[ad_1]

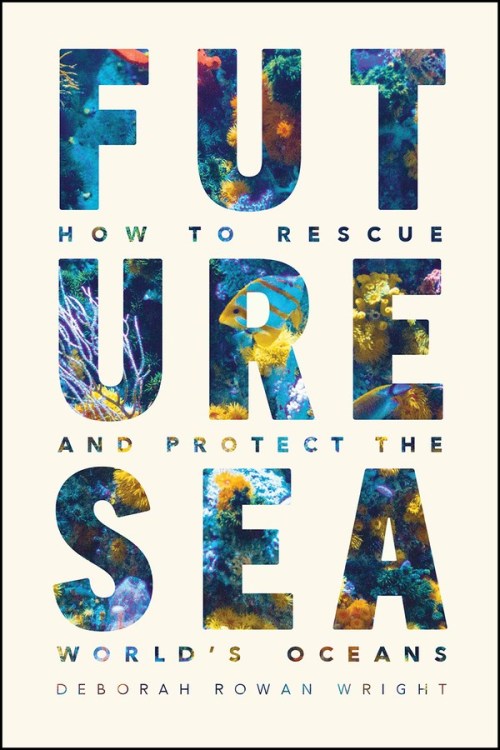

Future Sea: How to Rescue and Protect the World’s Oceans delivers not only the promised “how” but also the reasons why we should safeguard the ocean from human activities. Advocate and researcher Deborah Rowan Wright outlines the critical link between the ocean’s health and our ability to mitigate global warming, the tremendous potential of marine renewable energy, and the ocean’s timeless role as a resource to communities around the world. More profoundly, she argues for its intrinsic value, outside of a human context, noting the vastness and richness of coastal and underwater ecosystems, home to millions of species that are yet unclassified, yet unknown.

While Wright touches on the ways average citizens can use legal systems, technology, and consumer choices to have a positive impact on the fate of the ocean, her central proposal is more ambitious: to upend the default global attitude towards the ocean from a profit-yielding resource to a protected environment with limited and prescribed uses. Our current patchwork of national coastlines, regional seas, and international waters should give way to a concept of the ocean as a single massive system, which should be protected as such, in its entirety. The practical outcome of this adjusted world view would be a global ocean that is entirely protected by law, with fishing, mining, and other exploitative activities being highly regulated. Wright offers examples of successful management of marine protected areas at the local and regional levels, and a convincing legal framework, including the revelation that global protection of the ocean already exists under international law, albeit through legislation that is openly and universally flouted.

Wright also offers a diagnosis of why policy efforts on environmental protection to date have failed, identifying the familiar culprits of outsize industry influence and weak governance. She isn’t afraid to be name names, and they aren’t always the usual suspects. There are the revelations, for example, that in 2006, Iceland single-handedly sabotaged a global agreement to end the massively destructive (and on balance, unproductive) practice of deep-sea trawling. She also notes that there was widespread support for designating ecocide as a crime against humanity that could be prosecuted under international law, until France, the Netherlands, the U.S., and the United Kingdom blocked the initiative. Wright also exposes the challenges inherent in an international system that requires unanimity in decision-making for environmental protection, noting, for example, that the UN division on ocean affairs “conducted working-group discussions for nine years before agreeing that more robust law was needed to protect high seas biodiversity. That was before actual treaty negotiations began. Compare that with how swiftly the bureaucratic machinery of war can kick in — within days or even hours.”

The meticulous focus on international policy — its history in relation to the ocean, events afoot and ways to speed the process — can at times take a wonky turn. The progression of information is curiously inverted in complexity, with the first half of the book apparently directed to those with some knowledge of the issues, and the second half pitched at the beginner’s level. Codification of customary law in treaties, for example, is referenced casually in the second chapter, while customary law itself is explained in simple terms in the sixth. The first half of the book also slips into an overreliance on acronyms (a common pitfall of the technocrat), which make the average reader glaze over or lose the thread (My favorite of the many acronyms is BOFFFFs, for “big old fat and fecund female fish”). The early technical chapters thus require some perseverance, yet it’s clear this is not a book entirely for “stakeholders”: The second half, for example, lays out the various arguments and solutions in clearer language, and includes a chapter dedicated exclusively to the average consumer and the small changes anyone can make to reduce their toxic impact.

The times when Wright draws on her own experiences with ocean life and researching her subjects are when the language is liveliest. Her arguments are most convincing when her own voice is clearest — when the frustration, passion and will for change of an individual emanate in a kind of slow-burning glow of articulate British restraint. The voice of a single rational, concerned woman make the bolder claims and proposals all the more stealthily convincing. She characterizes the U.S. as being an oligarchy rather than a democracy, for example, and makes a fierce case against consumerist culture, including its demands for sparkling cleanliness and constant chemical maintenance of all domains, from home, to clothes, body, hair, and skin.

While the book is rich in positive examples, it doesn’t constitute a simple case for optimism. In the process of laying out solutions, Wright reveals the extent of the problems. Mass-scale plastic pollution, deep-sea mining, coral bleaching, purse seine fishing, and toxic fish farming are just some of the distressing issues detailed, and even those bravely trying to stay aware of the state of our environment may discover fresh horrors. Wright is aware of how hard it is to take it all in: “Bad news comes to us constantly, like a nagging little demon on our shoulder, bringing us down, sapping our optimism, and lowering our spirits. It can suck out the energy needed to make change happen.” But it is her sensitivity to both the complex emotional response to environmental destruction and the profound connections human beings have to the natural world that make the book an effective advocacy tool. I certainly didn’t feel emotionally prepared to take in more environmental “bad news,” but found myself changed after reading the book, feeling that understanding, bearing witness, is also part of making a change. The trick is to move past the paralysis. Wright pinpoints what is perhaps the greatest challenge, our current global leadership vacuum, describing her dream of “leaders with compassion and integrity.” The implicit message is that for good leadership, too, we all bear some responsibility.

NON-FICTION

Future Sea: How to Rescue and Protect the World’s Oceans

By Deborah Rowan Wright

University of Chicago Press

Published October 27, 2020

[ad_2]

Source link