thing. I mean, I’m a scumbag to some extent, but I want you to believe me, I have my limits. I’m not about punching old ladies. But then, before I knew it, he was back outside with a handful of money, two pockets full of jewelry, and a fresh pack of Marlboro Reds. We ran like hell.

“As we were hightailing it, I realized that we had just robbed a woman who lived only across the park and two blocks east of me. It was just starting to dawn how deadbolt dumb the entire operation was. Wouldn’t you know it, we were tearing across the park, and we almost ran into this guy Postlethwaite, a massive tub of human goo, in front of the gazebo. Probably walking home from a feast at the Golden Dragon. He said, ‘Where you asswipes heading?’ We told him we were out for a jog, and he started laughing. We didn’t stop to chat.

“Later that night, we eventually scored, and once the edge was off, I got scared. I was also pissed at Donny for hitting the old lady. I kicked him out of the house. And we’d been tight. Both sets of our parents crapped out in the first leg of the parent race, but me and him made a bond at fifteen and stuck together. I told him if I got nailed for the robbery, they could put me away and take the house from me. The mortgage payments are only like five hundred a month, but I was having trouble scraping that together after an accident at work where I hurt my back. Donny took it hard, but he left after only breaking some furniture.

“A couple of weeks went by, and I swore the cops were gonna appear out of nowhere and grab me. I decided to get off the stuff, so I went through withdrawal, at least tried to control the habit some. Who was I kidding? It turned into a fight to the death. Gagging, puking, sweats and tremors and hallucinations. I’d wake in the morning and feel like someone had beat me with a stick. Finally, I said fuck it and decided to score.

“I’d been off for almost a week. I left the house in search of. There was an apartment on the third floor over NCS, you know, the appliance repair place downtown, where a girl pretty reliably sold fifteen-dollar bags of cut-with-flour shit I used to get for ten. Any port in a storm, though. It was a nice spring night, and I was blazing along the sidewalk in a rush to get off. That’s when I noticed a car moving alongside me.

“I stopped and watched while it sped up for a few yards and then came to a full stop. It’s never a good sign when a car pulls over in front of you and all six foot five inches and three hundred and seventy pounds of Postlethwaite gets out holding a nine-millimeter pointed at the ground. He reached out and opened the back door for me. ‘Get in, Philly,’ he said. I thought of bolting, but the giant would have shot me in the back no problem. I’d seen him in action going to town on some loser who’d stiffed his boss, Mr. Marfen, who owned part of the heroin trade in Camden.

“‘What’s going on?’ I asked him.

“‘Get in the back,’ he said. Lifting the gun into my sight, he used it to wave me toward the door. ‘Don’t be stupid.’

“As I moved toward the car, my mouth went dry, and my throat closed. My legs were trembling. I slid through the door onto the back seat, and Postlethwaite said, ‘We got some company in there for you.’ It was Donny, who stared straight ahead like a zombie. The whole thing was a nightmare. The door slammed shut and locked. The big man got into his seat up front, and we were off.

“We went through town, and then Postlethwaite turned around. His head rest had been removed and he draped one folded arm over his seat. He had the gun in the opposite hand. ‘You two jerkoffs have gotten yourselves into deep shit now. Slacks’—he pointed with the gun at the driver—‘and I have been employed to deliver your bodies to the Meadowlands.’

“‘What are you talking about?’ I asked him.

“‘Come on. I saw you running through the park that night, running from having robbed Mrs. Marfen’s house.’

“‘Who’s Mrs. Marfen?’ asked Donny.

“‘You know who Mr. Marfen is, well, Mrs. is his mother. You socked Marfen’s mother in the face.’ Slacks and Postlethwaite laughed. ‘You’re some real simpletons.’

“‘You’re going to kill us?’ I said.

“‘Now what do you think? We kill you and toss your bodies in the marsh. It’s business, you know, nothing personal.’

“Right then we entered the turnpike north ramp and sped out of South Jersey. I was swamped, couldn’t speak or think. I experienced a half-assed version of my life passing before my eyes. It was what I’d always imagined drowning felt like. Postlethwaite turned around to face the windshield, and I tried to look at Donny to see what he was thinking, if we were going to try anything. There was nothing I could do alone, but Donny was made of rock. If Postlethwaite didn’t have a gun, his neck would have already been broken. These guys were really going to kill us, and we were going along with it so far like it was a Sunday drive.

“Donny was my only salvation. Still, if it wasn’t for him, I wouldn’t have been in a jam with death hanging over my head. As much as I loved him, I knew right there that I was going to have to give him the heave-ho if I somehow got out of that mess. For the longest time, I mean miles and miles, I was in a daze, half dope-sick, half scared stupid, thinking about how I was going to get my life together and be a good person as soon as we escaped. You know, ridiculous,” he said, and laughed.

