[ad_1]

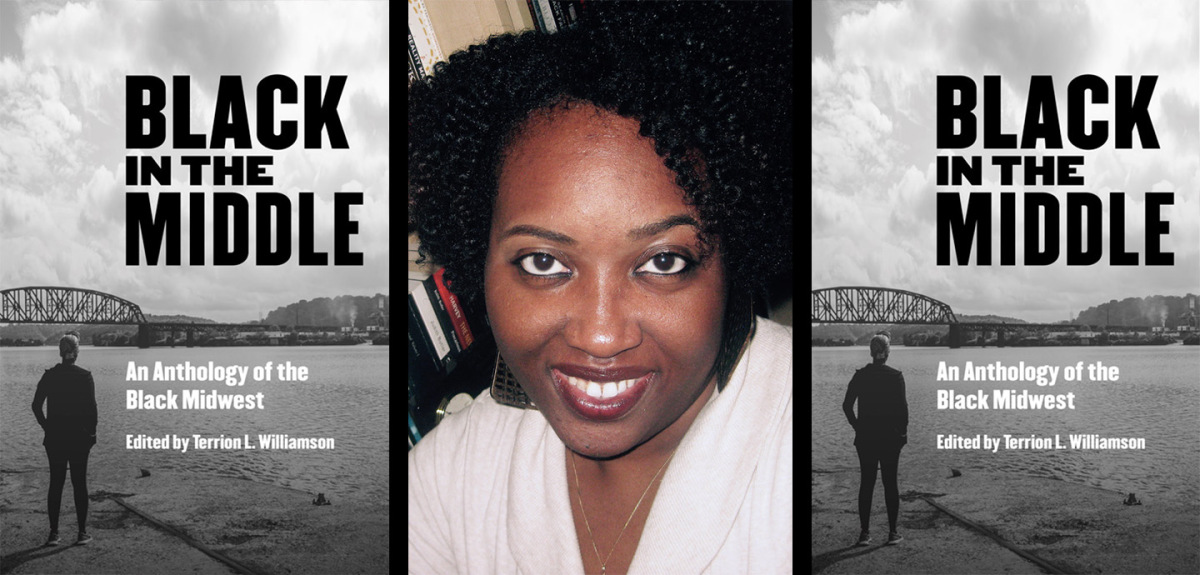

Black Midwesterners live complex lives full of love, creativity, and community; but, that’s not usually the story told in mainstream depictions of Middle America. In 2017, scholars, artists, activists, and students banded together at the University of Minnesota to form the Black Midwest Initiative to promote work that more accurately captured the truth of lived Black experiences. Politicians and the media had long erased Black Midwesterners from the national conversation, spurring Terrion Williamson, the current Director of Black Midwest Initiative, to begin plans for the Initiative well before the 2016 presidential election. In the wake of the election, the Black Midwest Initiative took form and in October of 2019 they hosted a symposium and organized the publication of Black in the Middle: An Anthology of the Black Midwest to continue the conversations that sparked there.

Williamson, who is also the editor of the anthology, committed to including artists across different landscapes. Poets, visual artists, sound artists, and filmmakers all contributed their words, art, and photography to the project. Williamson also purposely chose Belt Publishing, an independent press outside of the academic space, to elevate a range of voices. She wanted to profile a myriad of social actors; Black in the Middle centers their stories and gives them the stage they deserve. In June, I spoke with her about her vision for this timely, compelling collection that allows predominantly Black Midwesterners to reclaim their home, histories, and future.

Jen Cox

Black in the Middle is comprised of individual stories from individual people, but what themes emerge across the essays and stories?

Terrion Williamson

One of the most evident themes is visibility, particularly in the moment that the Initiative came into formation after the 2016 presidential cycle. I was feeling — and many of the people involved in both the Initiative and this book were feeling — as if the discourse around the Midwest or “Middle America,” as it related to the presidential cycle, really left out a lot of the stories that we know best. The narrative around Middle America at that time was essentially about a working-class anger, very often described as white and male. The righteous anger of the manufacturing class, of blue-collar workers, is supposed to have been what heralded the emergence of Donald Trump, but that narrative largely leaves out the experiences of Black folks. What I and other people in this region have seen and felt most forcefully was that Black folks were among those who were first and hardest hit by the different socioeconomic changes that have occurred over the past several decades throughout the region. And so I think that shows up fully, this idea of the erasure of Black voices and experiences in popular narratives of the Midwest.

