[ad_1]

Ontological evil; the madness of evil or the evil of madness. This is the topic around which Johnny has centered his doctoral degree in Disaster Studies at All Saints University in Manchester, England. Raised in a children’s home, Johnny registers as more psychologically fragile (or maybe just more earnestly human) than the rest of his PhD cohort: Marcie, for instance, the coolly erotic “Den mom” writing on “lumpenproletariat revolt as ultra-politics”; or Gita, whose specialty is queer apocalyptic studies and who, according to Marcie, is “bidding goodbye to heterosexuality by fucking her supervisor.” There is also Valentine, the deicide scholar who wants desperately to be mugged; Ismail, a performance philosopher perpetually “filming the heavens” (and who, as an artist, naturally requires near-constant humbling); and Vortek, who “corresponds with the Unabomber… or says he does,” and everyone agrees “will go on a rampage at some point… A real campus massacre. It’ll probably be part of his PhD—the practical component.”

Of these and their more minor apocalypse-ogling companions, none seem intent on finishing their dissertations. Instead, each is played—not untenderly, though certainly quite successfully—for laughs as they assume positions of unflagging moral superiority to the omnipresent Business Studies Guy, decry “artwank,” and insist that the “revolution really can’t be televised.”

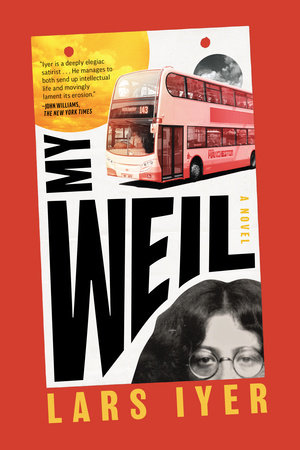

This is the group to which incoming student and fervently born-again martyr Simone Weil introduces herself at the outset of Lars Iyer’s sixth and latest novel, My Weil. Tracing Johnny’s keenly observed, kaleidoscopic field of vision, we bear witness as the student deliberately renamed and assiduously modeled after the philosopher-saint navigates her way through the group’s erratic, lore-ridden world, from the city bus besieged by local alcoholics, or “alkies,” to the Ees, a vaguely zoned wooded area used as both a common space and dump by locals.

Surprisingly, despite her “nun shoes” and “ultra-Christian” demeanor, Simone proves adept at fitting in. It is only when she begins to push past the borders of the PhD cohort’s cynical, circumscribed campus world that the trouble begins. Her attempts to undertake missionary work in struggling parts of the city beget multiple off-page assaults and, eventually, a kind of ambiguous end-of-the-world: a societal collapse whose literal parameters are left open to readers’ interpretation.

The book’s real pleasure lies not so much in any plot or character development but in the sheer incisiveness of its wry, three-pronged critique, aimed at pseudo-intellectual, nihilist, and Do-Gooder frameworks alike. There is an impressive amount of humor here, heaped up in Iyers’ short, periodic sentences. Indeed, some chapters or subsections contain no notable narrative event at all; they simply describe another farce-worthy facet of the overbloated institution and its puffed-up inhabitants, proceeding in prose stilted and italicized to the point of absurdity.

My Weil’s mockery is so scathing that it verges, at times, on numbing. Thankfully, not everything is despoiled. There are genuine exchanges between Johnny and Simone which—though Iyers is careful to handle them lightly—begin to assemble a comprehensive ethic of care:

“When did you know? I ask. When did you know what you had to become?

A few years ago—it doesn’t matter, Simone says.

You felt elected? I ask. A sense of vocation?

I felt called, but I didn’t know how to respond—not at first, Simone says.

And you know now? I ask.

Our hearts can be changed, Johnny, Simone says.

I don’t know what that means, I say.

There’s more than absurdity and meaninglessness, Simone says.

Silence.”

Similarly, the group’s diatribes on academia slip occasionally into elegy, as they describe “revisit[ing] scholarly disputes no one recalls. Affairs of dust. Abstruse debates, figures, names.” They explain how “we’ve wanted to scuba dive around the great wrecks of thought. Among great drowned beasts. Through arching thought-skeletons, picked clean by fishes.” As a result, they have “tasted paradise, Business Studies Guy, and know everything else is bitter,” so that if they “seem to hate everything, it’s only because [they’ve] loved so many things.”

Lines like these perforate already permeable borders between satire and sorrow. In their plaintive defense, they call into question the fundamental value of human toil, thought, and knowledge, exposing an existential doubt which extends well beyond the bounds of institutional academia. At the same time, the book represents a subtler response to aggregate loss and absurdity than its surface cynicism might suggest—intimating, ultimately, that the sum of many disasters might be something akin to meaning.

FICTION

My Weil

By Lars Iyer

Melville House Publishing

Published August 29, 2023

[ad_2]

Source link