I said, “She would have been a good woman if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.”

He nodded. “That’s about fuckin’ it,” he said, and passed me a beer. “So, we were driving along, and suddenly, Postlethwaite spun around and said, “You guys are in luck.”

“‘How’s that?’” I asked hoping he was going to tell us he’d let us go.

“‘You’re gonna be part of our experiment,’ said Slacks, smiling into the rearview mirror.

“‘We’re going up to a spot on the Hackensack River where it turns into a marsh. In Secaucus, across the river from the racetrack,’ said Postlethwaite. ‘You know anything about that area?’

“I shook my head and Donny just sat there like the mannequin he’d been for the whole trip.

“‘It’s polluted as shit,’ said the big man. ‘We’re talking tons of chemicals, industrial and military waste, just a giant cesspool of horror.’

“‘At the top of the list of Superfund cleanup sites,’ said Slacks. ‘They used to say that it makes the bodies decompose faster. That’s why they started taking stiffs there. But you remember from the dinosaur movie …. . . Love finds a way.’

“‘Not love, you idiot,’ said Postlethwaite. ‘Life finds a way. You have all that heinous jazz there bubbling up and then throw life into the mix, and what you get are these flesh-hungry giant newts, big as a man, that occasionally go upright,’ said Postlethwaite. ‘We call them Stumps, cause they’re dumber than you two.’

“‘They’re gonna tear your throat out and just keep chomping until they see daylight through your asshole. Ferocious motherfuckers,’ Slacks said.

“‘Are you for real with this?’ I asked.

“‘Swear to God,’ said Postlethwaite, putting his gun hand over his heart. ‘Nothing clears up the bodies like these things. They’re fucking awesome. We could sell them to the government. Their teeth go through bone like it’s marshmallow.’

“Two minutes later we were pulling over in front of a waste plant somewhere in Secaucus near the Hackensack River. It was cold out, and I was shivering uncontrollably. Before we headed behind the plant, through the six-foot weeds, they zip-cuffed Donny’s wrists in front of him. He looked like he was praying, but I knew he wasn’t. There was no need with me. Slacks had a gun on me, and I was too scared of dying to think about how to stay alive. Postlethwaite led the way with a flashlight on a trail that wound behind the plant down to the river’s edge.

“The boat they had staked there was a thirty-foot aluminum flat-bottom. It had a lot of room, useful for ferrying bodies, I guess. From where we boarded, I could see the silhouette of the marsh less than a hundred yards out across the flow of the river. Trees and bushes and tallgrass. We pushed off. The boat had a small electric motor that was in no hurry.

“We crossed the Hackensack and then entered the wetlands, a maze of tiny islands of cord or sedge grass, some with fucked-up arthritic trees, sticker bushes with thorns as long as your finger. In some places along the meandering course, we’d come to a spot where the river ran more fully, and the islands were larger with taller trees. Donny and I were sitting on the middle seat, facing forward at Postlethwaite’s huge back covered in his shitty gray raincoat. Slacks was behind us at the outboard paying attention to steering around the islands.

“The big man had left the flashlight lit, lying on the seat next to him, the beam pointing back at us. For the first time since we’d left South Jersey, Donny turned his head toward me. I looked over at him and he winked and gave a very subtle nod. Immediately, I panicked because I had no idea what he meant by that. Was it Don’t sweat it? Or was he implying I should be ready to rumble? Before he turned his face away, I tried to see what I could in his eyes, but even with the flashlight, it was still too dim in the dark night to be sure.

“When Slacks left the middle of the watery path and headed toward a larger wooded island, I somehow knew that Donny was going to make his move as Postlethwaite tried to get out of the boat without falling on his fat ass. The prow scraped ashore on a small spit of sand. The engine died and I almost crapped my pants in anticipation. But nothing developed, on any front. Postlethwaite got out as graceful as a ballerina, and Donny followed him. I stumbled getting over the side and fell in a half a foot of poison marsh water. Slacks grabbed me by the collar and lifted me to my feet. I thanked him. ‘Move it along,’ he said, and waved his gun at me.

“By this time, I was thinking, you know, we were going down to the wire. Maybe I should make a break for it on my own. Maybe the face Donny made was just him saying goodbye. I thought about it that way and didn’t like it but knew it could have been true. We took a path through a gnarled forest of leafless trees, to a large pond that glowed slightly orange.

“‘The Stumps have a city down at the bottom of that pond. Get a load of the color,’ said Postlethwaite. ‘I’m going to shoot one of you, and the noise will bring them swarming to the surface. Over time, and all the stiffs they’ve chowed down on, by now there’s nothing they like more than gobbling human heads and asses. They eat the rest too, but not with the same savagery. Evolution is more than a theory.’