Additionally, there is a missing narrative around the richness of Black life in the Midwest. Part of the impetus for this work is challenging the idea that most good things that come from Black people or people of color come from elsewhere — like the coasts. There is a dearth of attention to the rich Black cultural production that emerges out of the Midwest. It’s really obvious when you start naming people who are well-known or culturally influential, there’s a whole host of folks, but there’s a way in which people have been displaced from their Midwestern roots. For instance, few people would deny how important Toni Morrison is to American letters and American literature, but she’s sometimes been displaced as a Midwestern writer. Or the way that somebody like Richard Prior gets so much of his material from his childhood years growing up in Peoria, Illinois, and yet that’s often left out of his story. Biographers never forget to mention that Pryor was raised in brothels in Peoria, certainly, but so much of what made his material culturally viable was shaped by his experiences in his hometown — and his hometown, our hometown, has also worked to displace him in some ways. The Initiative and the book project are recovering those narratives as well. We’re making visible the struggles we’ve had, but also the successes and impact that Black Midwesterners have had across the American landscape and cultural productions.

Jen Cox

You talked about visibility, and I think often about how stories allow us to get to know people and care about them, and yet as a culture we’re selective about who deserves those stories and who deserves to experience a range of emotions. Who’s allowed to be angry, upset, and disenfranchised and express it? This is beautiful work because fine, if the mainstream isn’t going to allow specific groups of people to tell their stories in a way where we’re not reduced to tokens, then we’ll do it ourselves. This book is one space for Black Midwesterners. What does it mean to you to be a Midwesterner? I’m from New England and feel so connected to Chicago, but I’m not an authentic Midwesterner, obviously. So I’m curious about what it means to different people and to you.

Terrion Williamson

I was talking to my mentor about this a few weeks ago, and he was pointing it out to me in a way that became very obvious because he knows my work really well. To talk about the Midwest is to talk about class in a really deep way, at least to me, because I can’t have a conversation about Black folks in the Midwest and not have a conversation that’s deeply implicated by class struggle. Class struggle is central to the concept of Black community formations. Part of the narrative that seems to be missing from or that gets distorted in the national narrative is the connection that so many Black Midwesterners have to working-class, under-resourced, inner-city life in ways that are structurally produced. This is what Jason Hackworth discusses in Manufacturing Decline, for instance, the specificity of urban decline, which is always read as Black, in northern industrial cities. So many of us are coming from places like the South Side of Chicago, Detroit proper (not metro Detroit, Detroit Detroit), North Minneapolis — all these communities that get talked about as failing or declining. And even if we are not ourselves working-class people any longer, many of us came from working-class families and communities. So, for me, to be a Black Midwesterner is to be constantly thinking about how I am situated across a range of economic and cultural modalities.

There’s also all this Southernness. My best friend and I grew up on the same street in Peoria and became best friends in fifth grade. We eventually found out my father and his family and her mother and her family all grew up in the same community in West Memphis, Arkansas and even went to the same high school. There are so many stories like that, where there are family roots that go back to the South, but people end up in these Black enclaves in the Midwest. There’s all this connection to southern culture but that functions differently in the cities of the Midwest. It’s about being grounded in an everyday Black sociality that is tied to the land, to particular kinds of familial and communal formations that feel familiar wherever I go. When I lived in East Lansing, Michigan, it felt so much like Peoria, Illinois to me. Not to say all the places are the same, because we’re pushing back against that too, not everything in the middle is the same. These places all have their own character and differences, but there’s also a way in which the kinds of experiences and the way we’ve been shaped by industry and social forces of the Midwest make various locations seem familiar in ways that I find comforting and significant.

Jen Cox

I wanted to ask about those different intersections in your own life, and I know a lot of your work is about Black feminism. I’m curious how the stories that are told in this book compare or complement the work you’ve already been doing. Is that addressed within the text?

Terrion Williamson

There are a couple of pieces that specifically talk about Black feminism. Vanessa Taylor’s piece on Audre Lorde, for instance, gets at the conversation around feminism, and there are pieces such as those by Melissa Stuckey and Gladys Mitchell-Walthour that talk about the role of women in particular in Black communal formations. I also think Black feminism is both an intellectual project and a committed way of being in the world that is concerned about intersections of all sorts. Intersections of class cannot be separated from talking about race or gender. Many of us do that in the work even if we don’t explicitly name it as feminist work.

Black feminism is also about being deeply committed to respecting the various ways people come to the work, and that is what both the Initiative and Black in the Middle are doing. To come from a Black feminist tradition is to be intentional and clear about the kind of privileges that we have. We’re also very intentional about working beyond the university and making sure there are people in the book and in our group who work at other institutions and outside of institutions altogether. We have to check ourselves and make sure we are learning from those other forms of intelligence that come from beyond the formal universities. We make this central to the work that we do. Even if we’re not explicitly talking about Kimberlé Crenshaw or, you know, pick your Black feminist icon, we are taking what we learned from Black feminist thinkers and applying that to the work that we do.

Jen Cox

I do think this book has mass appeal and really anyone who is interested in any type of American experience should read it. As a white transplant to the Midwest, I feel like it’s not only my responsibility but, also, my sincere desire to know my new home and the people who shape it. But, I am curious: who is your ideal reader If you had to pick one person, who do you hope this book reaches the most?

Terrion Williamson

You’re right, I do hope that it has mass appeal and I can think of all different types of audiences. There’s not just one person but, if I have to pick just one, I want to speak to the young Black person growing up in Gary, Indiana who doesn’t see themselves in any kind of meaningful national narrative. I want us to be speaking to other Black folks in this region, particularly those in places that never get talked about as part of the national conversation, except to be viewed as a narrative of decline, decay, pathology. People need to see there are others of us who come from communities who are doing meaningful work in our lives and we’re not all talking about getting out. There are some who leave, and that’s okay, but there are many of us who stay. I don’t live in Peoria anymore, but it’s home and it shows up in my work all of the time. It’s a beloved place for me. That’s my homeplace and I might criticize it, but that critique comes out of a deep desire to make it better, a deep commitment to making it better for the people who are there.

Jen Cox

You’re allowed to critique it!

Terrion Williamson

Exactly! So do I want a white person who doesn’t understand what it is to be a Black person growing up in, say, Akron, Ohio to pick up Black in the Middle and read it? Absolutely. But so much of our writing is writing towards Black people who need to see others of us, especially those of us beyond Chicago and Detroit — the two cities that loom largest when talking about the Black Midwest, who are deeply committed to our homeplaces. We have both criticisms and a whole lot of love for these places.

Jen Cox

The book’s publishing date was September 1st. We are in this current moment reckoning with the police violence that killed George Floyd and hurt so many others. We’re seeing uprisings across the country. Not that any of this is new in terms of racial injustice or violence against Black people — this is not a new moment — but it does feel different to me this time in part because we’re quarantined and don’t have the excuse of being distracted by other things in life. I don’t think you could have imagined that the publishing date would feel the way that it does right now. What does that experience feel like?

Terrion Williamson

It’s all been just so surreal, so unexpected. This book has been in the works since last October. I sent it off and wrote the introduction in February. It does feel different and I’m concerned about something we’re losing a bit: I think it’s important where it all originated. This particular moment started in Minneapolis. The Black Midwest Initiative put out a statement and what we wanted to be clear on was that it matters that it happened in Minneapolis. If you think about some of the most recent high-profile uprisings or police-involved cases, they’ve occurred in the Midwest. Think about Ferguson and the killing of Michael Brown and the murders of Jamar Clark and Philando Castile here in the Twin Cities in just the past five years. Think about Tamir Rice and Laquan McDonald in 2014 and Rekia Boyd two years before that and Aiyana Jones two years before that. There’s a correlation between the violence Black people are experiencing and these indexes that are naming the “worst places to be Black.” Most of those so-called “worst places” are in the Midwest. And a city like Minneapolis shows up on the “worst of” lists for Black people at the same time that it is named one of the most livable cities in the country. Livable for who? It’s really important to not lose sight of this as attention shifts. These recent rebellions have necessarily moved outward and became more national, and while of course police brutality and the injustices people are protesting are a nationwide crisis, there is also something specific about what’s happening here in the Midwest.

It matters that some of the places seeing the highest rates of poverty, segregation, and incarceration are in the Midwest. My current book project is around the serial murders of Black women and I started doing that work because nine Black women were murdered in my hometown between 2003 and 2004. What my own research has shown me is that, in the last couple of decades, a disproportionate number of cases of serial murder of Black women have happened in the Midwest. These forms of violence are not one-off things, they’re deeply connected to larger forms of socioeconomic injustice. What is happening in particular to Black communities throughout the region creates the conditions of possibility for what happened to George Floyd, for all of these Black women to be murdered one after another, and for what is talked about as “Black-on-Black crime,” for instance, in a place like the South Side in Chicago. The conditions of possibility for all of these forms of violence are the same: the dispossession of Black communities, the disinvestment from Black communities, and the plunder of the resources of Black communities. What’s important about this moment is to find the through-line and not just talk about the “bad cops” we have to get out of the force or whatever. There has to be more. The mobilizations we’re seeing in Minnesota, as well as across the country, around the necessity of defunding the police and reorganizing resources is attempting to do that work and people are refusing to go back to the status quo. I just hope we don’t lose sight of where it all started.

ANTHOLOGY

Black in the Middle: An Anthology of the Black Midwest

Edited by Terrion Williamson

Belt Publishing

Published September 01, 2020

[ad_2]

Source link