“‘After that part,’ said Slacks, ‘when they rise up and eat whoever just bought the farm, we’re gonna leave the other guy alive, and standoff at a distance to see if they’ll eat a live person. To this point we’ve only seen them eat dead bodies, like turkey vultures would. But me and Posti have a theory that they’ll now attack and kill for human flesh.’

“‘You two fuckin guys,’ I said. ‘Do you hear what you’re saying?’

“Postlethwaite laughed and said, ‘I know . . . brilliant.’

“Sudden as a striking snake, Donny took a flying leap and wound up with his zip-tied wrists around Postlethwaite’s beefy neck, riding the giant’s back like a ragdoll. In the lightning surprise of it, the big man dropped the flashlight and squeezed off a shot, but it went wide.

“No one could see a fucking thing. The gun went off again, and I ditched onto the ground. Again, it went off, and this time I seriously heard a bone crunch upon its nearby impact. A weird sound followed, which turned out to be Slacks crying like a baby.

“I rolled to the flashlight, then took a chance and stood up. Donny was still in the process of trying to strangle Postlethwaite. The beam found Slacks curled up on the ground, crying. The hole in his leg where the bullet went through and shattered his femur was still smoking. Luckily, he’d dropped his gun. I retrieved it and told the big man to cease and desist. He was so out of breath by the time I got him to give it up, I thought he was going down for sure. Somehow, Donny had broken the zip tie and his hands were free. He disarmed Postlethwaite and punched him in the face a few times to simmer him down.

“The giant took the hits, shook them off, and said, ‘Listen, the gun was fired, those fucking Stumps are going to be here lickety-split. If we leave Slacks for them, we can get away. If we try to carry him, they’ll catch us and then we’re going to find out for real if they’ll eat living flesh. Who’s for leaving Slacks?’ said Postlethwaite.

“‘No problem,’ I said.

“‘My pleasure,’ said Donny.

“‘It’s unanimous,’ said the big man.

“All the time, Slacks was begging us to have mercy and take him with us.

“‘If you don’t shut up,’ said his partner, ‘I’ll shoot you again. Just lay there and take your lumps.’

“That’s when the pond hit a full boil. There was something coming up from below. We ran down the path to a point where we could still make out Slacks with the flashlight and hid behind some dead trees.

“‘Keep your eyes peeled,’ said Postlethwaite, “and you’ll see I wasn’t kidding.”

“We couldn’t see a damn thing, really. We just heard Slacks screaming to beat the band and even at the distance we were from him, I could hear munching, like the sound of somebody eating a roast beef hoagie in a dark kitchen. It wasn’t long before sounds of teeth biting bones and the screams became whimpers. ‘Let’s get the fuck out of here,’ I said.

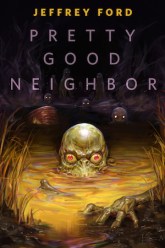

“I turned to find the trail with the flashlight beam and instead I found, standing right behind us, a crowd of those things from the orange pond. They had blunt snouts and goggle eyes, and the width of their heads was the width of their necks down to shoulders and arms (I guess you’d call them); thick thighs and webbed feet with four toes, but big ones, pads on the tip of each one. Picture all that wrapped in a pale olive-green frog skin with tinges of orange, and you have the Stumps, except for one crazy detail: they had human junk. Like the one standing in front was carrying a club made out of an old, rotted table leg. He had a dick and balls, no exaggeration. Next to him, the queen? You know—vagina, etc.

“‘They’ve changed a lot since the last time we fed them,’ said Postlethwaite. ‘Looks like they’re all walking upright, and jeez, what’s with the balls and so forth? That’s what I call evolution.’

“‘Yeah but are they gonna eat us?’ asked Donny. He held his gun up and at the ready.

“I held the flashlight at their eye level, and they lifted arms across their faces, squinted, and turned slightly away. I also had Slack’s gun aimed at the closest one.

“‘Wait a second,’ said Postlethwaite, who stood on the other side of Donny from me. ‘That guy there, look at him. Does he remind you of Westfelt? I swear he looks like him. Sure, he’s a salamander on two legs or whatever the fuck, but that forehead and those jowls.’

“‘He does look like Westfelt,’ I said. ‘He’s even got that mole on his left cheek. What ever happened to Westfelt?’

“‘Me and Slacks brought him out here and fed him to the Stumps. He ran afoul of Marfen.’

“‘So, what are you saying?’ asked Donny.

“‘They must have ingested his DNA and it became part of their evolution.’

“‘Fuck that,’ said my cousin. ‘When you hear a gunshot, Phil, count to six and then just start running. If one of these things gets in the way, blast it. Go for the boat. Don’t run before counting.’

“‘What’s the plan?’ Postlethwaite demanded.

“Donny turned and gut-shot the big man, who fell backward. When he did, the Stumps started forward en mass. The wound was crazy bleeding, and Posti yelled, ‘You fucker, Donny. You fucker.’

“I counted toward six but got to five and ran forward. Most of the folks from Stump City had passed me heading for the wounded tub of human goo. One of those things snapped at me as I tried to get past it, and I didn’t hesitate to shoot it in the face. I heard Donny’s gun go off again and again. And then he was behind me, and we were running down the trail. I turned back for only a second, pointed the flashlight, and caught a glimpse of Postlethwaite swinging mighty haymakers, clocking the Stumps’ rubbery heads as they dove in, teeth chomping for the big man’s big head and bigger ass.

“‘Don’t stop,’ Donny said. ‘As soon as they finish with him, they’ll be after us.’ Screams of agony chased us to the boat and all the way home.

“If you don’t believe me,” said Phil, “I understand. It seems farfetched, but I swear to God, that’s what went down. After we got back to town, we had to lay low, as word on the street was that Marfen was looking everywhere for Postlethwaite and Slacks. Reportedly he was nervous without his goons, so he wasn’t out looking for trouble. As long as that lasted, we’d be safe. After we got back, I didn’t hear from Donny until a few months later. It was the end of the summer, and he told me that he’d been diving in the Delaware River with only flippers, a mask, and a snorkel. With a long rubber hose hooked to an acetylene torch, he was cutting the brass off a sunken ship.

“‘That’s a crazy man’s job,’ I told him.

“‘It pays amazing. And I liked being in the water all summer, but I’m gonna need to find a place to stay through the fall and winter until the work picks up.’

“I knew he was angling to get back in my place, but I didn’t want him. I’d spoken to a friend of ours who’d been to the trailer where Donny lived next to the river. The report was that he was diving during the day and snorting a coke/heroin mix at night accompanied by a pint of Mr. Boston Mint Gin and voluminous packs of Camels. The trailer the salvage company rented him had holes in the floor, and while he slept rats came up through them to get at his leftovers. That trip to the Meadowlands cured me of him. I talked to him until he mumbled too much for me to understand and I quietly hung up.

“A few days later he called late at night, told me he had one week to work and that he needed a place to stay for the fall and winter. It was already the beginning of October, and the thought of him in that dark, freezing water made it difficult for me to turn him down. Then he went on and told me he was being stalked by a large fish or something. Whatever it was, he didn’t get a good look as the river water had been murky the last month, but it trapped him in a room of the sunken ship once for crucial minutes, to where he barely made it to the surface for air.

“I told him to ditch that job, and then he pleaded with me to take him in. I held the phone against my chest as he begged. I couldn’t hear him, but I felt it in my heart. Eventually, I just hung up and turned my ringer off. Later that night, after using, I had a kind of vision of a memory. It was all wavy at the boundaries and the noises were exaggerated, but it was the time Donny got between me and my old man when he was beating me with his belt. I had done something wrong. My father was loaded and turned his anger on me. Donny decked him, a Camden city detective, and helped me outside, where we ran, him holding me up by the shoulder.

“The last time he called, he sounded frightened and incredibly high on a powerball, no doubt. My girlfriend was over, and I didn’t want to bother with him. He said, ‘Postlethwaite is back, banging on the door of my trailer right now.’

“‘What are you talking about?’ I said. ‘How fucked up are you?’

“‘There’s a naked, pale green Postlethwaite at my door. He keeps repeating ‘Fuck you, Donny. Fuck you!’ in a voice you’d use to order a cup of coffee. He came out of the river.’

“‘How’s that possible, Donny?’

“‘I don’t know. Maybe, like Slacks said, love found a way . . .’

“That was the last thing he said to me. The line went dead, and I was glad it did. But my conscience started to get the better of me, and at the end of the week I went out to where his trailer was next to the Delaware to invite him to stay for the winter. It was overcast; it was cold. I pulled up next to the trailer. There were whitecaps out on the river. I got out of the car and went up the steps. I banged three times on the door and called out his name. Leaning over the railing, I peered into the side window.

“I was about to knock and call out again when I saw an enormous pale form, lumbering through the trailer’s shadows like a fish in murky water. That was enough for me. I ran to the car, put it in gear, and never looked back. From right there, I was sure Donny was gone.”

“A ghost story and then some,” I said.

Phil looked exhausted and had tears in his eyes. “At least a haunting,” he said. We each had a last beer and then packed it in.

No more than a week and a half after that night by the rosebush, Phil and his girlfriend, Margie, shot up over at Phil’s place. She died of an overdose, and the next day they carted him off to prison. The last I saw of Phil was from my kitchen window. The cops were leading him out to a wagon with his wrists zip-tied behind his back.

“Pretty Good Neighbor” copyright © 2023 by Jeffrey Ford

Art copyright © 2023 by FESBRA

[ad_2]

Source link